News

Song Dong and Waste Not: the artist and his work

Dec 29th

A few weeks ago, Chinese artist Song Dong arrived in Sydney prior to installing his Waste Not project in Carriageworks, Eveleigh, as part of the Sydney Festival 2013. He was also preparing for his wider exhibition at the 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art in Sydney. I met the artist shortly after he arrived at Carriageworks, and had many questions concerning what I thought was a fascinating project.

A few weeks ago, Chinese artist Song Dong arrived in Sydney prior to installing his Waste Not project in Carriageworks, Eveleigh, as part of the Sydney Festival 2013. He was also preparing for his wider exhibition at the 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art in Sydney. I met the artist shortly after he arrived at Carriageworks, and had many questions concerning what I thought was a fascinating project.

Song Dong turned out to be a quiet and self-effacing person. But he was also engaging, and very keen to discuss the intricacies of the project.

A short preamble: Waste Not (or Wu Jin Qi Yong in Chinese) is a remarkable artwork which constitutes an actual bedroom and living area of his mother’s tiny Beijing home as well as more than 10,000 individual domestic objects which she kept, some of them for up to 50 years.

The modest little home still exists, minus the small section which was demolished because it failed to reach safety standards. The house is in Banshang Hutong, a tiny street where traditional daily life still bustles on virtually in the shadow of “new” Beijing’s high-rises.

Waste Not includes chairs and tables (some broken), fabrics, two old beds, wardrobes full of second hand clothes, hundreds of kitchen utensils from mis-matched sets, hundreds of old shoes, toys, electrical wires, enamel basins, plastic buckets, string, old magazines, lamps, clocks, telephones, record players, empty toothpaste tubes, bottles, bottle caps, fast food containers, hard soap bars, shopping bags, moon cake boxes, tea boxes, yarn, radiators, blankets, bird cages, old television sets.

Song Dong’s mother, Zhao Xiangyuan, saved all these things from the 1950s to 2005. To understand why, you need to know her story.

Zhao Xiangyuan was born in 1938 in Taoyuan, Hunan province into a prosperous family. But in 1953, her father was declared a spy. He was arrested and jailed. The family’s circumstances changed dramatically.

Zhao Xiangyuan and her mother struggled. They lived in a tiny home in hardship and poverty. Zhao Xiangyuan sewed buttonholes and glued paper bags for department stores.

Zhao Xiangyuan married, and her son Song Dong was born in 1966. Life was hard, and the young family lived in a single room. Zhao Xiangyuan began to hoard items like soap, which was rationed.

In 2002, Zhao Xiangyuan’s husband Shiping died suddenly. After that, she couldn’t bear to part with objects which reminded her of her past domestic life.

The life of privation which gave rise to the Chinese proverb “waste not” affected an entire generation, but is little understood by the young people of modern China, for whom consumerism and commerce are a way of life.

After Zhao Xiangyuan suffered a nervous breakdown and refused to part with any of her hoarded objects, Song Dong devised a way of helping her out of her silent grief. He decided he would create an artwork in which his mother would be the true artist and he would be her assistant. That work was Waste Not. He would rebuild a corner of his mother’s home and offer her the chance to sort through all her belongings. He called it “organising her memories”. As she sorted, she discussed all the items and their histories. Finally, the sorted items were exhibited for the first time in 2005 in Beijing.

At that time, Song Dong’s mother said to him: “You see that keeping [all the objects] was useful!”

When the work was put on show, Zhao Xiangyuan was on hand to discuss her life with visitors. The older ones among them would have identified completely with her frugality, having also lived through hard years when no one ever threw anything away. Anything, they would say, could come in useful some day. Discussing all these things brought Zhao Xiangyuan out of her shell. It had exactly the effect for which Song Dong had hoped.

The artwork became a true family affair. Song Dong’s sister Song Hui is also involved, and was there the day I interviewed her brother at Carriageworks. She is the project archivist.

Song Dong’s wife Yin Xiuzhen (an artist) and their daughter Song Errui (aged 10) were due to arrive the following week to work on the installation of the work. Song Dong told me that he talks to his daughter about the objects as they arrange them together, so she learns about her family history that way.

Zhao Xiangyuan, sadly, is not able to help with the Sydney presentation of the project. She died in January 2009. Her family, however, is carrying on without her. I have read an interview in which Song Dong declares that his mother was the one who deserved the prize which the work won at the Gwangju Biennale, because “she has used her entire life to create this work”.

Waste Not has already been seen in New York, Korea, Germany, England and Berlin.

Here is my interview with Song Dong, carried out on December 13, 2012.

Song Dong: This is a part of our home. We have six rooms but this is two rooms. Our family moved many places. In China we can’t have our real own house. This is a very traditional (house).

He said the house would be more than a century old and many families would have inhabited it.

We rented the house. Every house belong to the government. Now we can buy the home. But only the house, the land is the government’s. My mother also lived inside, for two or three years. Because the government said too old, very dangerous. You should take down. So I built the new house there but my mother said don’t throw away anything. I said where I can put? She said you can use them to build a new house because the wood is still good.

Since 2002 my father suddenly passed away. My mother silent. Just cry. Don’t talk with other people. I can’t do. I can’t help her. So I send my mother to the south of China with my sister while we organised her home. We think she happy with organised home but she was really angry. Why do you throw my things away? The whole night I can’t sleep. I asked her why [did she get angry]. She said your father is gone. I afraid of empty room. I need the object to fill and cover memory so I can feel your father still there. That really touched me. I thought I will give my mother a job. Let her organise things. I said we will keep all of them. The job is to put the same thing together. For example the shoes. I want her to know how many shoes you have. How many things you have.

His mother had misgivings that people would think she was messy, but her son encouraged her.

I said when we show this work, I will be famous. Because before I did a lot of work with my father. It will be shown in 4A. All the work is working with my family. Because they can do everything for me.

Now I am really sad to throw away. [He wishes he hadn’t thrown away a lot of old used tea-leaves, which his mother used to keep in case she wanted to stuff a pillow with them].

That’s the old generation. But the young generation they throw away anything. They just want to use everything now. Mobile phone. The whole society wastes a lot. It’s not a good thing for our life. This project shows people to think what can we use again.

His mother died in 2009.

This project is not a still show. It’s a develop show. When my mother alive I work with her each time doing the exhibition and she note down a lot of the story of each [object]. We make the archive.

In the beginning it was really hard for my family. I cry every day.

In that work, my mother and father never pass away. I think they are living in art.

Each time [the work is installed] is different because I will reshape the space. [There are parts for the parents, the grandparents and his own children.]

My wife also artist. She help us to do the image archive. One by one every object will take the photo. Maybe in the future we will make a website of it.

I looked up about the Beijing hutongs on-line, and found they are the historic heart of Beijing. They are higgledy piggledy little lanes and alleys, full of old charm. From the sky, they are an unbroken plateau of tiny rooftops. They are under threat of redevelopment, but those who fight for the hutongs are very passionate about them, describing them as the culture of Beijing itself.

After my interview with Song Dong, I noticed this poster on a pole outside Carriageworks. The story continues.

Elizabeth Fortescue, December 29, 2012

Sculpture by the Sea 2012: a Bondi experience

Oct 23rd

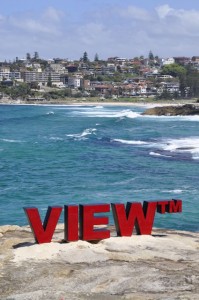

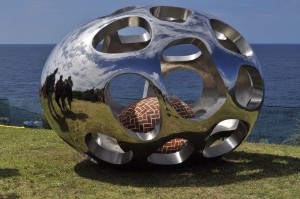

This fabulous artwork by Dave Mercer (left) is one of the stand-outs at this year’s Sculpture by the Sea, Bondi. “It often seems that even the most basic of human experiences need to be branded in order to seem important and valid,” the artist writes in the SxS catalogue.

This fabulous artwork by Dave Mercer (left) is one of the stand-outs at this year’s Sculpture by the Sea, Bondi. “It often seems that even the most basic of human experiences need to be branded in order to seem important and valid,” the artist writes in the SxS catalogue.

The work, in powder coated stainless steel and acrylic, pulses in bright, vivid red on the cliff-top overlooking the ocean at the Tamarama end of the sculpture walk.

Here is a selection of pictures I snapped at the media preview for Sculpture by the Sea last week. Hover the mouse over each picture to see the artist’s name and the title of the work.

Elizabeth Fortescue, October 23, 2012

Bernard Ollis: an artist’s insight

Sep 11th

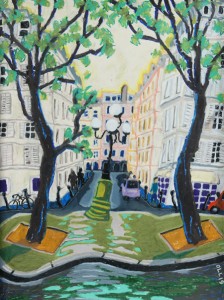

Bernard Ollis‘s latest exhibition, Paris Considered, was recently on show at NG Art Gallery in Chippendale. I had the pleasure of opening the exhibition.

Bernard Ollis‘s latest exhibition, Paris Considered, was recently on show at NG Art Gallery in Chippendale. I had the pleasure of opening the exhibition.

I thought the time was ripe to post a transcript of my first ever interview with Bernard. There have been many since then, and Bernard and I have become firm friends. But during that first interview on June 6, 2006, there was a lot to ask Bernard because we had never met before, or if we had, it was only briefly. We spoke about his exhibition, The St Peters Suite.

Here we go, starting with Bernard.

Bernard: I’ve titled [the exhibition] The St Peters Suite by virtue of the fact that these paintings were done in this wonderful big studio [the studio he still occupies in St Peters with Wendy Sharpe] and that’s given me an opportunity to put lots of things up at the same time, and you can make comparisons which you can’t do if you’ve got a smaller space. It’s probably helped [the exhibition] to be a little more thematic than it would have been.

We [Bernard and Wendy] moved into the studio approximately four years ago. I never dreamed I would be able to work [in such a big space]. It’s also exciting to bring people in. It’s an empowering thing that people can come in and see lots of work and realise that you’re not just fiddling around the edges — it’s real!

Artwriter: You work a lot in the studio?

I’ve always been very disciplined. I also have the ability which I’ve learned to do over the years to be able to switch on and switch off. In order to keep going as an artist I can’t bring my job home with me. I can put on my favourite classical music and immediately get into a mood where I can pick up the pieces and start working again.

That’s something I think I probably developed. Because if I couldn’t do that it would be out of kilter. For me, in order to be a good director of the art school, I need to be a painter and working on ideas. Everything gives confidence to everything else. It’s the only ying and yang thing. You balance your life. [At this time, Bernard was director of the National Art School, Sydney.]

When you come in to the studio, is it like an oasis?

Yes. I usually switch the mobile phone off and put some music on and in a very short space of time I feel very much at home. Because I’ve got all these works around me I immediately step into their world. [It’s] like Alice Through the Looking Glass — I actually step into the paintings and I’m suddenly confronting and thinking about …. it’s a sort of pictorial world I can enter relatively easily and find solace or stimulus.

I don’t like to be too obvious or literal whenever I paint. I’m not an illustrator. I’ve always wanted to be one step removed. I don’t just want to paint pictures of me and Wendy. So I’ll change my character or my personality or the male or the female role and turn them into other people. I suppose it’s a little bit like the world of theatre where I did some paintings previously to do with masks and changing your personality and stepping on to a stage where you’re actually somebody else. They’re sort of like penultimate moments. They’re open-ended. They are a narrative and allegory of people’s lives and metaphors for things. A lot of them feel like they’re on some sort of stage. The stage can be indoor or outdoor, and sometimes we don’t know which way round it is at all. So I’ve put people in positions which are confronting to them, or they’re just getting on with their lives or they’re standing looking back at us. I’m not an angst painter. I often have people with somewhat more anonymous or pondering faces. I don’t want it to be like ‘I am happy, I am sad or I am angry’. I want the viewer to step in.

This one [he showed me a picture of people in a hotel room], there is a story behind it. I did a drawing when I went to Sri Lanka and the drawing was of this amazing room we were staying in. When we came back, about eight months later, that’s where the tsunami went through. This hotel was a little ground floor place in probably the lowest part of the town. We said, ‘that place wouldn’t exist anymore’. It would have filled up like a sink.

I remember the place and the woman who managed it and all those sorts of things. I came in and I painted that. I did it from the drawing, which was not necessarily a pessimistic drawing. It’s a sort of premonition or a thought. But it’s not important to know that to gain something from the painting.

For you it’s almost like memorialising the people who might have been in the room?

That’s right.

You look down on the room from an odd perspective, as though you were above the actual ceiling fan.

I’ve always been interested in multi viewpoints. I try to turn the ordinary into the extraordinary. I try to put in a number of angles, and I think it just makes it more powerful. It’s a more powerful way of entering into the space than the normal horizon line. I like that idea of being in a number of vantage points, or disappearing off the bottom edge.

Could you tell me about the use of dogs in your work?

Could you tell me about the use of dogs in your work?

I have a slight apprehension of dogs, but like all humans I see them as wonderful creatures and in the ideal world if I wasn’t travelling so much, I’d have a dog. As a child I loved that sort of thing. There was a nasty story where a dog mauled my dog and it only lived a few weeks afterwards and I had about 37 stitches in my hand. The worst thing was this dog was completely mad and just ripped my dog apart. I won’t go into details. I was about 12 or 13. And I came home carrying my little cocker spaniel and I knocked on the door, my hands were bleeding, and my poor mother came to the door and almost fainted. It was a traumatic thing, very traumatic at the time. You know they say dogs can sense fear. Sometimes I’m walking down …. And I’ll just have a déjà vu and I just think I don’t trust it 100 per cent. There’s just that slight thing. But these pictures of dogs are probably a celebration of the way people take dogs out to parks and go places and do things.

All your dog pictures look happy (except perhaps the one at left).

Yes. So I’m not setting out to create that worry or whatever. But I suppose I’m drawn to looking at them and dealing with them.

It’s to do with anger and aggression. I suppose deep down I hate anger and confrontation. I think civilised people should do. But I’ve always walked away from any situations. I’ve always thought the idea of a human hitting another or any of those angry things, I just feel quite sickened by. I suppose I’m instinctively a pacifist on all levels. First and foremost, above all my political things, I describe myself as a pacifist. Dogs are metaphors for different breeds of people and attitudes people have.

The painting of the man and woman dining with a sinister character in the background. And the midnight band painting (at left)?

The painting of the man and woman dining with a sinister character in the background. And the midnight band painting (at left)?

I like that mood, and I like that sense of melanchony or unsure. But the one where the two people sat by the dinner painting. What’s nice is I go on a journey myself when I paint them. They’re not totally worked out. So I had two people sat there at a table and I thought, wouldn’t it be interesting to put them in a very unusual environment? The background now is they’re on the end of a road and there’s this other figure, I don’t know who he is, and he’s walking in and seeing the situation. Within that ménage a trios I’m setting up the situation: should he be having dinner with her? What’s going on? It’s a lonely space, and you assume you could hear the footsteps. You put those ingredients together and depending on your mood could go into any direction whatever. And I change things as I go along. (He might open the eyes of one person, or change their expression.) I had a couple of figures looking through the window but I thought it was adding too much to the set. I genuinely don’t know the answer (to what they all mean.)

If you think of my work as all about humanity and how people interact or don’t interact then you’ve got a situation in which he might be the hero, she might be the villain. It’s a slightly threatening mood, but one might say it’s just a clear still night and the pathway is like a journey from one place to another. There’s a lot of theatre. Most of these paintings are travelling somewhere. They’re going somewhere.

What do you read?

I read quite a lot when I get time. It’s a wide range. There’s no definitive thing. I’m even reading Dickens again. From Dostoevsky to Dickens and The Little Seamstress. I like French cinema because it’s to do with the psychology of people; confrontations or affairs, and guilt, and fear, and other aspects which are deeply laden in all of us and we all try to suppress. I try to play some of those things out.

Were your parents arty?

No, not at all. There were no paintings on the walls and very few books. I really do come from a working class family. Council estate. And I was an only child. My father was a sporting person and he worked at the gas board. My mother cleaned floors. [Going to school, Bernard would walk past the grand Georgian houses and the house where Jane Austen lived, and was fascinated and took it in subliminally.]

What opened art and literature for you?

When I was 10 or 11 years of age I got a record player and everybody was going out and getting The Beatles or The Stones, and I was interested in that, but I was also interested in Tschkaikovsky and Stravinsky. I listened to radio programs and found orchestral music to be a rich source; I found I could listen to it longer and further, whereas (pop tunes were soon boring.) That probably got me into reading books and other things. I left school at 16. I worked for over a year. When I was about 18 and I went to art school, my mum and dad said if you want to do it, do it, and I didn’t know what the end product would be. I went to Cardiff College of Art and I took a big truck and my dad drove the truck and it was full of art, sculpture and all sorts of things, and I remember them saying have you got a folio – and they expected me to have a little thing you open up with five or six pieces of work – and I started opening the truck and friends of mine started pulling things out and they said ‘stop, stop, you’re in, you’re obviously a natural’.

I was working doing post office and different jobs to keep going. But there were grants. Because I was working class you could get a grant so I had just enough and I would work at weekends. I did four years at Cardiff, then I went to the Royal College of Art. There were 800 applications and they took 20, at that wonderful time when people like David Hockney, RB Kitaj and Peter Blake and a lot of really significant artists were there doing a day a week. It was very very exciting and I did 3 years at the RCA. At the end I remember a professor asking what I thought about the course, and I said I wish the course was longer. I just want to keep going. So I’m lucky because I can’t think of doing anything other than making art.

I came to Australia in 1976. I came from London to Darwin in one move. Got a job in Darwin Community College. I did it for a bit of experience. I was 25 and I got a job as a lecturer but I didn’t realise quite what an isolated community it was. And it was only a year after the cyclone and there was hardly anything left standing. I don’t think anybody else applied for it! I stayed in a caravan in a swamp with power cuts all the time and I started to teach art in this isolated community and I thought if I did a good job I would be recognised in other parts of the country, but nothing could be further from the truth. I was in Darwin three or four years, but travelled extensively. Started to show in Sydney and Melbourne. I started to realise that Australia was a very exciting place. I enjoyed very much the lack of snobbery. Being working class was now no longer a handicap.

Next moved to Bendigo, working in the art school at Latrobe Uni and going to Melbourne quite a bit. Came to Sydney in 1996 as head of painting at the National Art School and soon got job as director in 1997. I do enjoy steering the art school in a direction which would be good for this city and country. I feel like a custodian, and it’s a very exciting place to work.

Elizabeth Fortescue, September 11, 2012

Double Take: new exhibition at White Rabbit Gallery

Aug 31st

I took these pictures at the installation of White Rabbit Gallery‘s new exhibition, Double Take, which opens tonight.

I was lucky enough to interview the Taiwanese artist Tu Wei-cheng about his work Happy Valentine’s Day, which is pictured below. My story on this artist appeared in the Daily Telegraph.

Some of the pictures are of Dust, an installation by artist Cong Lingqui who meticulously created tiny repilcas of 210 everyday objects which the installers were suspending from the ceiling while I was there.

Here are my pictures.

Elizabeth Fortescue, August 31, 2012

Adam Cullen, 1965-2012

Aug 11th

I’d like to report on Adam Cullen’s funeral, as well as the last time I saw him alive, before the memories start to fade inevitably from my mind.

The funeral was held at 2pm on Friday August 3, 2012, at a modest suburban church call St Rose, in Collaroy Plateau on Sydney’s northern beaches. Right opposite the church was Wheeler Heights Primary School, where Cullen had attended school as a child. When I arrived at the church, pop music was pumping out into the playground and dozens of kids were practising some kind of dance routine.

As I stood opposite the church, I observed Cullen’s father, Kevin, arrive. I wondered how he must feel, about to say a last goodbye to his child. I noticed several motherly-looking women heading for the church hall, bearing plates of food covered with tea-towels. It turned out they were taking the food to the church hall, where we would gather later and eat sausage rolls and lovely little sandwiches and cakes. There was a smattering of younger people at the funeral, but the congregation seemed mainly to be late middle-aged. They looked like nice, hard-working folk, probably the sort that surrounded Cullen as he grew up on the northern beaches and went to school at Cromer High.

At 2pm I crossed the road and entered the church, and sat at the side from where I saw Adam’s simple wooden coffin. It was heaped high with a beautiful display of native flowers. Next to the coffin was one of Cullen’s artworks. It showed a dog with a big, dopey grin, tongue lolling out, eyes swivelled to one side. Another nice touch was the order of service, all done in bright pink and featuring some of Cullen’s paintings.

The eulogy was given by Charles Waterstreet, the well-known Sydney barrister who writes for the Sunday Telegraph. Cullen had once told me it was Waterstreet who kept him out of jail. I thought he was exaggerating but, as I was to find out while covering Cullen’s court appearance on firearms and drink-driving charges, it was no exaggeration at all.

A transcript of Waterstreet’s eulogy is here.

The service was a full Mass. It was moving without being sentimental, and it was hard to believe that one of the Sydney art world’s great rebels was being farewelled amid such middle-suburban propriety and quiet goodwill.

Some of Cullen’s portrait subjects were in attendance. There was actor David Wenham, whose portrait in Dulux house paints won Cullen the 2000 Archibald Prize. Comedian Mikey Robins was there, overcome with grief. Artists who attended the funeral included Peter Kingston who told me he had come to pay his respects although he had never met Cullen. Kingston said he had heard of Cullen’s precarious state of health and had written him a letter expressing his admiration for Cullen’s work. Kingston had posted the letter on the Friday, but Cullen would not have received it. He died that weekend. I wondered who ended up opening that letter, and what emotions would have occupied them as they read Kingston’s no doubt very tender and honest words. Nigel Milsom, who painted Cullen for the Archibald, was there. So was another Archibald regular, Rodney Pople. Cullen’s dealer, Michael Reid, was also there. Artist Adam James K., who painted Cullen’s portrait and was a very close friend, was there.

Andre de Borde was there, also grief-stricken. De Borde had co-curated Cullen’s extraordinary exhibition in September 2011 at Chalk Horse Gallery in Surry Hills, called Independent Judiciary (Mother’s Milk). And art gallery owner Jason Martin, possibly Cullen’s oldest friend, was there. He and Cullen had met on the day they were both brought with their mothers to start school at Wheeler Heights Primary School. Neither of them had wanted to go to school, and they became friends on that very first day. Martin told me his mother has a very clear memory of that first school day. Adam Cullen’s friendship with Jason Martin endured right to the end. In the days before Cullen’s death, Martin had stayed with him at Wentworth Falls and, like boys again, they had watched movies on TV. Being There with Peter Sellars, and “a really trashy film about a snow monster”, Martin said.

Martin said Cullen had lived how he had wanted to live, and “it was precarious”. “He had more than nine lives, I can tell you that,” he told me in the church hall after the service. “And he kept his sense of humour right up till the end.”

One of the most touching things about the funeral was the tribute by the children of Wheeler Heights Primary. The kids had always wanted Cullen to visit their school and talk to them about his art, but it was not to be. After his death, they produced an entire wall full of their drawings based on his Ned Kelly pictures. They made a perfect backdrop at the church hall where the army of nice ladies offered platters laden with tasty food.

And now Cullen is gone, aged just 46. It is believed his ashes will be scattered in the surf at Collaroy Beach where his mother Carmel’s ashes were scattered two years ago.

Addendum: The exhibition Independent Judiciary (Mother’s Milk), curated by Andre de Borde and Jasper Knight, was a departure for Cullen. He had created a series of paintings made in a highly unusual way. Cullen claimed he was the first Australian artist to do it. He had gone to the country, and set up his canvases behind spray cans of paint. He shot bullets through the spray cans, and they spun like Catherine wheels, spitting paint in all directions including at the canvas. Of course the bullets went through the canvases as well, and became part of the works. I had gone to Cullen’s Blue Mountains studio to interview him about these works, and my story was used in the Daily Telegraph.

The next time I saw the artist, on November 10, 2011, it was in court number 4.5 in the Downing Centre. I was there to report on the case for the Daily Telegraph. Immediately after Cullen had made the artworks with bullets and spraycans, he’d been pulled over by the police and charges were laid relating to drink-driving at an alcohol concentration of 0.132, and the cache of weapons that was in his car, some of which were unlawfully in his possession.

For his day in court, Cullen looked dapper in a western-style outfit with a cloth cap, and shoes that were splashed with paint. One of his hands was in some kind of support, as though he had injured himself.

Looking around the waiting area outside the court, he noticed that there was “carpet on the walls”. I remarked to Cullen that the carpet was probably to absorb the noise. He replied that it was “probably to absorb the anxiety”. He was nervous, and understandably so. Depending on the outcome of the case, he could have been about to go to jail.

Cullen arrived outside the court alone, but he was soon joined by a small group of supporters including his cousin, the photographer Murray Vanderveer, and the artist Jasper Knight.

Inside the court, he held his cap in both hands, looking for all the world like Toad of Toad Hall promising the magistrate he would no longer roar around in his little yellow car. Waterstreet said in court that Cullen’s pancreas had been removed and if he was going to drink, it would be at his own peril. “He drinks when he’s nervous, when he’s expressing himself artistically, but his pancreas can’t take it,” Waterstreet said. Cullen was on 11 medications a day and had been diagnosed as bipolar and had diabetes, Waterstreet said.

The magistrate told Cullen he was clearly an intelligent and artistic man, but he had to take his drinking in hand. “There are things that are causing you pain mentally that you haven’t dealt with and I think you need to deal with them if you have any hope for success in future, otherwise you will self-medicate and you are human and a lot of people do that,” she told him. “You will have to develop mental hardness to ensure it doesn’t happen.” The magistrate said Cullen’s drink driving warranted consideration of a jail sentence “but I don’t tink placing you in a custodial setting would be advantageous to you or the community because you won’t get the assistance you require in a custodial setting.”

Having explained her decision to Cullen that she would give him a 10-month suspended sentence if he completed a medical treatment plan, and that he was banned from driving for five years back-dated to the time of his arrest in July 2011, the magistrate wished Cullen success in his endeavours, particularly in terms of his “rehabilitation efforts”.

“Thank you so much,” Cullen said, standing before her. We all left the courtroom.

In the waiting area just outside the court, Cullen hugged his weeping father. “Okay, Pop,” Cullen said. To the media he said: “I have two cars so other people will drive me around, which will be rather leisurely.”

“It’s an excellent outcome,” Cullen said. “I’m just happy I can go back to work and not be worried. It’s [been] like a really, really bad dream.”

Elizabeth Fortescue, August 11, 2012