Indigenous artist’s painting on museum rooftop to be visible from the Eiffel Tower

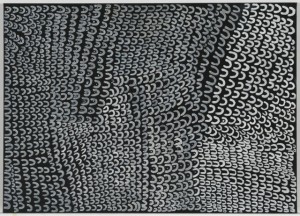

Dayiwul Lirlmim, by Lena Nyadbi. To be painted onto the rooftop of the musee du Quai Branly in Paris.

Sydney: One June 6 this year (2013), a black and white painting by the senior indigenous Australian artist Lena Nyadbi will be unveiled in Paris. Uniquely, the painting will be on the rooftop of award-winning architect Jean Nouvel’s museum of the world’s “first peoples”, the musee du Quai Branly, located on the banks of the Seine in central Paris.

Nyadbi’s work — enlarged 46 times from its original size — will be visible not from the museum itself, but from the iconic Eiffel Tower in whose shadow the musee du Quai Branly stands.

Lena Nyadbi is a Gija woman from Warmun, in the Kimberley region of Western Australia.

Thought to be in her 80s, Nyadbi radiated a large amount of quiet goodwill and gentle pride when she attended the official announcement of her commission in Canberra on April 29, 2013. The ceremony was at the National Gallery of Australia.

Stephane Martin, president of the musee du quai Branly, was at the announcement. So was the Australian businessman Harold Mitchell, whose Harold Mitchell Foundation paid $500,000 for the commission to be realised.

“It’s the first time a museum has commissioned a piece that will not be visible from the museum. You have to be outside the museum to appreciate it,” M. Martin told me in Canberra.

A committee of people, including former Art Gallery of NSW indigenous art curator Hetti Perkins, recommended Nyadbi’s work for the rooftop project. In particular, it was her canvas Dayiwul Lirlmim (which translates as Barramundi Dreaming) that won the commission. A section of that original painting has been chosen for reproduction directly onto the rooftop of the musee du Quai Branly.

A committee of people, including former Art Gallery of NSW indigenous art curator Hetti Perkins, recommended Nyadbi’s work for the rooftop project. In particular, it was her canvas Dayiwul Lirlmim (which translates as Barramundi Dreaming) that won the commission. A section of that original painting has been chosen for reproduction directly onto the rooftop of the musee du Quai Branly.

While the original painting was completed in ochres taken directly from the earth of Nyadbi’s homelands, the reproduction on the rooftop will be completed in rubberised paints like the paints used to mark traffic directions on the streets of Paris.

M. Martin anticipates the painting will have to be renewed every 15 years or so, owing to degradation caused by the rain, snow and sunshine of Paris.

The idea of commissioning an artwork for the rooftop came from the architect Nouvel.

“Nouvel was thinking about what he called the fifth façade for the building. That was the starting point. Why would not we discuss a commission for a new indigenous art painting?” M. Martin told me.

Workers will use one-metre square heavy paper stencils to transfer Nyadbi’s work onto the rooftop. The stencil designs have been digitised so the stencils can be re-manufactured on requirement — “as long as we don’t lose the disc, which we are very good at, usually”, M. Martin laughed.

He added that the musee will have a webcam installed on the Eiffel Tower so that people worldwide can observe the painting through different seasons.

“The Eiffel Tower is just above the museum,” he said.

I asked M. Martin why indigenous art had been so willingly embraced by Parisians.

“I don’t know why. There’s a strong connection between France and indigenous Australian art. We still acquire new artists as much as we can and the response of the audience is very good,” he said.

“I don’t know why. There’s a strong connection between France and indigenous Australian art. We still acquire new artists as much as we can and the response of the audience is very good,” he said.

The musee du Quai Branly receives 1.3 million visitors a year. But seven million people will see Nyadbi’s rooftop artwork. That’s the number of people who travel to the top of the Eiffel Tower every year.

Jonathan Kimberley, manager of the Warmun Art Centre, said the Nyadbi commission’s significance should not be understated.

“I think it’s highly significant for contemporary art, world wide,” Kimberley said “I can’t think of any similar installation into the very fabric of a city. It goes beyond just Australia. Interest in France has been steadily growing. We really congratulate the musee and the city of Paris for its vision to include such a work in such a prominent location. It’s a very powerful statement.”

Naturally, a contingent from Warmun will travel to Paris for the opening of Nyadbi’s commission, including the artist herself if her health permits it.

But there will be another celebration awaiting the group when it returns to Warmun. In 2011, a flood destroyed the Warmun comunity and the arts centre. Hundreds of paintings, according to Jonathan Kimberley, were washed away.

Luckily, however, the community’s collection of historic Warmun paintings — almost 400 of them dating back to the 1970s — were kept separately to the more recent works and survived the flood. The historic works were, however, water damaged. They have been undergoing restitution work at the Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation in Melbourne.

“They have done a brilliant job of bringing the collection back from the brink,” Kimberley said.

“It’s one of the most significant collections documenting the origins of an indigenous art movement in Australia.”

The art centre has also been renovated.

An “intercultural education program” between Warmun Art Centre and the University of Melbourne is now being established, Mr Kimberley said.

Warmun lies at the centre of Gija country, which extends for 100km in every direction from the community.

When Nyadbi paints, she uses natural ochres and charcoal found in the local landscape.

“Most people don’t get the significance. It’s literally part of the country,” Kimberley said.

When I got the chance to meet Nyadbi, I asked her whether she would take the lift to the top of the Eiffel Tower and look down on her artwork. She giggled.

“I’m not going to get up there! Too high! White people can go up there,” Nyadbi told me.

Lee-Ann Buckskin, chair of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art board of the Australia Council for the Arts, said Nyadbi had “transformed the way Aboriginal poeple see themselves contributing to the global art community”.

“Without our art we have no connection to our land. It maps important details,” Buckskin said.

She said Nyadbi’s installation would “change the Paris landscape forever”.

Here is a link to my story about Lena Nyadbi and the Musee du quai Branly in The Art Newspaper.

Elizabeth Fortescue, May 26, 2013

Addendum:

I wrote to Stephane Martin after meeting him in Canberra and posed some questions to him about the Lena Nyadbi commission.

Here are the questions, and M. Martin’s responses.

Artwriter: Has the musee du Quai Branly established any special ties or relationships with particular Australian art galleries or arts bodies while in the process of negotiating the Lena Nyadbi project? If so, which ones?

Stephane Martin: Since the beginning of this project, the musée du quai Branly collaborates closely with the Australia Council for the Arts. They helped us significantly in its concretization. This project also received the support of the Harold Mitchell Foundation. Harold Mitchell acquired Lena Nyadbi’s painting and will generously donate it to the musée du quai Branly. This project had been accompanied by the Australian Embassy in Paris and the French Embassy in Canberra.

Finally, I was also very pleased that the Australian launch was welcomed at the National Gallery [of Australia].

Artwriter: Are any future projects or exchanges planned between the musee du Quai Branly and Australian institutions? If so, can you provide any details?

Stephane Martin: Since its opening, the musée du quai Branly cooperates and forged links with Australia. Several projects have been led with Australian Institutions. For example, from October 9th 2012 to January 20th 2013, the musée du quai Branly presented an exhibition titled “The origins of Western desert aboriginal Art – Australia – Tjukurrtjanu”. This exhibition, organized in collaboration with the National Gallery of Victoria and Museum Victoria, and in partnership with Papunya Tula Artists, displayed 160 pictorial artworks and 70 objects presented for the first time in Europe.

By the moment, the following projects are in progress with Australian Institution at the musée du quai Branly:

Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islands Curators residential program:

On November 2nd 2011, the musée du quai Branly and the Australia Council for the Arts signed a memorandum of understanding to develop and coordinate a curators’ residential program for 3 years. This cooperation aims at devising and supporting projects with the goal of furthering understanding and knowledge of historical collections, and broadening international networks as well as furthering the promotion of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islands art and culture. In addition to this project provides an opportunity for curators from Australia to work with the curatorial staff at the musée du quai Branly. At this occasion, Mrs Alisa Duff, Head, Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander program at the National Museum of Australia, spent 6 weeks at the musée du quai Branly from October 15th to November 28th 2012, with the financial support of the Harold Mitchell Foundation. In return, Mrs. Magali Melandri, Head of Oceania collection at the musée du quai Branly, will be welcomed at the National Museum in Canberra this summer during 4 weeks.

Aboriginal Visual Histories (2011 – 2015):

From 2011 to 2015, the musée du quai Branly in cooperation with the Monash University in Australia, the museum of archaology and anthropology of the University of Cambridge (GB), and with the National Museum of Ethnology (Leiden NL) conduct a scientific research on the Aboriginal visual collections in Europe dating from mid 19e century to the present days. This project main goal is to a better understanding of the photographic collections of Australian Aboriginals and promotes the sharing with the descendants of Aboriginal people. The musée du quai Branly focuses it research on its collection of photographs taken by Desiré Charnay during his expedition in Australia.

Finally, the musée du quai Branly wishes to increase its Australian Aboriginal contemporary art collection. The musée du quai Branly conserves around 33 000 objects from Oceania including 1423 aboriginal art objects from Australia such as weapons, boomerangs, 250 bark paintings from Arnhem Land and 69 Australian Aboriginal contemporary paintings.

Artwriter: The banks of the Seine and the deserts of Australia are about as distant as it is possible to get. Why are the French people so interested in Australian indigenous art that they would like to install it on the rooftop of a museum in central Paris?

The musée du quai Branly is not only a museum that displays an ethnographic collection but also carries the ambition of being an original place displaying a different vision of Non-Western cultures. The musée du quai Branly proposes to show off, to the visitors, new horizons essential to oneself understanding. The musée du quai Branly does not display objects from Europe, but presents cultures from Oceania, Africa, Asia and the Americas. The Australian Aboriginal contemporary art collection holds a special place at the musée du quai Branly. It is possibly the most important collection in Europe, which has been constituted in the late 80’s, early 90’s by the curators of the Musée National des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie.

Furthermore, the musée du quai Branly presents Australian Aboriginal contemporary art in a permanent way. The Australian Indigenous Art Commission at the musée du quai Branly, which was launched in the early 2000s, is one of the most significant cultural projects for Indigenous art from Australia in France. The installation of eight artists John Mawurndjul, Paddy Nyunkuny Bedford, Judy Watson, Michael Riley Gulumbu Yunupingu, Tommy Watson, Ningura Napurrula and Lena Nyadbi are engraved in one of the musée du quai Branly’s buildings located rue de l’Université, and are very popular to the public. This project has been highly supported and accompanied by the Australian Government, the Australia Council for the Arts and the Harold Mitchell Foundation. The success of this project which is a landmark event for contemporary Indigenous art from Australia, explains my wish to renew this experience with the Lena Nyadbi’s installation on the musée du quai Branly’s rooftop.

With best regards,

Stéphane Martin

| Print article | This entry was posted by Elizabeth Fortescue on May 26, 2013 at 9:57 pm, and is filed under News. Follow any responses to this post through RSS 2.0. You can leave a response or trackback from your own site. |