News

Christian Boltanski eats live native green tree ants in Sydney

Jan 13th

What does a famous French artist do at a VIP dinner in his honour, when his dessert starts crawling around in the bowl?

If you are Christian Boltanski, you are highly amused, intrigued, say “non, non”, clap your hands to your face, and finally agree to have one popped into your mouth.

I snapped Boltanski at the dinner at Carriageworks in Sydney, as Parisian art consultant Eva Albarran encouraged him to try a live Australian native green tree ant.

Boltanski was in Sydney for the opening of his massive Carriageworks installation called Chance. Dinner was cooked in situ by Sydney star chef Kylie Kwong, who has started using indigenous foods in her cooking.

And Boltanski’s reaction to the citrus-like flavour of the live ants? “Pas mauvais” (not bad), the artist conceded.

Elizabeth Fortescue, January 13, 2014, Sydney

A Chance meeting with Christian Boltanski

Jan 9th

The renowned French artist Christian Boltanski is in Sydney for the opening at Carriageworks of Chance, his grand, post-industrial installation about birth and death. I met him there, on assignment for the Daily Telegraph, and will write about our interview lower in this story.

The renowned French artist Christian Boltanski is in Sydney for the opening at Carriageworks of Chance, his grand, post-industrial installation about birth and death. I met him there, on assignment for the Daily Telegraph, and will write about our interview lower in this story.

First, some background.

Boltanski already has a link to Australia, and has been here before. That occasion was to seal an unorthodox arrangement with David Walsh, founder of Tasmania’s Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) which has earned itself a reputation for showing art with a bit of shock value.

Boltanski and Walsh share an interest in chance. Walsh is a well known professional gambler as well as an art collector, while Boltanski has for many years created artworks which imply the random bestowal of good luck or bad luck by the vagaries of life. Boltanski, a Parisian, is fond of saying that if his mother and father had made love a minute earlier or later than they actually did, he would not have been born. Someone else would have been born instead. But because his parents made love at the exact moment they did, Boltanski was indeed born. Taking this one step further during the media preview of Chance in Sydney, Boltanski offered the philosophical position that his conception prevented the birth of potential others, and that he was therefore responsible for their non-existence. A fascinating thought.

Boltanski is evidently a man of good humour as well as labyrinthine philosophical ponderings. In 2010 he made an agreement with David Walsh in which the two men are, in essence, betting on how long Boltanski will live.

Here’s how it works. Boltanski agreed to set up several video cameras inside his Paris studio. Images of whatever is going on in the studio are live-streamed straight to Walsh, 24 hours a day. This includes when there is nothing going on in the studio, because Boltanski is in bed. The videos are stored on DVD, becoming an accumulating work whose title is simply The Life of C.B.

Boltanski said he sometimes remembers to wave hello at the cameras when he is in the studio, but mostly he just forgets the cameras are there.

For the right to film Boltanski in this way, Walsh pays the artist an undisclosed monthly sum. After eight years of payments, Walsh will have paid Boltanski the agreed purchase amount for The Life of C.B. If Boltanski dies before the eight years are up, Walsh will have got the work cheaply. But if Boltanski lives to be a centenarian, Walsh will have paid dearly – and he’ll own an awful lot of DVDs of Boltanski pottering more and more creakily around his studio.

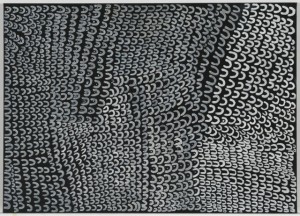

Boltanski’s work, Chance (on view at Carriageworks from January 10, 2014 until March 23, 2014 as part of the Sydney Festival), can only be described as monumental. Comprising 16 tonnes of scaffolding and 600 portraits of new-born Polish babies, it resembles a rumbling, racing newspaper pressroom. The babies’s images form one long loop of film which cascades like a human torrent around the scaffolding.

A bell clangs every few minutes, heralding the cessation of the noisy machinery and randomly bringing one of the baby portraits into focus on a video screen. Having ceased for a few seconds, the giant mechanism begins to move once more, inspiring something of the awe one feels when watching a newspaper edition coming off the presses.

A large LED screen at either end of the installation records the estimated numbers of births and deaths being experienced globally that day. (Boltanski takes these statistics from the internet).

Another element of the work involves visitors stepping up to a small console on which they will find a button. On the wall in front of them they will find a video screen divided into three horizontal strips. Each strip shows a rapid-fire succession of the upper, middle and lower parts of the face. It somewhat resembles the parlour game called “exquisite corpse”. When the visitor presses the button, the images suddenly stop and form a face. There is a one in 1500 chance of matching all three elements and forming a real face, in which case you win a photograph of the face signed by Boltanski.

The idea of Chance is that the computer chooses an individual at random. “We don’t know if it’s for the good or the bad,” Boltanski said.

Boltanski declares himself to be “not a believer”, and in Chance he dwells on the random, capricious and hazardous nature of life.

You might expect Boltanski to be a pessimist. But he’s not. He is impish, friendly, chatty, welcoming and clearly enjoys life.

I asked him what personal life event had started him thinking about chance.

“At the beginning of a life of an artist there is a trauma. In my case it was more historical trauma,” Boltanski said.

The artist was born in Paris just two weeks after the 1944 liberation of the city from Nazi Occupation. His mother was a non-Jew and his father was a Jew. During the dark months of the Occupation, it was always a risk that the Nazis would storm the family home looking for Jews. Actually, they did just that.

“The police came and they didn’t find my father,” Boltanski said.

His parents decided the best way of survival was to divorce. This would enable the mother to explain the absence of a husband who, in reality, was hiding in a very tiny space within the family home. After the war, the couple remarried. It is a remarkable story, but one that Boltanski shrugs off.

“Everybody has this story,” he said.

Boltanski said it would have been completely understandable if his parents had decided to abort him, given the catastrophic circumstances of the Occupation.

“But they decided to keep me,” he says with a smile.

Boltanski believes Chance is a positive work of art. He calls it a “factory for babies”. Yes, we will die. But we will be replaced by a never-ending stream of brand new humans, he said.

I put it to Boltanski that it’s alright for him, because his art will live on after he dies. But he still seemed unconcerned.

“What’s important for me is more to ask questions,” he said.

“It’s very important in our society that we accept we are going to die and be older.”

The analogy he used was that an old farmer who dies is replaced in his duties by his son.

“It was important the farm went on,” Boltanski said.

As for his trip to Sydney, Boltanski has enjoyed a trip to Manly where he enjoyed the beach but did not swim.

Leaving Carriageworks, I suddenly wonder: If Boltanski had gone swimming, what are the chances he could have been taken by a shark?

Elizabeth Fortescue, January 9, 2014, Sydney

On Fernand Leger and Giorgio de Chirico: interview with Jeffrey Smart

Oct 24th

As any art lover in Australia will know, the extraordinary Australian painter Jeffrey Smart passed away in his adopted home of Tuscany on June 20 this year (2013).

As any art lover in Australia will know, the extraordinary Australian painter Jeffrey Smart passed away in his adopted home of Tuscany on June 20 this year (2013).

Here is an interview I conducted with Smart on February 20, 2002, when he was 80 years old. The interview took place at the Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, where his work was to be included in an exhibition called Parallel Visions, which explored the connections between some of Australia’s most prominent artists. In the exhibition, Smart was paired with John Brack.

Artwriter: Your teaming with John Brack? Is it appropriate?

Jeffrey Smart: Well, I suppose so, yes. We’re both neat painters. We both have tidy edges. I’ll have to read Barry’s thing (the essay in the catalogue by curator Barry Pearce). When one’s a painter, you don’t think about the implications of what you’re painting, you’re just painting something you want to paint and it’s a subject you like doing. It all looks different when all the pictures are put together. Then the critics get to work.

You shared with Brack an interest in clean edges, and also in geometry?

Yes.

Did you know him?

Yes, I did know him. He came up to Sydney for a while to watch Justin O’Brien, who was at Cranbook. He was the art master, and he was completely brilliant with children. He managed to get children to paint the most wonderful things. So the headmaster of Geelong Grammar, or was it Melbourne Grammar (where Brack taught art), sent John up to study with Justin. But of course that was ridiculous because Justin didn’t know. He was just an instinctive, outward-going teacher. He had no theories about child art at all. Whereas John did. John was more an intellectual. Justin was not an intellectual at all in that way. So I think John was just confused by seeing the way Justin handled a class of children. He just was appalled, I think.

So Brack had quite set theories about child art?

Oh, yes. John was an intellectual. Very intelligent man. Not that Justin O’Brien was stupid. He was a more, um, romantic creature. Romantic as opposed to being classical.

Did you get on well with Brack?

I think so. I didn’t know him terribly well, but I always liked him and liked talking with him. But I didn’t meet him much, because he was in Melbourne and I was in Sydney.

You have had your recent retrospective exhibition at the AGNSW, another at the S.H. Ervin Gallery, you recently received an Order of Australia and an honorary doctorate from the University of Sydney, and your art is very much in demand here in Australia. Do you feel your ties with Australia are strengthening, and would you contemplate a return here?

I like to be in Italy, I like the Italian lifestyle. But my ties with Australia have always been terrifically strong, always. They’re not strengthening at all, because they’ve always been strong.

So you’ll stay in Italy?

I’ve lived abroad for too long now. I’ve lived over there for 50 years I suppose. I adore coming to Australia. I love it. I wish it wasn’t so far. If only it was where Singapore is. It’s just that extra bit that makes it so far away.

Do you speak Italian?

I speak it, yes. But mind you, I speak it like an Italian greengrocer. You know, I speaka like this. (But) people understand. I can go to dinner parties … I enjoy speaking Italian. I feel I’m slightly different in my personality and my behaviour. When I’m thinking in Italian, I behave differently. I had a great friend, Sylvia Wertheim. She was from Washington and her husband was from Philadelphia, and they lived in Greece. The first child as born in America, the second child was born in Paris, and the third girl was born in Greece. So she had three children who all spoke English, French and Greek. And she could see when they played, their deportment and their way of playing was different. And if they became too aggressive or whatever it was, she’d call out and say ‘children, start playing in Italian’. Or she’d call out and say, ‘start playing in English’. She realised that the language rules our thinking and we don’t rule the language, which I think is true.

And when you’re thinking in Italian do you become ….?

I think slightly differently.

Does it affect your painting?

No. Absolutely no connection with painting. The brain works in completely different compartments.

When you’re speaking or thinking in Italian do you become more flamboyant or …?

No, no, no, no. It’s nothing to do with flamboyance. When I’m thinking in Italian you become more logical. Well, Italian’s a more logical Latin language. It’s much more logical.

You studied with Fernand Leger. What are your memories of him?

The best story I could tell you is not so much the times in Paris, because he would only come in once a week, at the end of the week. He had his mistress who was doing most of the teaching, and then the master would come in at the end of the week and give us a criticism. But the thing that touched me most was many years later. A few years ago, I was driving through the south of France. I came near Biot, which is a town in the south of France where there’s a big Leger museum. I got to the museum and I was very anxious to see it because I like his work so much, and just as we were arriving it was lunchtime and the gallery was closing. And I said, but you can’t close. I said, are you closing for lunch? And they said, no, no, it’s a half day. We won’t open again today. And I said, oh, crikey, listen I’ve come all the way up from Tuscany to come here to see this museum and I’ve got to move on. Oh, they said, we’re very sorry. I said, but I was a student at the school. I studied with Leger. Oh, they said, did you? Oh, they said, please. Then they sent the word around, all the doors opened, people turned up and it was that sort of tradition of the French respect for the teaching and the whole thing opened up. And I’ve never seen such respect. They said, a student of the master’s here — ooh, God. And I was given the royal treatment, absolutely.

What was Leger’s mistress’s name?

I can’t remember. I think it was a name like Miranda, but I’m probably very wrong there.

Was Leger very interested in machinery?

Oh, yes. He was a beautiful designer of pictures. He’s a bit under-rated at the moment, Leger.

Did you ever run across Giorgio de Chirico?

In his old age. I never met him. But I was sitting in a very beautiful coffee shop in Rome, I think it’s called the Cafe Greco, and it’s near the Piazza di Spagna, and I went in for my morning coffee, and there seated right near me was Giorgio de Chrico with his wife. And he looked rather like a very distinguished English vicar. He didn’t look at all Greek.

You didn’t feel moved to say hello?

Oh no. He looked too important. No, I couldn’t go over there and speak to him.

Would this have been in the 1960s?

Yes. (Smart said he and de Chirico had one connection – that they showed at the same gallery in Rome.) My art dealer told me that the one obsession that de Chirico had was money, money, money, money.

Was he churning them out a bit?

Yes, he was churning them out. Copying out old works, too. His best work of course was the early work. But I’m so keen on him, I even went to Volos in Greece where he was born. He came from Volos which is a fairly big city in northern Greece, and his first training was at the art school in Athens, which is inadequate training. It would be much worse than going to art school in Adelaide.

Really?

Oh, yes (with a shudder).

What about Morandi?

I never met Morandi, but Brett Whiteley and Keith Looby did. Lucky things. I wish I’d done that. But I painted a picture the day he died, and put his name in the picture.

You can get very sick of Magritte.

As a person or a painter?

I’ve never met him. But you could get very sick of Magritte. It’s gimmicky, gimmicky, gimmick. It is a sort of gentle surrealism, but you shouldn’t see too much Magritte, really.

When I interviewed Edmund Capon last year, he said you were a bit secretive about your sketchbooks. Have you got plans to show them?

No. Well, some of them are so bad I don’t think they should be exhibited. That’s all. It’s just they’re not good enough. They were never meant to be exhibited. They were just notes.

You have said if you can draw the human body you can draw anything.

This is true.

And do you return to life drawing?

Yes, yes, yes. I still try and get models.

Do you still work every day?

Well, I’m not getting any work … (he meant, I’m not getting any work done here. He was a bit put off by his round of media interviews) … I want to get back. I’m away two weeks this time. And I’m in the middle of a nice period. I’ve got about three pictures to work on. What I’m suffering from is frustration. I can’t work.

Did you bring any artist materials with you?

No, I’m not that sort of artist, no. I’m a studio painter.

You have sometimes changed or reworked your paintings. (At his retrospective at the AGNSW, he famously took a brush and paint to a canvas that had been privately loaned to the show, to “liven up” the colour.) Have you done any of that here?

Well, all oil paintings sink a bit. It sinks into the canvas. It depends on the quality of the canvas. But you have to keep feeding oil paintings. Just like you feed horses. You’ve got to look after them. They dry out.

Have you had to do any in this exhibition?

Oh, no. Because the restorers here at the gallery know more about painting conditions than I do. They’re experts and I’m not.

Would you enter the Archibald Prize?

I can’t enter the Archibald Prize because you have to be resident in Australia.

Is that the one thing keeping you from it?

No. I wouldn’t go in for any art competition ever anyway. I don’t believe in those things. Imagine if I got third prize, it would be just so awful, wouldn’t it? It depends on the judges. And the judges could be very fallacious.

Postscript:

After our interview, Smart noticed some cracks in the dark shadows of his painting, Truck and Trailer Approaching a City. He went up close, peered at the painting, and passed a licked finger over part of the stricken area. “I will have to show the Director (his good friend, Edmund Capon),” he said. Capon was hovering about at the time. “Well, we’re not having you touching it, that’s for sure,” Edmund parried, remembering Smart’s impromptu touching up of his painting in his retrospective.

Elizabeth Fortescue, October 24, 2013

Sam Jinks exhibits at Venice Biennale satellite exhibition, Personal Structures

Jun 6th

Unsettled Dogs, by Sam Jinks

The Melbourne artist Sam Jinks has been included in Personal Structures: Time, Space, Existence, a collateral event of the 55th Venice Biennale, which opened on June 1, 2013.

I have interviewed Jinks twice before, so I thought I would dig out my 2012 interview notes with him and share them here on my website.

First of all, here is a link to Jinks’ exhibition at Sullivan and Strumpf Fine Art last year. And here is a link to my story which appeared in the Daily Telegraph. The artist’s gallery made the announcement about Venice, which you can read here.

The works included in Jinks’ 2012 exhibition included the one at left, titled Unsettled Dogs. I found this work, and others in the show, strangely moving. Unsettled Dogs is two separate sculptures, lying close together on a plinth. Although they have foxes’ heads, they have human bodies. And both heads and bodies are rendered in painstaking and perfect detail by the artist himself.

I asked Jinks if he had used real foxes’ heads or if they were models he made himself.

“That would be the sensible thing to do!,” Jinks replied, adding that he had made the foxes’ heads himself.

“I don’t know, there’s something about hand-made things,” he said.

Unsettled Dogs was partly inspired by the cynocephalus, the dog-headed human which exists in the mythology of many world cultures. The cynocephalus was described as irrational and argumentative, and Jinks has used them as a symbol for the high level of emotion involved in human inter-communication.

“People give a real illusion of being civilised,” he said. “They do a very good job most of the time, but it doesn’t take as much as you would think to get someone to tip over the edge.”

In the same exhibition was a rather fascinating sculpture called Time Machine, showing a 42-day-old human fetus in perfect, opalescent detail although massively scaled up from the real thing, of course.

Jinks is interested in how the fetuses of different types of animals are very alike until a certain point when they clearly start to become what they are eventually going to be at birth.

“I was looking at doing different animals because they all look so similar,” Jinks said.

“Then there’s points where they all start to diverge and completely separate.”

To make the embryo model, Jinks worked from electron microscope photographs in a book about embryonic anatomy.

“There’s real question marks about when you get a person ‘arriving’, because a lizard one is so similar,” he said.

“There’s this big mixing pot right at the beginning [of life], and it could go anywhere.'”

Interestingly, Jinks also spoke of his fascination with his two young children. He had noticed how each of them had “arrived” at different times. By arriving, he meant arriving as a sentient human being with whom one could interact.

So now Jinks’ work is being seen in Venice, and I’m sure that this sensitive and technically rigorous artist will attract a great deal of favourable attention.

Elizabeth Fortescue, June 6, 2013

Untitled, by Sam Jinks

Time Machine, by Sam Jinks (Sam Jinks being photographed by Daily Telegraph photographer Bob Barker, 2012

Indigenous artist’s painting on museum rooftop to be visible from the Eiffel Tower

May 26th

Dayiwul Lirlmim, by Lena Nyadbi. To be painted onto the rooftop of the musee du Quai Branly in Paris.

Sydney: One June 6 this year (2013), a black and white painting by the senior indigenous Australian artist Lena Nyadbi will be unveiled in Paris. Uniquely, the painting will be on the rooftop of award-winning architect Jean Nouvel’s museum of the world’s “first peoples”, the musee du Quai Branly, located on the banks of the Seine in central Paris.

Nyadbi’s work — enlarged 46 times from its original size — will be visible not from the museum itself, but from the iconic Eiffel Tower in whose shadow the musee du Quai Branly stands.

Lena Nyadbi is a Gija woman from Warmun, in the Kimberley region of Western Australia.

Thought to be in her 80s, Nyadbi radiated a large amount of quiet goodwill and gentle pride when she attended the official announcement of her commission in Canberra on April 29, 2013. The ceremony was at the National Gallery of Australia.

Stephane Martin, president of the musee du quai Branly, was at the announcement. So was the Australian businessman Harold Mitchell, whose Harold Mitchell Foundation paid $500,000 for the commission to be realised.

“It’s the first time a museum has commissioned a piece that will not be visible from the museum. You have to be outside the museum to appreciate it,” M. Martin told me in Canberra.

A committee of people, including former Art Gallery of NSW indigenous art curator Hetti Perkins, recommended Nyadbi’s work for the rooftop project. In particular, it was her canvas Dayiwul Lirlmim (which translates as Barramundi Dreaming) that won the commission. A section of that original painting has been chosen for reproduction directly onto the rooftop of the musee du Quai Branly.

A committee of people, including former Art Gallery of NSW indigenous art curator Hetti Perkins, recommended Nyadbi’s work for the rooftop project. In particular, it was her canvas Dayiwul Lirlmim (which translates as Barramundi Dreaming) that won the commission. A section of that original painting has been chosen for reproduction directly onto the rooftop of the musee du Quai Branly.

While the original painting was completed in ochres taken directly from the earth of Nyadbi’s homelands, the reproduction on the rooftop will be completed in rubberised paints like the paints used to mark traffic directions on the streets of Paris.

M. Martin anticipates the painting will have to be renewed every 15 years or so, owing to degradation caused by the rain, snow and sunshine of Paris.

The idea of commissioning an artwork for the rooftop came from the architect Nouvel.

“Nouvel was thinking about what he called the fifth façade for the building. That was the starting point. Why would not we discuss a commission for a new indigenous art painting?” M. Martin told me.

Workers will use one-metre square heavy paper stencils to transfer Nyadbi’s work onto the rooftop. The stencil designs have been digitised so the stencils can be re-manufactured on requirement — “as long as we don’t lose the disc, which we are very good at, usually”, M. Martin laughed.

He added that the musee will have a webcam installed on the Eiffel Tower so that people worldwide can observe the painting through different seasons.

“The Eiffel Tower is just above the museum,” he said.

I asked M. Martin why indigenous art had been so willingly embraced by Parisians.

“I don’t know why. There’s a strong connection between France and indigenous Australian art. We still acquire new artists as much as we can and the response of the audience is very good,” he said.

“I don’t know why. There’s a strong connection between France and indigenous Australian art. We still acquire new artists as much as we can and the response of the audience is very good,” he said.

The musee du Quai Branly receives 1.3 million visitors a year. But seven million people will see Nyadbi’s rooftop artwork. That’s the number of people who travel to the top of the Eiffel Tower every year.

Jonathan Kimberley, manager of the Warmun Art Centre, said the Nyadbi commission’s significance should not be understated.

“I think it’s highly significant for contemporary art, world wide,” Kimberley said “I can’t think of any similar installation into the very fabric of a city. It goes beyond just Australia. Interest in France has been steadily growing. We really congratulate the musee and the city of Paris for its vision to include such a work in such a prominent location. It’s a very powerful statement.”

Naturally, a contingent from Warmun will travel to Paris for the opening of Nyadbi’s commission, including the artist herself if her health permits it.

But there will be another celebration awaiting the group when it returns to Warmun. In 2011, a flood destroyed the Warmun comunity and the arts centre. Hundreds of paintings, according to Jonathan Kimberley, were washed away.

Luckily, however, the community’s collection of historic Warmun paintings — almost 400 of them dating back to the 1970s — were kept separately to the more recent works and survived the flood. The historic works were, however, water damaged. They have been undergoing restitution work at the Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation in Melbourne.

“They have done a brilliant job of bringing the collection back from the brink,” Kimberley said.

“It’s one of the most significant collections documenting the origins of an indigenous art movement in Australia.”

The art centre has also been renovated.

An “intercultural education program” between Warmun Art Centre and the University of Melbourne is now being established, Mr Kimberley said.

Warmun lies at the centre of Gija country, which extends for 100km in every direction from the community.

When Nyadbi paints, she uses natural ochres and charcoal found in the local landscape.

“Most people don’t get the significance. It’s literally part of the country,” Kimberley said.

When I got the chance to meet Nyadbi, I asked her whether she would take the lift to the top of the Eiffel Tower and look down on her artwork. She giggled.

“I’m not going to get up there! Too high! White people can go up there,” Nyadbi told me.

Lee-Ann Buckskin, chair of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art board of the Australia Council for the Arts, said Nyadbi had “transformed the way Aboriginal poeple see themselves contributing to the global art community”.

“Without our art we have no connection to our land. It maps important details,” Buckskin said.

She said Nyadbi’s installation would “change the Paris landscape forever”.

Here is a link to my story about Lena Nyadbi and the Musee du quai Branly in The Art Newspaper.

Elizabeth Fortescue, May 26, 2013

Addendum:

I wrote to Stephane Martin after meeting him in Canberra and posed some questions to him about the Lena Nyadbi commission.

Here are the questions, and M. Martin’s responses.

Artwriter: Has the musee du Quai Branly established any special ties or relationships with particular Australian art galleries or arts bodies while in the process of negotiating the Lena Nyadbi project? If so, which ones?

Stephane Martin: Since the beginning of this project, the musée du quai Branly collaborates closely with the Australia Council for the Arts. They helped us significantly in its concretization. This project also received the support of the Harold Mitchell Foundation. Harold Mitchell acquired Lena Nyadbi’s painting and will generously donate it to the musée du quai Branly. This project had been accompanied by the Australian Embassy in Paris and the French Embassy in Canberra.

Finally, I was also very pleased that the Australian launch was welcomed at the National Gallery [of Australia].

Artwriter: Are any future projects or exchanges planned between the musee du Quai Branly and Australian institutions? If so, can you provide any details?

Stephane Martin: Since its opening, the musée du quai Branly cooperates and forged links with Australia. Several projects have been led with Australian Institutions. For example, from October 9th 2012 to January 20th 2013, the musée du quai Branly presented an exhibition titled “The origins of Western desert aboriginal Art – Australia – Tjukurrtjanu”. This exhibition, organized in collaboration with the National Gallery of Victoria and Museum Victoria, and in partnership with Papunya Tula Artists, displayed 160 pictorial artworks and 70 objects presented for the first time in Europe.

By the moment, the following projects are in progress with Australian Institution at the musée du quai Branly:

Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islands Curators residential program:

On November 2nd 2011, the musée du quai Branly and the Australia Council for the Arts signed a memorandum of understanding to develop and coordinate a curators’ residential program for 3 years. This cooperation aims at devising and supporting projects with the goal of furthering understanding and knowledge of historical collections, and broadening international networks as well as furthering the promotion of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islands art and culture. In addition to this project provides an opportunity for curators from Australia to work with the curatorial staff at the musée du quai Branly. At this occasion, Mrs Alisa Duff, Head, Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander program at the National Museum of Australia, spent 6 weeks at the musée du quai Branly from October 15th to November 28th 2012, with the financial support of the Harold Mitchell Foundation. In return, Mrs. Magali Melandri, Head of Oceania collection at the musée du quai Branly, will be welcomed at the National Museum in Canberra this summer during 4 weeks.

Aboriginal Visual Histories (2011 – 2015):

From 2011 to 2015, the musée du quai Branly in cooperation with the Monash University in Australia, the museum of archaology and anthropology of the University of Cambridge (GB), and with the National Museum of Ethnology (Leiden NL) conduct a scientific research on the Aboriginal visual collections in Europe dating from mid 19e century to the present days. This project main goal is to a better understanding of the photographic collections of Australian Aboriginals and promotes the sharing with the descendants of Aboriginal people. The musée du quai Branly focuses it research on its collection of photographs taken by Desiré Charnay during his expedition in Australia.

Finally, the musée du quai Branly wishes to increase its Australian Aboriginal contemporary art collection. The musée du quai Branly conserves around 33 000 objects from Oceania including 1423 aboriginal art objects from Australia such as weapons, boomerangs, 250 bark paintings from Arnhem Land and 69 Australian Aboriginal contemporary paintings.

Artwriter: The banks of the Seine and the deserts of Australia are about as distant as it is possible to get. Why are the French people so interested in Australian indigenous art that they would like to install it on the rooftop of a museum in central Paris?

The musée du quai Branly is not only a museum that displays an ethnographic collection but also carries the ambition of being an original place displaying a different vision of Non-Western cultures. The musée du quai Branly proposes to show off, to the visitors, new horizons essential to oneself understanding. The musée du quai Branly does not display objects from Europe, but presents cultures from Oceania, Africa, Asia and the Americas. The Australian Aboriginal contemporary art collection holds a special place at the musée du quai Branly. It is possibly the most important collection in Europe, which has been constituted in the late 80’s, early 90’s by the curators of the Musée National des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie.

Furthermore, the musée du quai Branly presents Australian Aboriginal contemporary art in a permanent way. The Australian Indigenous Art Commission at the musée du quai Branly, which was launched in the early 2000s, is one of the most significant cultural projects for Indigenous art from Australia in France. The installation of eight artists John Mawurndjul, Paddy Nyunkuny Bedford, Judy Watson, Michael Riley Gulumbu Yunupingu, Tommy Watson, Ningura Napurrula and Lena Nyadbi are engraved in one of the musée du quai Branly’s buildings located rue de l’Université, and are very popular to the public. This project has been highly supported and accompanied by the Australian Government, the Australia Council for the Arts and the Harold Mitchell Foundation. The success of this project which is a landmark event for contemporary Indigenous art from Australia, explains my wish to renew this experience with the Lena Nyadbi’s installation on the musée du quai Branly’s rooftop.

With best regards,

Stéphane Martin