News

Jonathan Jones, Vincent Fantauzzo, Nick Stathopoulos and Justine Muller

Sep 13th

It’s been quite a big week for this visual arts writer in Sydney. Here’s how I saw it unfold:

On Tuesday morning I dropped into the NG Art Gallery in Chippendale to speak to Fiona White, whose exhibition titled Misfits I was to open the following night. http://www.ngart.com.au/artists_white.html

Fiona moved to Killcare on the Central Coast about four years ago, where she lives in a pole house on the side of the hill. Influenced by Mexican art and in particular Frida Kahlo, and also influenced by African naive art such as you see on the boards outside barber shops advertising different styles of hair cut, the paintings were pure flights of fancy.

Fiona borrows faces from “just everywhere”. She takes pictures in the street when she’s overseas, or she bases them on photographs in newspapers and magazines. People even send her photos. She looks for “a face that has character, or looks like it has a story”.

On Wednesday I interviewed artist Jonathan Jones, who was selected as the winner of Kaldor Public Art Projects’ competition, Your Very Good Idea. (My Daily Telegraph story on Jonathan Jones.) Jonathan, who used to be a curator of indigenous art at the Art Gallery of NSW, told me that his very good idea would focus on the Garden Palace which was located in the Royal Botanic Garden, Sydney, from 1879 until it burned down in 1882. The giant conflagration, a cinder from which set fire to a home in distant Potts Point, destroyed vast amounts of early historical documents and objects, including possibly thousands of indigenous artefacts gathered from around NSW and put on show in the Sydney International Exhibition which the Garden Palace had been built to display.

Jonathan told me that the loss of these objects has had a grievous impact, robbing today’s generations of indigenous people of the means to connect with many real objects from their heritage. I had no idea there were so few artefacts left.

On Thursday I went to the official announcement of Your Very Good Idea being won by Jonathan, which was held in the rose garden at the Royal Botanic Garden. The Garden Palace stretched, in fact, from the Conservatorium right across the gardens flanking Macquarie Street to the State Library — a gigantic footprint making it the most dominating building in Sydney at the time.

I ambled through the gardens to the Art Gallery of NSW to see who would win the Archibald People’s Choice.

It turned out to be Vincent Fantauzzo and his painting of his four-year-old son Luca ,which Vincent considered to be a self-portrait. Vincent’s very attractive wife, the actress Asher Keddie, accompanied him to the announcement and she stood to one side, somewhat bemused but obviously pleased, as her husband got the limelight. My story on Vincent Fantauzzo.

Going back to Wednesday, I went to St James’ railway station on the City Circle to interview Justine Muller, an artist who was brought up with an instinct for heritage, largely thanks to her mother and father who ran the East Sydney Hotel and knew Jack Mundey, the hero of the 1970s green bans. Muller is, in fact, Mundey’s Goddaughter. Muller’s large-scale drawings were of people she spotted around Millers Point, where vast numbers of people who have lived in the area have been forcibly displaced to make way for gentrification by the State Government.

The drawings were being hung inside glass cabinets along the platforms of the station, and looked fabulous. I’m sure commuters will love them. The exhibition was under the auspices of the Conductors Project run by Tristan Chant. It was the first time the Conductors Project has taken over both platforms at the station, Chant told me. My story on Justine Muller.

Thursday night saw the announcement of Nick Stathopoulos’ painting of author Robert Hoge as the winner of the People’s Choice in the Salon des Refuses. This is a wonderful picture (see left), heartfelt and sensitive, and Nick tells me a documentary is being made about its creation. This is going to be one to watch out for.

Finally, on Friday, I ducked down to Oxford St, Darlinghurst, to meet Emilya Colliver of Art Pharmacy, an on-line art sales business which has occasional pop-up exhibitions like the one I was about to see. I thought Emilya very enterprising, having tapped into the willingness of art buyers to buy on-line. Emilya said it was only works in the hundreds of</a> dollars that sold on-line, after which people tended to prefer to see the works in person before buying.

Finally, the Australian Museum has a brilliant new show on the Aztecs. My Aztecs story here.

Elizabeth Fortescue, September 15, 2014

Archibald Prize 2014: Fiona Lowry captures Penelope Seidler lost in thoughts of her home with Harry

Aug 25th

Penelope Seidler with her Fiona Lowry portrait on the day it won the 2014 Archibald Prize. Pic: Elizabeth Fortescue

It’s Friday July 18, 2014, the day the portrait of Penelope Seidler wins the Archibald Prize for Bondi artist Fiona Lowry.

Even before the noon media announcement by Art Gallery of NSW head of trustees, Guido Belgiorno-Nettis, we all know who’s won. At least, we think we do.

Penelope Seidler, widow of the towering Sydney architect, the late Harry Seidler, is in the gallery along with the media. She looks apprehensive.

Across the room, Fiona Lowry can’t help grinning. I key into my Twitter account the words, “Fiona Lowry wins the Archibald Prize with her portrait of Penelope Seidler”. My finger has only to wait for the words. A fellow journo sees what I’m doing and prods me with his elbow. We share a tiny chuckle. Lowry is an obvious winner, and her body language says it all.

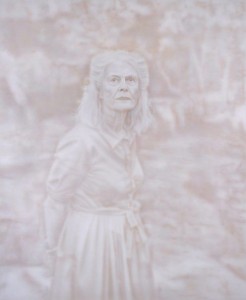

Sure enough, a couple of seconds later, Lowry wins the prize. Her portrait is a gorgeous thing. A study of a woman captured in that split second when she looks back at the Sydney home that she and Harry designed and lived in for decades. It’s where they raised their family. The store of memory must be tremendous for Seidler, and her expression in the portrait shows it. She is lost in the moment.

That frozen moment came about on one of the occasions when Fiona and Penelope visited the Killara house on Sydney’s bushy north shore. This was after Fiona had decided Penelope would make a wonderful Archibald portrait, and Penelope had agreed to sit for it.

Penelope Seidler, by Fiona Lowry. Winner of the 2014 Archibald Prize

The house was built in 1966-1967, and Penelope lived there with Harry until he died in 2006.

I spoke to Lowry on Archibald day, when the surreal nature of winning the prize was still fresh. We were about to begin our interview when Lowry’s dealer, Martin Browne, darted in to say one of the posh interior magazines wanted to do a spread on her. Browne said goodbye, and left me to speak to Lowry. It’s started already, I thought. The celebrity thing.

The first time I met Lowry, she was in the Primavera exhibition of young artists at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia in 2005. Lowry’s paintings were full of foreboding, quite disturbing. As well they might be, since they depicted people in landscapes where fearful crimes had taken place.

“Yes, I guess it’s evolved since then,” Lowry said when I reminded her of meeting her at Primavera all those years ago. “I’m less likely to go into such a horrific space, but I’ve been taking people down to Bundanon, Arthur Boyd’s property, and spent a lot of time down there making work. I love that history that’s there. So I guess with this one I wanted to take Penelope back to a place that obviously has that history. It’s an amazing space.”

I mentioned that Max Dupain had taken a picture of Penelope in the garden of the Killara house in 1967.

“I know, it’s an amazing synergy and I didn’t know that,” Lowry said. “She told me this morning. I know that photograph actually, so it’s kind of beautiful that it all came together. I do know that photograph but I didn’t know that it was taken down there.”

Lowry knew quite a lot about the Seidlers before she approached Penelope to sit for her.

“I had been a fan of Harry Seidler’s for a long time. I bought his book The Grand Tour when I was younger. I always remember (Harry’s) brother told him to buy a decent camera. He bought this Leica camera and it was all his travels around the world and he took amazing photos of buildings.”

Lowry said she made a point of visiting some of the same places while she was in Europe, using the Seidler book as a kind of travel guide.

Penelope Seider had seemed a powerful figure when Lowry first saw her at an art gallery opening. Later, as she got to know her sitter, Lowry found her “so welcoming and just adorable”.

“I really love her, actually,” she said.

Lowry was already using an airbrush back in her Primavera days, and she still does.”The airbrush never touches the canvas,” she said. “You can make it in focus or out of focus really easily.”

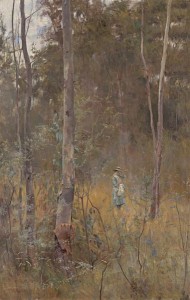

Lost, by Frederick McCubbin, from the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria

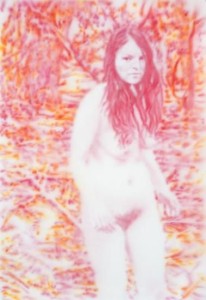

Having interviewed Lowry at the Archibald, I went home and dug out my notes from our interview when she won the 2008 Doug Moran National Portrait Prize, then being held at the State Library of NSW. Lowry’s winning painting was a nude self portrait in the Belanglo State Forest, scene of Ivan Milat’s chilling activities. It was a pretty brave painting, considering the ghastliness of the Belanglo crimes.

Lowry’s then dealer, Barry Keldoulis, told me that Lowry was “reclaiming the territory in the Belanglo forest”.

“She paints a lot of spaces where there’s been evil done. As a child she went to Bondi Public School, and came out and walked through the laneway and every street sign had a poster saying ‘have you seen this girl?’, and it was Samantha Knight, and her homely familiar streets were immediately imbued with fear and paranoia.”

In my 2008 notes, Lowry said her nakedness in the painting revealed a loss of innocence.

What I assume you shall assume, Fiona Lowry; winner of the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize 2008

“The setting is Belanglo, but it’s not specifically talking about what happened in Belanglo,” she said.

“It’s in general the malevolence of the landscape that has been explored since Frederick McCubbin painted his Lost painting. That’s a really interesting painting because there was this big fear of children wandering off into the bush in that time. So I think the landscape has always held that sort of element to it.

“I’d like in my work to play with those ideas (how evil events taint the landscape), and how you can bring these things together and make a new story out of those myths.”

Fast-forwarding to the annual Archibald Lunch at the Sofitel this month (August 2014), after the prize announcement, Lowry was on the stage with half a dozen other finalists and their subjects. Beside Lowry on stage, ready to take the audience’s questions, sat Penelope Seidler.

“We ended up in the gully at the back of the house,” Lowry said. “Penelope looked up at the house. It’s that moment that resonated with me. She’s reflecting on the space there, I guess, and that’s what that moment is.”

Penelope Seidler added to the story. “I remember it well, the moment Fiona is talking about,” she said. “I looked back and I think I said, ‘oh, I haven’t been down here for a long time’, and there’s a photo Max Dupain took in 1967 of me standing in more or less the same situation and I was thinking about that and the fact it was 46, 47 years ago and in a way nothing had changed. I was lost for a moment. It’s absolutely true.”

Penelope Seidler paid Lowry a lovely compliment. “I was lucky to be picked by her because I knew she was a good artist.”

Seidler even revealed she had bought the Lowry portrait. “I thought, ‘do I want anyone else to own it?’ So I bought it,” she said. “I don’t fancy the idea of having it hanging where I can see it all the time, but I’m sure I can find a nice home for it.”

Lowry said she had first seen Seidler at a gallery opening six years earlier.

“I was really captivated by her and felt her presence in the room, and I decided then that she was somebody I would like to make a painting about. Not even focusing on the Archibald.”

Fiona discussed her spray-gun technique, saying she began using it about 10 years ago after trying, and dismissing, spray cans. “The air brush allows fine movement and the ability to go in and out of focus,” she said.

Elizabeth Fortescue, August 25, 2014, Sydney

Erika Diettes: images of suffering go on view in Head On Photo Festival

May 16th

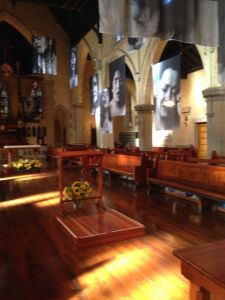

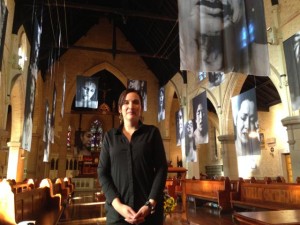

Erika Diettes’ photographic portraits of Colombian women are printed on lengths of fine silk. Numbering about 20, the portraits are delicately suspended from the ceiling of St Canice’s church in Elizabeth Bay, Sydney, as part of the Head On Photo Festival.

The peaceful interior of St Canice’s is a perfect setting for these extraordinary images of real-life suffering, of faces that call to mind the women in Renaissance paintings of the entombment of Christ.

The women in Diettes’ photographs had also endured suffering of Biblical proportions, having been forced to witness their loved ones tortured and executed during the armed terror which has beset Colombia throughout decades of armed conflict.

One of the women was made to watch as her mother’s tongue was cut out and her eyes gouged out. Another woman scooped up and drank her murdered husband’s blood in an irrational bid to absorb his life force into her own body. Another had been raped by six men but had suppressed her screams for the sake of her children who were locked in the next room.

Diettes photographed all these women as they related their stories of pain and death. During each interview, there inevitably there came a moment when words could not describe the women’s pain. That was the moment, almost transcendental in its intensity, that Diettes pressed the shutter button on her camera.

“I had the particular intention of photographing them in the moment that their eyes closed, because they are present in the exact moment of the memory of that killing,” she said.

I met Diettes at St Canice’s this week, finding her to be younger than I had expected. Her manner was warm and open. She talked about why she had titled the series of photographs Sudarios, meaning “shrouds” in Spanish.

“The basic connection for me was the holy shroud of Turin which is supposed to be the last time Jesus’s face is supposed to have left a physical impression on the fabric,” Diettes said.

“That’s my intention with printing it on silk. This would be the last impression of these women while alive.”

Even though the women lived, there was a part of them that died.

“I have been working with victims of violence for quite some time now,” Diettes said. “Many family members of the disappeared or that have had somebody killed, they always say after the encounter with violence ‘it’s like you are left dead but you are still alive’.”

Diettes sat with each of her subjects for two or three hours. A therapist was also present as the women told their stories, often for the very first time.

The series was shot in 2010 and 2011.

“All these women were from a region called Antioquia. Medellin is the capital,” Diettes said. “I took the images in rural areas of Antioquia in a place very historically hit by the guerrilla and paramilitary violence [as well as land disputes and the drug trade].”

It shows the level of trust the women had in Diettes that they agreed to be photographed with bare shoulders. One of the first portraits in the series was of a woman in a flowery shirt. Diettes thought the shirt was distracting. She asked the women to keep their jewellery and makeup on, however, as symbols of their dignity in the face of terrible adversity.

Diettes has not displayed the women’s stories alongside the photographs in the exhibition. To do so, she felt, would be to connect the stories too closely to the individual women. The sad fact is that Colombia is not the only place where such atrocities occur. They happen all over the world.

Elizabeth Fortescue, May 16, 2014

Bill Brown: Sydney artist talks to Artwriter before his retrospective exhibition at S. H. Ervin Gallery

Apr 27th

Bill Brown is a fascinating character and a great artist from the inner Sydney suburb of Newtown. Brown’s retrospective exhibition, Bill Brown: Wanderlust, is running until June 1 at the S. H. Ervin Gallery at Observatory Hill, The Rocks.

The first time I heard about Bill Brown was when I interviewed Lucy Culliton many years ago, when she was having one of her early shows at the then Ray Hughes Gallery (now the Hughes Gallery).

I asked Lucy about some of her most influential or inspiring teachers. Lucy immediately mentioned Bill Brown, who taught her at the National Art School in Sydney’s Darlinghurst.

I tucked the name away in my mind for many years, and when I heard that Bill Brown was to be the subject of a retrospective exhibition at the S. H. Ervin, I knew I just had to meet him. I lined up an interview with Brown at his Newtown studio, and wrote an article for the Daily Telegraph. I realised the extent of Brown’s influence on the Australian art world when I posted on Facebook that I was about to interview the artist. I was surprised by how many comments the post attracted. I’ve reproduced some of them below, along with Lucy Culliton’s comments when I rang to let her know I was about to interview her old teacher.

I’m pleased to be able to run the full text of my interview with Brown here on artwriter.com.au

Brown began by saying that he learned “form” as a student, which gave him the power to introduce whatever he wanted into his art works.

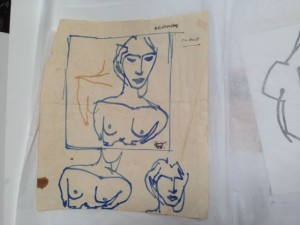

Brown: When I was 15 I left school and worked for four years in advertising. J Walter Thompson. It was a cauldron of creativity and everything was done by hand. I would see the layout people generate form and variation. (This is important to Brown. He was quite vocal about one version of a work leading to another and another. Like Matisse’s women in those drawings where he gradually refines his vision down to its essence.)

Brown said his teacher at the NAS had been Wallace Thornton.

“(Wallace Thornton taught that) every point of arrival has to be seen as a point of departure. You were never allowed to hang on. You had to keep moving. It was the 1960s and it was full of freedom and evolution and that’s how my paintings happen. In this exhibition you will see that even though I work on paintings individually, like I’ll start a painting without too tight a concept and with no clear outcome in mind, and the painting will evolve. I put something out there and it’s just to consider while the imagination takes over. The imagination is not like a solid block of something in your head that’s full of stuff. It’s a response.”

Brown said teaching was “nurturing, not lecturing”.

“I got every good at it in the end. Teaching became a great learning thing for me because I had to work out what I wanted people to understand.”

Brown said painting is not about “frozen moments”. “It’s always about creating and about moving through your ideas that you have evolved and grown as much as the painting,” he said. “So I am me, but I am always shifting.

“Once I understood that the nature of painting is an illusion, the more realistically you make a painting the bigger the lie. That’s been the basis of my understanding. I couldn’t believe in capturing something so I had to create something.

“At the same time I understood there was depth of form, colour, harmony etc and that became the language with which I make paintings. It’s like poetry in a way. These things are total fiction but the best of them is poetry.”

We looked through some of Brown’s sketch books, many of which date back years. “My drawings are like money in the bank. a bank of drawings,” he said. “I will come in (to the studio) and allow myself to be struck by something. I see something and say ok I’ll take you on. I keep on evolving and I work across a number of paintings.”

I asked him about the numerous New Guinean masks that are hung on his studio walls, and which pop up in many of his paintings. “I have included then in my life,” he said. “They are like silent witnesses that are just around me. I have always tried to just work with what’s given. Life is a given thing and if you start idealizing about it you probably miss some interesting things.”

Brown spoke about putting as much effort into the acorn as the tree. “The difference between the two is the imaginative journey,” he said.

He pointed to one of his “Ship of Fools” paintings and we talked about the hand reaching out of the water on the lower right. “To me it became the hand of God, or it could be me or somebody being lost overboard,” Brown said. “The enigma of it all. I quite like that. It’s a consequence of not having a fixed idea of outcomes.”

You might expect that Brown has been an avid traveller, given the title of his retrospective exhibition. But this is not the case.

“I travel in my mind. I’m a very poor traveller,” he said.

We spoke about how he left advertising because he was not interested in the idea of materialism and selling things. He brought his ideals into the National Art School.

“I could never aim anybody at a career because I’m a Romantic and a bit of a purist, I suppose,” he said.

“One of my little sayings is I have not confused the business of art with the art of business.”

Lucy Culliton: “He was one of my painting teachers. He was by far my best. He’s so generous. And I used to ride horses in the morning so I was always early and I would get I there before class. He was an early riser so he would come in early and I would make him a cup of tea and we would talk about my paintings. It was a lovely routine. After art school we kept good contact. I did hog bill. I didn’t share him. When you are hungry to learn, you pick someone who gets what you’re doing.”

Facebook comments:

“We all clambered over each other to get into his drawing class.” Harrie Fasher.

“I used to bring my dog Wally to art school every day and he had his name on Bill’s roll book.” Kerrie Lester.

“Bill Brown, with his warm spirit and unassuming manner, coupled with a wealth of knowledge seldom encountered, made a lasting impact on many of our lives. Many Bill-isms still direct me both in my work and in my own classroom.” Tanya Rose Fielding.

Elizabeth Fortescue, April 27, 2014, Sydney, Australia

Letter from George Gittoes: “thoughts on a haunted Afghanistan”

Mar 3rd

It’s not easy to describe George Gittoes.

Film maker. Painter. Performance artist. Keeper of illustrated diaries. So far so good.

Independent war artist and eye on the world in conflict. Yes, all that too.

Restless mind, inquiring nature, fearless pursuit of truth. Definitely all of that.

And yet you have to know Gittoes for a long time before the man’s extraordinary contribution can be understood in the fullness of its reality.

I’m planning to devote an extended post to Gittoes on this website,, quoting from the many interviews which I have had with him since our first meeting in 1995. Since that time, I have been fortunate to witness the unfolding of one of the most extraordinary and singular lives in art.

As a prelude to that effort, I’m posting an email which Gittoes sent to me and other friends from Kabul. I received it yesterday, and Gittoes has given me permission to reproduce it here. By reading the email, you will get a sense of the commitment, intelligence and empathy with which Gittoes travels to the most conflicted and violent places on earth. In the letter, Gittoes refers to Hellen Rose, the Sydney performance artist who is his partner. Here is the email.

THOUGHTS ON A HAUNTED AFGHANISTAN

Hi Friends,

Hellen and I are back in Kabul and still a few days from heading down the road to Jalalabad. There are always things to do here like securing our multi entry visas, but it is also the place to plug into the nerve centre and work out where this country is going. The streets are covered with election posters , mainly dominated by the face of Abdulla Abdulla who seems to be everyone’s favourite. Snow is on the ground from what people are describing as their toughest winter in memory, and the temperature is below freezing.

I have not been able to do much email as the internet is not working at Cedar House except, sporadically , through a cable which only Hellen’s computer will accept. Hellen is very sick with the flu.

This usually full guest house is empty . There may be four or five other guests and all are Afghan Nationals. There are no foreigners on the streets after the Taliban bombed a popular aid worker restaurant a few weeks ago, killing a large number of Internationals. No one is allowed outside. Kabul belongs to the Afghans. Most of the beggars have disappeared because their foreign targets have gone. I have not seen a single American Military vehicle or person and there are only a fraction of the security guards outside businesses as before. The skies are clear of helicopters and military flights.

I do not know how the employees at this and other hotels will survive. None of the staff have been put off , including the guards at the gates, but there is no way they can be getting paid much from the few staying here. On all previous stays here – this area is called City Centre – there has been frantic building going on all around us. Most of the buildings are designed as tourist hotels or accommodation for foreign investors and workers. They all stand partially finished but empty . The optimism has gone and work dried up.

We visited the Australian Embassy and talked to the grey suits there. Their location is a semi secret so they do not become a target. Even though we have been telling them about the Yellow House for three years they still had not gotten it into their heads to try to develop a cultural assistance policy. They just wanted us to entertain them like exotic clowns from the jungle outside. I got very severe with them and tried some shock treatment statements to draw some emotion, but to no effect.

A couple of nights ago we watched the Cate Blanchett, George Clooney, Bill Murray film THE MONUMENTS MEN about a team during WW2 who were assigned to save the great works of art of Europe. They got the same kind of bullshit opposition – “culture is not important when soldiers are sacrificing their lives” to their efforts. We felt a lot of kinship with them and many of their script lines could have come directly from our mouths.

(Gittoes then discusses another film he watched — Lone Survivor with Mark Wahlberg. The character Wahlberg plays shows that he is “totally ignorant of the generosity of Pashtun custom – and gets more and more amazed these people are prepared to lay down their lives for his”.)

Hellen and I both realise we are surrounded by similar people at the Yellow House. None of them would desert us if attacked and (they would) die with us if need be. We love the Afghan people and are devoted to them and will see this through. Hopefully the Yellow House will survive for years to come.

I never have a clear idea of what my documentaries will be until I arrive and plug into the reality of the place. Snow Monkey will be a kind of Documentary Ghost Film. So many people have died on the Afghan side, but as in LONE SURVIVOR the sympathy of the world is with the returning soldiers – psychologically and physically damaged and mourning their lost buddies. My film will give a face to the Ghost Town Afghanistan now is. The collatoral damage to the survivors of drone-Predator missiles, families and Afghan soldiers murdered by the Taliban insurgents from Pakistan, those killed and burnt by the lone soldier madmen from the US camp in Kandahar and the victims of the crossfire.

Shahida, one of the cleaning ladies at our guest house, spent the morning telling Hellen how her husband was killed by the Taliban and she now has seven children to support. This is the memory of death mourned, but I fear my cameras will be rolling on a lot of fresh blood over the next year. At the moment there is calm but everyone is anticipating the violence that is building towards the elections and all predict it will escalate, after.

The segment I find most powerful and of which I am most proud , in all my films, is the Grey Mosque in Miscreants of Taliwood. The old man cries “Blood ! Blood!” and we see the smoky spirits of the dead hovering above the shoes. This is my yardstick for Snow Monkey ….. it will be the Grey Mosque multiplied.

As we collect stories from the survivors of the violence of this war, I will begin to write up the Ghost Stories which will then be dramatised and intercut with the real . My play ‘The Afghan Book of the Dead’ was about the Hell of the American and Nato soldiers as they pass into the other side through death – this will be an Afghan Afghan Book of the Dead.

My fellow Afghan Film Makers at the Yellow House are inspired by this concept as it gives them a chance to help give faces to the lives lost that have placed this whole country into mourning. As with Love City the new movie will be a team or collective creation.

While the world is being told about the courage of the returning soldiers at medal ceremonies, our film is needed to remind people of Afghanistan’s loss and ongoing fear.

Everyone here , who I have known for some time , eventually asks if I know a way to get them a visa to Australia. They all want to escape what is coming.

Snow Monkey is going to be a lot harder to make than I thought and a lot more dangerous. It will not be a matter of waiting for threats to the Yellow House and responding to events outside its walls. I am going to have to go to the worst places, such as Kandahar and villages where drone strikes have occurred (Taliban country), to gather the stories and images. I will be well outside my relative comfort zone of Jalalabad. I do not know if I really have the courage, strength and nerve to do it, but that is the plan. For the moment Waqar and I are working on adapting to our new cameras with their complicated digital systems …..like soldiers readying their kit and cleaning their guns. We are not wanting to be fumbling around with them when things get dark.

Lots of love ,

George G

Elizabeth Fortescue, March 3, 2014, Sydney