News

Chuck Close talks to Artwriter about his hit MCA exhibition in Sydney

Feb 10th

With the Chuck Close exhibition closing at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia on March 1, I’m posting a full transcript of my interview with Close which took place on Skype. Close was in New York, and it was just before the exhibition, Chuck Close: Prints, Process and Collaboration, opened in late 2014.

With the Chuck Close exhibition closing at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia on March 1, I’m posting a full transcript of my interview with Close which took place on Skype. Close was in New York, and it was just before the exhibition, Chuck Close: Prints, Process and Collaboration, opened in late 2014.

First, a little background.

Chuck Close is one of America’s most celebrated artists. His life and work are already the stuff of legend. Close was born in Monroe, Washington, but has lived for decades in New York City. He is, at time of writing, in his mid 70s. His practice is marked by relentless innovation, constant evolution and, paradoxically, a return to the same source material which has sustained and nourished a vast body of work across five decades.

Right from his earliest days as a young artist in New York, Close was openly ambitious. He didn’t care about selling work to private buyers, he would say. He wanted to see his work in major public galleries. Before too long, he got both. Close quickly drew attention with eye-popping portraits of family and friends. These were not portraits in the traditional sense. These were a thrilling take on the centuries-old technique of the grid, used by artists to transfer an image from one surface to another. Close threw his portraits on to vast canvases, awing his audience by the size and colourful virtuosity of his work. He possessed a superhuman understanding of the eye’s ability to mix myriad individual blobs and lozenges of colour into naturalistic shades that mimicked living flesh, sparkling eyes, and unruly hair. Close became, very quickly, a darling of the art world.

By 1988, Close appeared to have it all. A wonderful wife and young family, and an address on the Upper West Side of Manhattan where many of his neighbours were famous. He commanded a coveted place in the stable of artists at New York’s prestigious and experimental Pace Gallery. His paintings were feted, and he was in demand.

But “the Event of 1988” – Close’s description – changed everything.

One day that year, after walking through Central Park to a function, Close was admitted to hospital in horrendous pain. He was suffering a spinal artery collapse, and almost immediately it robbed him of all movement below his neck. Close was now a quadriplegic, facing many months of excruciating therapies before he could return home to an entirely new life. This is where Close’s fighting spirit came to the fore. Even if he had zero movement of his limbs, he said, he would still work. Even if he had to spit paint at a canvas.

Slowly and painfully, Close regained limited use of his arms. He painted with a brush strapped to his right forearm, his left hand being used to steady the right. And so, bit by bit, Close reclaimed enough motor skills to keep working.

So, now you have a little background, here is my interview with this amazing artist:

It’s miraculous that all the plates and other paraphernalia of printmaking, on view in the Sydney exhibition, survived.

Yeah, from the very beginning I loved that stuff. I kept the plates that I’d used in college and graduate school. I didn’t know if anybody else would share my interest but I would keep them with the hope that some day they could be (in a show). I never clean up; I never throw anything away. When Terrie (curator Terrie Sultan) came to me with the idea of doing an exhibition, and I’d just had a painting retrospective, I said ‘we’re not going to be able to borrow a painting because no one will lend them again’, so we had to do something else, and I said ‘there’s this wealth of material that I’ve hung onto all these years and I have a feeling people will be interested in seeing it because embedded in the detritus of various projects is information on what I what I was trying to do’. I was firmly convinced that people really want to know how art happens. They wouldn’t have a clue; they don’t know. When it opened in Houston I didn’t have a chance to find out whether or not people spent any real time looking at that stuff. The second show was at the Met (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) so I kept running into people on the street who would tell me that ‘I’ve seen the show three times’. That just doesn’t happen. And then I would hang out at the show and watch people looking at the art. We purposefully did a minimum of signage. And I would watch people go down the line of progressive proofs and I could tell they were trying to figure out, ‘oh, this colour went on top of that colour and that made that colour’. As a matter of fact, we got 10 letters written to Nan Rosenthal the curator of the Met, saying that (with one of the works) progressive proofs 6 and 7 were reversed. Now I had lectured in front of that series of proofs five or six times and I hadn’t noticed. So if 10 people care enough to write a letter to a curator, how many more people noticed but didn’t bother to write a letter. I would think a significant number of people are actually looking at it that hard, harder than I was! And it totally mimics the process. You can see colour separations that are photomechanical and it knows all the steps you’ve got to take to get there. It will lay them out for you. I didn’t know which colours I was going to have to do. I knew the first 3 colours…. Then I looked at it and thought, ‘Oh God, it’s going to need some more orange, more green, more blue’. I didn’t know it was going to be 16, 14 colours.

Were you systematic in keeping the artefacts?

Were you systematic in keeping the artefacts?

Well, I was as systematic as a slob can be. I put them in a portfolio, labelled it, you know. I thought at the very least they had souvenir status and that they’d sort of be interesting on that level.

Are you precious with these objects now when you’re using them?

While I’m working they’re laying on the floor, they’re pinned on the wall. I don’t always keep all of the woodblocks because there’s so many of them. I just keep a representative sample of them. So we pick, like for Emma woodblock, I think we picked about eight. If we put them all up, it would have taken a huge wall.

With the time chart for the spit bite print, I wondered whether you were talking about the amount of time the plate is being immersed?

You’re absolutely right. It’s the time they’re going to be in acid. Once I had a self portrait watercolour, anyway it was the first one ….. black and white and greys, …. So I punched holes with the hole punch …. I would then put it on top of the watercolour …. If I could see the dot, it was a little lighter or darker. If it disappeared it was the same. So I digitised by hand, not photo mechanically, all those greys, and I had a list of numbers. I mixed buckets of paint that matched the grey scale. I ended up with 24. 24 buckets from white to black.

Terrie Sultan says you don’t enjoy lithography. Why?

Well, you’re just drawing on a stone with a greasy crayon. But it’s not going to print the way it looks on the stone. Let me explain: lithography is chemistry, it’s not real. It’s as elusive as chemistry. Are you a cook? I’ve noticed that cooks are either chefs or they’re bakers. Baking is like lithography; it’s chemistry. If you screw up, a little too much something or other, you can’t fix it. But if you’re making a stew (you can add this and that to adjust the flavours). That’s what you can do with stew as you slowly move towards what you want. You can’t do that with baking a cake. It has to be exactly right because it’s a chemical reaction. When you make an etching, you can get your fingernail into the groove. With a block, you can tell how rough something is. But with a lithography stone there’s a tendency for it to be slightly greasier. And I’d be proofing and I’d like the way it was. Then when they want to edition it you’d have to counter-etch it and activate the block again ….. It’s a nightmare. …. It’s not real to me. There’s no rough-cut surface I can see. I’ll tell you a wonderful story about Aldo (Crommelynck), the French printer. So we get through the whole thing and we proof it for the first time and I say ‘it’s not dark enough, I want you to change the ink, increase the pressure and we’ll heat the plate up to release the ink in the plate’. …. Americans, we’re used to doing that. He said, ‘if you wanted it to be darker you should have made it darker. I only use one ink, one amount of pressure, and I never heat a plate’. …. I said ‘that’s all well and good but the thing is not dark enough’. So when he wasn’t there we changed it, but it’s typical of a particular kind of professional printmaker. They can really drive you nuts. I wanted to make a better proof and I’m willing to do anything to get that to happen. I didn’t want to waste that plate; I just wanted to get more out of it. When I was Gabor Peterli’s assistant at Yale, I only made monograms. I was only interested in the first one. I would do anything to get that print to look right. But then I went to work for (I couldn’t catch what he said here), and I was supposed to make 50 prints that looked exactly alike and I had no patience and I was a slob, so I got fired the first day. And he said, that’s alright kid, you make your own prints one at a time, but it’s not going to work for me. The traditional printer wouldn’t have any idea working on one of my monoprints how I had done it.

Because you massaged it to be the way you wanted?

Because you massaged it to be the way you wanted?

Like paint; like paint does. Bob is in the show, and also Keith. The MoMA gave me a show about the making of that one print (Keith.) It’s the first print I made as a mature artist. Then it went on the wall and everybody liked looking at it. So I said, ‘people really want to look at this stuff’. Now (museums) find themselves doing it because they’ve found Matisses and Picassos and other people’s progressive proofs. They’ll sometimes put them up and show them. At the time, they weren’t interested. The plate (for Keith) had oxidised and every fingerprint and everything. Like a dark chocolate patina. So I told the art handlers ‘help me take it off the wall, I’m going to go clean it’. They said ‘you can’t touch that’. I said ‘why not? It’s mine’. They said, ‘well the union requires that anything moved in the museum is moved by an employee of the museum’. So I watched when they went to lunch, and the next day a friend of mine took the plate down off the wall, we went to another floor into the men’s room, took it into one of the stalls, and I cleaned the plate with Brasso, cleaned the whole plate, then I sprayed it with fixative and we took it back and put it on the wall. They said, ‘what happened to this?’ (I said), ‘I don’t know’. (He hasn’t seen the plate since MoMA.) I’m so disappointed (that I couldn’t travel to Sydney) for many reasons, chief among them was seeing the plate and the proofs again. I always think of a retrospective as being a – what happens when a family gets together for a special occasion? A reunion? I think of it as a reunion and all of my children come together who I’ve made individually and I see them together. So I haven’t had a reunion with them.

(Close said he had never visited Australia).

I couldn’t risk my health. You know why I was taking a nap? In the morning I get up, have breakfast, work for a little bit, lie down 11 till 1, or get pressure sores, bed from 3 to 5, dinner between 5 and 7, back to bed from 7 to 11, get up, go back to bed and sleep all night. So all those hours I have to not be on my rear end, which is a colossal waste of time.

Elizabeth Fortescue, February 10, 2015

(My thanks to the MCA for the images used in this post.)

Lucy Culliton survey exhibition at Mosman Art Gallery

Dec 15th

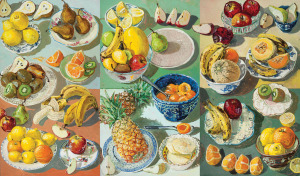

Summer Fruits, 2000, by Lucy Culliton

As the tens of thousands of people who enjoyed it already know, the recent Lucy Culliton survey show at Mosman Art Gallery was quite wonderful, and a great tribute to an artist whose contribution is already substantial but who will go on to do so much more.

In September (2014), I was lucky enough to sit with Lucy’s dad Tony Culliton at a wonderful lunch to celebrate the exhibition, titled The Eye Of The Beholder: The Art Of Lucy Culliton. After lunch, Lucy took to the stage with compere Simon Marnie and artists Euan Macleod and Peter O’Doherty in a conversation that shed light on Lucy and her work.

Here are some observations from the notes I made that day:

Lucy’s menagerie: People are always interested in Lucy’s love of animals, and the number of creatures she has gathered around her. Lucy said she currently has 42 sheep, two pet cows, a pet pig, four dogs, a fowl and a magpie. She recently looked after a wombat while taking it to an animal rescue person.

Lucy’s new studio: “I have just purpose-built a big studio [on her farm, Bibbenluke Lodge, at Bibbenluke, NSW]. I was struggling in an existing shed.

How can you resist this gorgeous horse painting by Lucy Culliton?

But it wasn’t big enough so I have just built a really big, fantastic studio.”

School: “I was hopeless at school. I dropped out at the end of Year 10. I took a while to mature.” Lucy worked in graphic design until the age of 27 when she enrolled in the National Art School in Sydney. One day, the veteran art dealer Rex Irwin addressed the students at NAS, telling them that for every 100 of them, only one would achieve. “I felt I was chosen!”, Lucy said. At this point, Euan Macleod chimed in: “We were told it was one every two years.”

Dyslexia: “I’m quite dyslexic. Working as a designer did not suit me. I didn’t know what to do. I just wanted to be a painter but I wasn’t strong enough to start. I needed an in. I needed a peer group. I kept horses at the Showground also, so I wasn’t a drinker.” Lucy made a bit of money while she was at art school by riding other people’s horses at the old Showgrounds, now Centennial Parklands Equestrian Centre. “I love horses,” she said.

When did you realise you were an artist? The artists had a question about when they realised they were an artist. This brought out a lovely bit of light banter.

“I’m hoping next year,” said Euan, who is a very prominent Australian artist.

“I think it was about 4.30 on a Tuesday, ” said Peter, ever the clown.

Lucy’s answer was illuminating.

“I haven’t painted now for two months and I feel like I am not a painter.” Various life issues had kept her from the studio. Lucy has also told me in the past that, once she has finished painting for an exhibition, she normally goes into a semi-dormant stage as far as her work is concerned.

Euan added: “What Lucy says is true. You get pulled away from your work. Sometimes you feel you aren’t getting enough time to think about what you’re doing and you get back to the studio being a sanctuary and the studio being a special place.”

Simon Marnie, Lucy Culliton, Peter O’Doherty and Euan Macleod

Routine: “I love routine,” Lucy said. After feeding all her animals, she’s in the studio by 9am. “After lunch, I decide whether to go back to the studio or do some gardening or mow the lawn or something like that.”

Peter said he and his artist wife Susan O’Doherty tend to work until dark in their shared studio at their home in Coogee. They then put out the work on the coffee table, watch TV and have dinner and keep going.

Relaxation: It sounded like all three artists are incredibly hard workers. Euan said he’s not very good at relaxation, and Lucy said all her trips are painting trips. “I don’t go on holidays,” she said.

On finding her property in rural Bibbenluke, which is a former trout fishing lodge: “I just found ‘Lucy-land’,” Lucy said. “I found the place that suited me. It just happens to be six hours south of Sydney. All the outdoors things suit me. The house is a bit run-down, so it’s comfortable for my animals. I also found Sydney is far too social. It takes a lot to get me away [from Bibbenluke].”

Art prizes: There was a funny moment when we learned Lucy’s work, which is hugely popular and widely collected, was recently rejected from the Bega Art Show!

Euan said he missed Lucy at NAS, where he taught, by a couple of years. “Everyone was talking about this student who was there a couple of years before.”

Finding home: Lucy said she would still be at Bibbenluke Lodge “until I’m 80”.

A Lucy painting from her Mosman Art Gallery retrospective exhibition

“I’ve just arrived at where I’m comfortable,” she said. “It’s a place that feeds me full of ideas and (where) I can make my work. And it’s a beautiful garden. It’s the best place in the world.”

On advice for emerging artists: “Don’t take any advice. Just do what you want to do,” Lucy said.

Elizabeth Fortescue, December 15, 2015

Elisabeth Cummings: on view at Shoalhaven City Arts Centre in Nowra until February 21, 2015

Dec 14th

Tom Carment on drawing, bushwalking and the Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial

Dec 9th

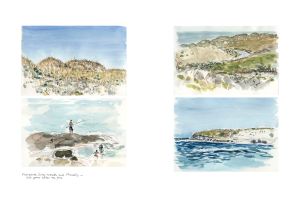

Tom Carment with one of his portable painting boxes

Tom Carment is one of the 10 artists selected by curator Anne Ryan for the Dobell Australian Drawing Biennial exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW. I popped in on Carment at his home on a quaint and atmospheric laneway in inner Sydney. We were going to talk about drawing and bushwalking. Carment’s new book, Seven Walks, Cape Leeuwin to Bundeena, has just been released with gorgeous photographs by Michael Wee to accompany Carment’s drawings and text. That, along with his current exhibition at King Street Gallery on William, has been keeping Carment somewhat busy this year.

Artwriter: You’ve got numerous things happening: the book, the Dobell drawing exhibition, and your own exhibition at King St.

Carment: They’ve got 128 of my little watercolours (at the AGNSW show). I’ve done quite a lot of jacaranda paintings recently. And Neilson Park and Coledale (and other locations in city and country).

Is all this a coincidence, or was it planned to happen together?

Tom Carment

It’s been kind of hectic. Nearly four years ago Jan (Carment’s wife Jan Idle) said “let’s do the Cradle Mountain Overland track as a family”. I think Matilda was 11 and Fenn was 16 and Felix was 18, something like that. And she really planned it well because we did it with carrying our own food in, and tents. We did the six day walk and this kitchen table was covered with ziplock bags and we marked them off every day and we planned all the food. Michael Wee is a friend through Crown St Public, our kids went to school together. Andrea his wife designed the book. We have an ex Crown St Public School parent coffee still, even years after our kids have gone on to high school and beyond. We still meet up at the Belgenny Café at Taylor Square. I was telling Michael silly anecdotes about our adventures on the walk – getting completely wet, me getting a leech inside my mouth, things like that, and he loves walking and photographing landscape. A few weeks later he came back and said, “I’ve got a really good idea, why don’t we do this book together, walks in Australia?”. He thought it was a good hook to hang a beautiful book about Australian landscape. We weren’t really experienced bushwalkers. I’ve always gone out to paint in the bush, but not camping out overnight with my own tent and my own food; usually I go to the Royal National Park, and I’ve gone camping with the family where you pull your gear out of the back of the car and walk 25 metres and put up your tent at Honeymoon Bay or somewhere. So it was a learning experience for me. Michael and I did all the same walks, but we didn’t do them all together. (Carment undertook some of the walks with other friends.) I tried to incorporate some of the conversations we had on the walk. Because when you go on a walk you have conversations you wouldn’t have in the rushed schedule of everyday life. Especially with our own kids, they started quizzing us. They asked Jan and I about our lives. “What were doing when you were 16?”, that sort of thing. That was really nice. You don’t talk all the time when you’re walking; you might walk for an hour with someone and not say anything. When you come back from a longish walk I think the anxieties you had are put in perspective and liitle things you thought were terribly important aren’t so important any more. I think it’s very kind of refreshing.

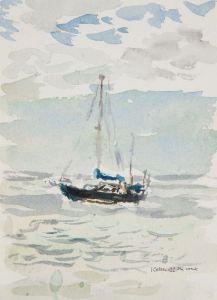

A work by Tom Carment

You’ve always gone into the bush to paint. Did you enjoy the long walks and camping?

Yeah I really enjoyed it, except sometimes it was a challenge to get in my painting with the walking. Michael will walk along and see something and stop and take a photo of it. The sort of paintings I have in this book, of drawings or paintings, they start with a line drawing and I add the watercolour, so you could call them drawings. It takes me about 20 minutes, half a hour, to do one. If I was walking with other people, I might sneak one in during morning tea break, at lunchtime perhaps I could do a watercolour, and once I’d set up my tent in the late afternoon, before it got dark I’d rush out and do some painting and when I first woke up in the morning I’d rush out and try and do a painting then. So I had to really make the most of my time.

Some of the walks were already familiar so I had a greater wealth of watercolours to draw from, for example the Otford – Bundeena walk. I first did that walk about 35 years ago. And the Cape to Cape walk, because my partner Jan is from WA, we’d holidayed on that coast before. We used to go across to WA to see Jan’s parents and we’d go down to the mouth of the Margaret River which is half way up the Cape to Cape walk; it’s day three of the Cape to Cape. And when we’d we stayed there we’d gone and done bits of the Cape walk.

One of the challenges is you can’t take too much?

I also had all the breakfasts for the family, so my weight diminished over six days. I learned to take just an A5 and an A6 size pad and a little Tupperware container with my watercolours and a couple of little enamel plates which I put face to face. I use tubes and then I use these pens which are permanent sort of things. They dry quite quickly and when I put the watercolour wash on they don’t blur out.

You’re in the first Dobell drawing biennial at the Art Gallery of NSW. (The biennial this year replaced the former and well-loved Dobell Drawing Prize, in which Carment was hung three times and was rejected 17 times.)

I guess I’m lucky, it was my time. I let (Anne Ryan) pick the eyes out of what I’d done in the last two years.

Where does drawing fit in to your practice?

It’s like the core of what I do, really. It’s the beginning. And sometimes it’s all that’s needed. I’m trying to convey the sensation of, you know, when something jumps out at you as you walk along, something that’s not just beautiful but interesting. And rather than think, “I’ll take a photo and go back to the studio”, I’ve tried to make it so I’ve always got something with me in my backpack so I can make a picture really quickly while I still have that sensation in my head.

We had an exchange student with us recently, a German girl, and she did hockey and I’d take her out to Daceyville twice a week and so I did a whole series of pictures around Daceyville. I thought, “I’ll use my time rather than sit and watch them play hockey”. My life has centred a lot around my family and working from home. You come home and cook dinner. Jan and I have always shared the children and the domestic stuff. So I’m lucky like that.

A work by Tom Carment

Are you planning to do any more long bushwalks?

I’d like to do some in NT and Qld. Carnarvon Gorge. Larapinta. Hinchenbrook Island. Katherine to Edith Falls.

Elizabeth Fortescue, December 9, 2014, Sydney

Surrender to Joshua Yeldham’s exhibition at Manly Art Gallery and Museum

Sep 29th

Joshua Yeldham’s mid-career survey exhibition, Surrender, which was opened by actor Richard Roxburgh at the Manly Art Gallery and Museum on September 19, 2014, gave me the opportunity to meet and interview this extraordinary artist.

Yeldham creates much of his work on board his romantic old motor cruiser while it is moored on the lower reaches of the Hawkesbury River around Refuge Bay.

I asked Yeldham about his new book, also called Surrender, which was launched in tandem with his exhibition. The book is a peon to his 10-year-old daughter, Indigo, who was born after Joshua and his wife Jo went through the IVF program. Yeldham said he made a conscious decision to move to a watery environment while trying to conceive a child.

“That barren period was while I was in the desert, so it connected to the desert being the dried mother of all oceans,” he said.

When Yeldham began to dream of an owl which swooped down and stole his and Jo’s “potential children”, he drew on what he learned in his travels throughout North Africa and began making charms to appease the owl.

“Finally Joey became pregnant, and I started to celebrate the owl and give thanks to the owl and to make musical paintings that are owls that play music, which is melody, rhythm, repetition, learning to push through adversity and maintain navigation,” Yeldham said. “So the owls over 10 years have transcended from being ominous to being navigators for me. And also maternal.”

The owl is not a common Hawkesbury River inhabitant.

“They’re very secretive. All nature in the Kuringai is very secretive. It’s not an abundance of blatant wildlife. It’s like an ancient temple for me, the bush. It’s so removed from humanity and all that’s left is the traces of enormous forces that push boulders down gullies and forces of erosion and weathering of sandstone and tidal currents that don’t permit humans to last long there.”

Yeldham explained his philosophy, underlying all his art, that new life springs from destruction. He believes this is as true for human life as it is for, say, regeneration by fire in the Australian bush.

Yeldham spoke about growing up in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, and joyous holidays at his parents’ hobby farm on the Hawkesbury River at Ebenezer.

“When I was around 10, my mum and dad divorced and the farm became barren. The family unit stopped to exist. We still own the farm, but all of us let go of it because it contains such powerful memories and joyful memories and then in the separation it lost its fertility again, the ability that we would all grow as a family. And I wanted to reclaim the river as a new husband and as a father to my children and to teach my children the knowledge of the river, and it was a calling, really, to return.”

Yeldham sometimes takes his boat up to the old farm. But he gravitates to the “mangrove country” near Spencer and in the Kuringai country in locales such as Smiths Creek and Yeomans Bay. Yeldham said he loves the mangrove country because of its physical hostility as far as humans are concerned. “When I spent time in there, there’s no reference to human life. You can camp there and you’re lost in time.”

I asked if Yeldham goes to the river to paint alone. He said, emphatically, yes. “I go to the river to collapse and then create, which is creation coming out of the burn-off. That’s one of the most ancient stories any of us can access. And to not fight that process but to embrace it with great elemental awareness and gratitude.”

I asked Yeldham if he planned a sequel to his book, Surrender, that would mainly be for Jude, his six-year-old son, also born by IVF.

“That’s what everyone’s asking. We’re busting to do that. We’ve all been in Africa, all of us, since then, and it’s so much about my son the way he saw Africa and travelled. So yeah, why not?”

Elizabeth Fortescue, September 29, 2014