News

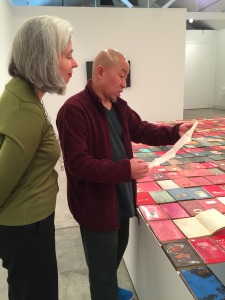

Guo Jian and Ah Xian

Aug 1st

An extraordinary thing happened at the Casula Powerhouse last Friday night.

It was the opening night of the new Refugees exhibition, which includes the now Sydney-based Chinese artists Ah Xian and Guo Jian.

Cast your mind back to 1989 and the infamous Tiananmen Square massacre of pro-democracy protesters by government armed forces.

Ah Xian and Guo Jian were both there, both witnesses to the slaughter.

Guo Jian was a student protester and hunger striker inside the square. Ah Xian, a commercial artist at the time, had cycled to the perimeter of the square every day to see what was going on.

Ah Xian had told me a few weeks ago about his memories of Tiananmen Square. He had seen many bodies stacked on top of one another in a bicycle shed at Fuxing Hospital. He presumed that the hospital was overflowing with the dead and dying, and that the shed was a makeshift morgue. I asked Ah Xian who would have put the bodies in the shed, but he wasn’t sure.

Fast forward to last Friday night at Casula. I’m chatting with Guo Jian, telling him about my interview with Ah Xian. When I tell him about the bicycle shed with bodies in it, Guo Jian says: “Yes, I was one of the people putting them there”.

Guo Jian recalled slipping on blood an inch deep on the ground, and seeing people die before his eyes.

So here were these two men, 27 years after they had both been at Tiananmen Square. Somehow, to me, it seemed quite remarkable.

Ah Xian did his first piece of performance art on opening night of Refugees. For three hours he sat completely still in a purpose-made box. Only his head and chest were visible through a perspex display case at the top of the box.

Those who know Ah Xian’s porcelain painted busts will immediately recognise the similarity between them and the performance.

Guo Jian’s work in the Casula Powerhouse exhibition included a picture that he made especially for the show.

Titled Picturesque Scenery No. 27, the work is a pigment print on photo paper in 26 panels. It exactly mimics a famous, Song-dynasty painting of fish swimming in a pond.

However, get up close to Guo Jian’s version, and you can see the picture is made up of literally millions of tiny photographs of people’s faces.

These came from Guo Jian’s home town, which is noted for its beauty.

But Guo Jian was appalled to return there after many years to find enormous amounts of rubbish in the river whose pure water he often drank as a child. He photographed the celebrity faces on wrappers discarded in the river, and now uses them as elements in giant collages. It is only up close that the viewer can see these tiny faces, not much larger than a match head.

Elizabeth Fortescue, August 1, 2016

Mike Parr turns blowtorch on global warming

Jun 27th

Anyone at Sydney’s Carriageworks at 6pm on Thursday March 17, 2016, would have witnessed an extraordinary event at the centre of which was the well-known experimental artist Mike Parr.

In the performance, Parr and several assistants doused petrol on $500,000 worth of Parr’s beautiful etchings. Parr, without flinching, then tossed a flame on to the etchings which were all destroyed in a short-lived but spectacular ball of flame that left the audience gasping.

I joined a crowd that assembled just before 6pm. We were handed a sheet of paper which quoted various scientists on the topic of global warming. At this stage, the 120 etchings were carefully laid out in a grid, each one weighted down with its corresponding etching plate. We had no idea what Parr had in mind.

The crowd grew, as we had been told the performance would be at 6pm sharp and would be over in minutes.

Right on 6pm, Parr and about four helpers walked quietly and resolutely out of Carriageworks and began ceremonially pouring the petrol all over the artworks. The fire burned for several minutes, creating a cloud of dark smoke, then quickly died down. Soon it was reduced to a few random embers. Bits of paper were picked up in the brisk wind and blown into the gutter. Mike remained impassive, watching, as all this happened.

After perhaps five or 10 minutes, Mike simply turned, said “thank you”, and walked back into Carriageworks. I learned later he then went home, rather than staying around for the Biennale drinks party. (The performance was part of the Biennale of Sydney, 2016).

Next day, deeply moved by Parr’s performance and intrigued to talk to him about it, I recorded this conversation with the artist.

I told Mike I went to the performance the night before and that my reading of it was about global warming. That the future is so grim, why worry about the past?

Yes, it is sort of that. But I’ll just expand a little bit on that. My thinking was, in putting it together, initially I thought I’d write a spiel that kind of extended what you just said synoptically. But I thought, no, I’ll just go straight through to the authoritative voices that I respect and I’ll just quote to make a clear picture of where we are scientifically with climate change in the post-Paris Agreement situation. So that little hand bill I handed out would help.

So my thinking was that this really is drastic. I’ve been following the science of climate change ever more intently for probably 20 years I think. I read (James) Lovelock’s books in the 90s and that sort of alerted me to the issue and then I got into the hard science and I’ve tried to keep up with that as the picture’s emerged.

IMG_9648 (Click here for short video of the performance.)

Parr said scientists he has talked to believe we are in the middle of the sixth great extinction.

So that means that anything much bigger than a cockroach, certainly large mammals, we have no capability of being able to evolve a tolerance to climate change in the time frame that is now imposed on us. So the sixth extinction is going to be catastrophic. By the end of this century not only will we be in terrible stress but we’ll be unaccompanied by all that animal life. What’s really interesting is in Paris, the 1.5 degrees of warming, I mean that is just total nonsense. We would have had to have stopped our emissions yesterday. Flannery makes that very clear. India has now declared it will mine and consume a billion tonnes of coal per year. Australia exports half that amount, Indonesia is now the largest coal exporter in the world. My reading of all this is we’re heading into a situation. You begin to think that this might be the limit of our human capacity. The general human population in democracies, the ever increasing population of the world. It may be just the simple fact of human psychology, we can’t accept this kind of situation. We can’t assimilate it. The reality of it can’t be absorbed. It can by scientists because they’re constantly working with the data, they’re doing the research and they have to face the implications of their own findings. But for the general public this is something that doesn’t seem able to be absorbed. And so it’s a sort of tragedy. My feeling is we can’t make the sacrifices. None of us can make the sacrifices that are really required. Lovelock talks about putting the democracies onto a kind of wartime footing, the kind of controls and rationing we saw to fight the Second World War. But in a democracy now no politician is going to go there, there’s never going to be a mandate to do that sort of thing. So we’re trapped by a sort of inertia. I feel as dramatic and melancholy about it as that. I think our children and grandchildren are all going to turn to us in the coming 50 years and say ‘why couldn’t you act grandpa? Why couldn’t you make the sacrifices, why are we in this situation?’ And then it’s my feeling that as it becomes evident that we don’t have a future, I think the past becomes unbearable. Dante becomes unbearable, Rembrandt becomes unbearable, Shakespeare becomes unbearable. Because really great art is actually proposing a kind of way into the future. If there’s no future, that essential humanism of really significant culture becomes somehow or other unbearable. Because it’s creating a path into a future that’s no longer worth inhabiting. So I began to feel, I’m just a minor figure in the scheme of things, but I’m dedicated to what I do and I just feel that at this point in time, my ambition was to push the idea of subjectivity to an extreme, to investigate it as a kind of limit space. That’s where all that performance work’s coming from, that’s where the self portrait project comes from. I treat the self portrait in the most, well you know the fashionable word is deconstructive. But I treat it in the most critical and sceptical way I suppose. I treat that whole idea of subjectivity, self, ego I subject it to ….. I’ve got this interest in psychoanalysis and have so for 50 years I suppose ever since my university days I became enthralled and there may be obvious reasons why I would have done that. But anyway I’ve subjected the whole idea of subjectivity to a sort of scathing, analytical scepticism but collided it with our political world, because that’s the only way in which you can really engage with human problems in any depth is if you do it from the standpoint of your own extremities as a social being. So what I feel now is it’s got to the point where my feeling now is I’m using my art as a kind of medium and I’m using it to make a final statement. I’ve accumulated all this work, I’ve been very prolific over the period of the last 45 years, I’ve produced an enormous amount of work really, and I think it’s available now to be used to make this kind of statement. It was clearly in my mind it was a sacrifice worth making.

Parr said making prints is now unbearable for him. He said categorically that he will no longer make any more prints.

it’s sort of become unbearable for me. Churning out these sort of bank notes, you know? We need to make a living but I’ve now reached the point where the only way I can establish any sort of meaning is to use this stuff as a sort of medium. That was the idea behind the performance. I just felt as though this was the moment where I sacrificed a sort of specious concept of value. The values associated with our consumption-driven culture. I sacrificed a commodity for the sake of an idea, and that’s the point of the performance.

The prints you burned last night were recent ones?

No, they span the 28 years of my work. Some of them are unique state, some come out of editions but they’re very small editions. (Parr decided two or three years ago to tell his printmaker to close the editions off, he didn’t want to produce editioned prints any more.)

There’s probably well over half a million dollars’ worth of prints there (that were destroyed by fire in the performance). They span the period from 1987 through to the present. But I’ve stopped making prints now. I declared that last year when I kind of had this kind of crisis and painted out a whole exhibition of prints at Anna Schwartz’s (gallery). These were all prints I’d worked on for two years, they were all unique state, huge things. I said it’s like the arrival of the Spanish Armada. You put them up and there was all this interest and everyone seemed to think they were a sort of final state of the level of printmaking and I started to become very uneasy and at the end of the show I decided to paint them all out as a performance. So I think that set me on the trajectory. So it’s sort of very interesting because the crisis has emerged in the context of the whole notion of expression, what does that mean, and then in the context of this much bigger problem, that kind of submerges all of us and certainly individually it becomes our measure as it were, and I put that work forward on that basis.

The ones you burned yesterday belonged to you?

Yes, they belonged to me.

Parr spoke about how his relationship with his master printmaker, John Loane, was initially strained by Parr’s idea to set fire to the works.

He has now understood why I’ve done this. And because (of that), I then said, ‘John I’m going to go further. I’ve got to take all this work, I’ve got to use it to make new art that’s very political, that’s about these issues that obsess me – this is this problem of climate change and what it’s going to do to humanity’. I said ‘we’re going to have to use the prints as a medium now, now just preserve them as a work, but use them as a medium to make new critical art’. And he understands that, to his credit, he understands that.

Was he there last night?

He was at last night’s performance. He came a little late, and still very anxious, but he said to me at the end of the evening that it was marvellous, he understood and he was there to pick up the charred copper plates and scraps of burned prints. He felt that they should be picked up and he should take them back to the print workshop and that we should look at the bits and pieces together and we should put them in a box of some sort. Well I don’t know about that, but it was just very moving that he was prepared to be there and collect the remnants.

I noticed audience members doing that.

Well they can do that and it doesn’t worry me in the least. I think it’s lovely that people want to do that.

When I put a video of the fire on Facebook, lots of people commented that’s it was strange to protest against global warming while at the same time putting more toxins into the air.

Well I’m certainly putting toxins into the air, but actually that’s what they need to see. So if they see that and say ‘that’s terrible, that’s exactly the problem of global warming’, well it is. But it’s on a very small scale, it’s almost homeopathic. That’s exactly the problem. No disrespect to anyone because I understand exactly the impulse. It’s like our impulse to manage the garbage. It’s got to a point where governments can have cleanup programs, they’ll announce we’ll have a little army of people out there picking up bottles and papers as though that was a sufficient response to global warming. It’s actually a displacement activity. It’s very moving, it’s very important that people are concerned. But it’s concern that doesn’t address the problem. It’s like someone’s got cancer and you put all the emphasis on giving them orange juice to drink. Vitamin C can have some efficacy but in a cancer emergency it’s not much of a response. And it may well be just an avoidance ritual. You’ve got very easy emotional responses, so you know you say, ‘Oh look there’s a cloud of black smoke over Mike Parr’s action. That’s adding to climate change’. My goodness gracious me. And India’s proposing to burn a billion tonnes of coal a year to fire its coal power stations. And China burns the equivalent of all of Australia’s annual exports of coal in one month. So that’s the real statistic. And if I need to make the point by sending up a little black cloud ….. Not to see that, is not to see the real problem. So that’s the answer to that one. And I’m not being arrogant about it. It’s very important to call people out on this one because feeling self righteous about dividing up your rubbish. It’s very important to feel you’ve done it properly and that the glass goes in the glass container and the paper goes into the paper container. It’s all important, it’s in large part a commercial imperative at this stage because that’s the way it’s recycled and recycling is very important, but it’s not going to deal with the problems that really face us. And we’ve got to be aware of that. So my action is essentially a symbolic one. But it’s using all of the real combustible issues of the problem.

Is this an on-going thing? Will you destroy more of your work this way. Or was that a one-off?

I don’t know. One of the risks is that in the art world if you do something that has a major impact the risk is then that people expect you to repeat it and before you know it it becomes a kind of style. It’s a bit like Andy Warhol painting soup cans. The next thing you’ve got a very marketable sort of line in burning your own work. And I don’t intend to do that. So as far as I’m concerned it’s a complete one-off, because to repeat it is to enter a zone of ambiguous banality, really.

In burning the prints, did that destroy the plates as well?

The plates will be destroyed because all that copper, that’s going to be the next conversation with John that I’m going to just sell all of the copper plates on to a scrap merchant shortly. I don’t want any more prints pulled. I don’t want to produce any more prints at this point.

Never in your life?

No. No more prints.

So that print project is over?

It’s over. And it was given a sort of fatal blow I suppose with the painting-out performance last year because that opened up this void. And following this burning I’ve made the decision that I’m not going to make any more prints. So I’m going to destroy all the plates.

As long as I’ve known you, prints are a large part of what you do.

It’s a massive transition but I think that I’ve also realised that I also need new challenges. I’m old now, I’m sort of 70, and I’ve suddenly realised there’s just a few years to go and I want to speed things up. I want to be more engaged rather than less engaged. I don’t want to be slowed down by people’s expectations. I want to exceed their expectations. I want to make new work. Challenge myself. I want to feel vulnerable at a very fundamental level. Because at that level you most engage people.

I told Mike I would put our conversation on my website.

Terrific. I think we ought to get it out there. You do really understand the tensions in this piece. The important aspect of the performance is that it raises lots of questions that don’t get resolved at the level of the normally fairly glib resolutions that the art world goes for. It doesn’t just invite a resolution at the level of art. It’s dominated by questions of content and meaning that everyone has to contribute to.

Coming back to the issue of value, it’s really important, because you could say we fuelled the performance in a number of ways. We fuelled the performance by dousing the prints with petrol and dropping a match. Petrol is obviously one of the fuel parameters for the work, but the other fuel was the monetary value. The question of value there was turned into a kind of fuel. Ideas were fuelled by the value of the prints, by the act of sacrificing the prints, of burning the prints, and the visibility of fossil fuels. The black cloud that everyone abhorred is the thing that’s coming out of the back of their motor cars in a disguised form. You no longer see puffs of black smoke but you’re still getting carbon dioxide and all of the other greenhouse gases.

ELIZABETH FORTESCUE, June 27, 2016

Snow Monkey: a review of George Gittoes’ new film at its Sydney premiere

Nov 11th

Shazia, from George Gittoes’ documentary film, Snow Monkey. Picture supplied by George Gittoes.

I’ve just been getting to know some of the street kids in the roughest parts of Jalalabad. This is Afghanistan’s second largest city, and reportedly the most dangerous city on earth.

I met wide-eyed, gorgeous little Gul Mina, aged about five, who collects discarded cans in hessian bags and sells them for a few rupees to support her large family.

I met Irfan, a delightful nine-year-old boy whose father does little but smoke hashish. Irfan sells ice creams from a rickety little cart filled with ice, as do many of the street kids of Jalalabad. This is how they help families survive.

I met Saludin, another ice cream boy. His dad is a polio victim who endures taunts of “dog” and “donkey” when he walks the streets begging on all fours.

There was Zabi, a lad with Hollywood looks who is certainly destined to become a filmmaker.

I met Steel, a boy of only nine or 10, whose hard and life-damaged face strikes fear into young and old. Steel heads a notorious Jalalabad gang and wields a razor, a knife or a syringe in order to extort money.

I met little Shazia, aged 11. Pretty as a princess, though dressed in rags, she is the devoted girlfriend of Steel. Shazia and Steel have vowed to marry. But only, says Shazia, if Steel gives up his gang and leads a better life. She doesn’t want to be married to a gangster – even one who declares he would die to protect her.

Steel, gang leader. From the documentary film Snow Monkey, by George Gittoes. Picture supplied by Gittoes.

So I didn’t actually meet these kids in Jalalabad. I’ve never even been to Jalalabad. But after watching George Gittoes’ new documentary film, Snow Monkey, at its Sydney premiere tonight at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, I feel as though I’d been right there with them.

In Snow Monkey, Gittoes tells the story of how he invited the kids into the Yellow House that he and partner Hellen Rose set up in Jalalabad in 2011 as a safe house of creativity for men, women and children. The Yellow House is full of music and art, and local people come here to learn acting and filmmaking.

In Snow Monkey, the daily survival struggle of the Jalalabad street kids is carved in high relief against the seething, crazy, dog-eat-dog life of Jalalabad. But humour is never far from Gittoes’ filmmaking, leavening those scenes which are truly grisly. The most challenging scenes in Snow Monkey, shot by Zabi who learned to use a cinecamera from Gittoes at the Yellow House, are of the sickening carnage caused by a suicide bomber who self-detonated outside the Kabul Bank in Jalalabad in April.

Snow Monkey is a tour de force by Gittoes, who received the Sydney Peace Prize last night (November 10, 2015). Receiving the prize from Lord Mayor Clover Moore, Gittoes spoke about his many decades as a witness to the atrocities inflicted by people against people. He also spoke about the resilient spirit which propels many war victims to rise above the truly shocking horrors visited on them by conflict.

Jalalabad ice cream boys (left to right) Irfan, Saludin and Zabi. Picture supplied by George Gittoes.

The Museum of Contemporary Art Australia is hosting free screenings of Snow Monkey, as well as some of Gittoes’ other documentary films. You would be doing yourself a favour if you, too, spend time and get to know the street kids of Jalalabad.

Elizabeth Fortescue, November 11, 2015, Sydney.

George Gittoes and the Sydney Peace Prize: an interview from Artwriter’s archives

Nov 8th

George Gittoes, 2014, photographed by Elizabeth Fortescue at Hazelhurst gallery, Gymea

The Australian artist George Gittoes will receive the prestigious Sydney Peace Prize on Tuesday November 10, 2015. It’s a high accolade that’s been won by the likes of Desmond Tutu.

Ahead of the Peace Prize ceremony at Sydney Town Hall that day, I wanted to devote a post to Gittoes and his extraordinary body of work.

I have delved into my archives and found a 1999 interview that I conducted with Gittoes at his then home base in Bundeena.

It is reproduced below, with some edits, as my small tribute to this amazing artist who is, typically, not planning the usual Peace Prize “lecture” but who has been busy making puppets for a performance that he, his partner Hellen Rose and a variety of dancers and helpers are planning to enliven the Town Hall on Tuesday night.

I hope you enjoy reading this 1999 interview. It came about because I was doing a story on Gittoes for the Daily Telegraph. He had just returned from Afghanistan, where he had focused on gathering stories from land-mine explosion survivors. It is interesting to note that this was 1999, two years before the events of September 11, 2001.

Gittoes: I tell you, I’ve never felt so much as if I was in an alien universe as I have just on this trip in Afghanistan. It’s unbelievable. It’s possible to spend a month in Afghanistan without ever seeing a woman’s face. It’s real apartheid for women. I’ve worked in South Africa where there was apartheid for the blacks, but at least blacks could more or less move around, but this is apartheid for women and it’s ten times worse than anything I’ve witnessed with blacks.

At the moment the Taliban are having the biggest war they’ve ever had. They’re using tanks and MIGs and it really is more extreme visually than Star Wars because, you know, they capture a tank and the Taliban cover it with Koran writing, and they’ve got these MIGs that are covered with blessings from the Koran. They captured them from the Russians 15 or 16 years ago and you’d see these turbaned guys that come up to work on a donkey and then they start working on the MIG and you think, well, gee, I wouldn’t like to be the pilot.

When I was in Afghanistan I lived with de-miners, the people who were getting rid of the mines. They’re all Afghans and former Mujahideen, they’re all soldiers, so that was a fantastic insight, to get into their whole history and psyche and way of life.

The Taliban have only been in power two years. The Koran says you’re not allowed to represent any living thing. That’s why you can’t take photographs. There’s also something in the Koran against music, so they’ve banned music. And now English and American nationals have been banned by the governments from going into Afghanistan. I was able to work there fairly well because a group of Australians have set up the whole de-mining thing and they’ve been there for 10 years, and the head of UNOCHA which is the UN de-mining is Ian Bullpit, and Ian’s been there for seven years, so Australians are about the only people who can safely move in Afghanistan. The Taliban respect them because they’ve organised this de-mining thing.

A painting by Gittoes of a soldier wearing night vision goggles.

Gittoes spoke about how land-mines are a scourge of many countries, not just Afghanistan:

I’ve been in Cambodia, I’ve been on the Thai-Burma border, and the Thai-Cambodian border, and I’ve been in the tribal belt of Pakistan and Afghanistan, and they’re just about the most mine-affected places in the world. Ian Bullpit was very happy to facilitate me getting into Afghanistan and working with all these mine victims.

The Taliban were happy for you to be there?

Only because I came under the flag of de-mining. About the only good thing that’s being done by the world for Afghanistan is the de-mining. Virtually all other aid has been pulled off. And I knew that this was a crucial time to be in Afghanistan because it was the anniversary of the rocket attack on Bin Laden where the Americans attacked Afghanistan. That’s why I organised to be in Afghanistan at that time. And I think the media’s losing touch with what’s happening in Afghanistan, and you can understand why. Basically they’ve had 20 years of war and the world’s tired of hearing about it. I’ve worked in every war-torn country in the world from Bosnia to Cambodia to Rwanda and Somalia and so on, and I’ve never seen such a totally destroyed country. The thing that pissed me off the most was there are two 2000 year old Buddhas, that are world famous, they’ve been studying them in art books since I was a kid, and they’re about 260 feet high or something, and I was trying to see them the other day and I discovered the reason why they’re being resistant was the Taliban have just recently been using them as target practice and destroyed them. I was furious. I said, you might be into Islamic religion and you might see them as Buddhism, but if you’d left them there it shows how Islam triumphed over Buddhism. And I said are they reparable? And they said oh no, the heads have been just blown to dust. And so the whole country’s been destroyed and there’s virtually nowhere for people to live, and all the ruins of the houses have been booby trapped with land mines and they’ve got unexploded artillery shells and so on.

Gittoes talked about some of the extraordinary stories he collected from land-mine victims in Afghanistan.

I went into the hospital in Kabul and it was like pre Florence Nightingale. The whole place was full of people who’d lost arms and legs and things to mines, and they were lying in there with flies all over them and no intravenous drips, and a lot of them were children. Because the children go playing in places where the parents wouldn’t be stupid enough to go. There was one father and son I met that had both been blown up and they’d both lost limbs, and the father had realised the son was out playing in a bad area, ran out and grabbed him, and as he grabbed him the son had hold of a trip wire so he pulled it and it got both of them. There’s one little boy I saw the other day who was riding a donkey and he had his brothers and father with him and they went over an anti-tank mine and it blew the donkey, the father and the two brothers completely to smithereens, and the boy had lost both legs. The mother was now looking after five daughters and him, in a country where there’s nothing, nowhere to sleep or go, and this was the brightest little kid, he’d taught himself English somehow, he was only 13 years old, and walking around on his arms. I’ve got a drawing of him walking on his hands.

Gittoes and his partner Hellen Rose, photographed by Elizabeth Fortescue in 2014 at Hazelhurst gallery in Gymea

I’ve decided just for a short time to narrow down to this mine thing, because for me it represents humankind at its absolute most insidious because these mines are designed to trick and trap other human beings and they’re done by engineers and scientists all over the world and they’re indiscriminate. And all the research in the world proves that only one of the people who gets hit by a mine in 20 is the intended target. So in a country like Afghanistan they’re only getting one soldier to 19 civilians. I’ve taken about 4000 photographs on this trip and I’ve personally interviewed hundreds of mine victims and so my own experience is in perfect alignment with what international statistics are saying. It just completely destroys lives. In most cases the people die. But those who survive, they’re around for a lifetime. And the worst cases I found were in the tribal belt of Pakistan where I was able to go and interview the women, and it seems pretty well the majority of people in a rural country who get hit by mines are women, and I’ve found this before in Mozambique and Cambodia and so on, because they’re the ones who work in the fields and who walk around for water and so on. In Pakistan I was able to go and see them. They’ve got the same rules as Afghanistan. The full burqa and not being able to see them and everything. But I got in deeper with the community in the tribal belt of Pakistan. But my contact there wasn’t through the de-miners, it was through the community itself. And so probably for the first time ever I was allowed to draw and photograph women. They’re even stricter than the Taliban. There’s one woman I can’t get out of my mind. She was lying on a stretcher sort of a thing, she had both legs blown off above the knee, she had one arm completely paralysed and she’d been blinded. In a wartorn place, covered in flies, and her children all around her, and her husband had been killed. She had six kids.

She could still talk. She said God only knows how we’re going to survive. And the kids were absolutely beautiful. The mine that had done that to her had killed her husband. And the kids, their whole universe was their mother. They were like precariously living in the shade of someone else’s verandah and the kids are still hovering around this woman who was blind, without legs and only one working arm.

In her case it happened four months ago, but she was still bleeding. All their savings had gone into, they had to pay for the hospital and the amputations. So the cost of being prevented from dying usually uses up all the resources they’ve got.

Gittoes at Werri Beach, November 2015, being photographed by Bob Barker for our story in the Daily Telegraph, Sydney

The most inspiring story I had was the people in the border area of this tribal area of Pakistan. There are more mine victims there than I’ve found anywhere else in the world and there’s no international aid agencies helping them. I was the first western person to visit it, ever. Everywhere I went was mined and there’s no de-miners, so I was constantly thinking when am I going to tread on one. One place they decided to get a whole lot of handicapped people (injured by land-mines) to come in and meet me. I was inundated. I had 40 or 50 people. And one old man just stuck out. And then I discovered that the woman he’d bought with him, he’d carried her for six hours. She had both legs missing. He’d carried her for six hours to meet me. He was 75 years old. He was the father in law. The husband was in Karachi trying to earn money to pay the debt that they owed the hospital for having to have her legs amputated. And she had six children. She said through a translator, she said I hate these mines and what they mean, I’m happy to devote the rest of my life to fighting against them. Now she’s agreed to be the ambassador for the handicapped in Pakistan and they’re going to raise the money within her village to send her to Rome where all the land-mine people are meeting.

A feature of Gittoes’ ability to manage his work in war-torn areas is that he makes friends with local people, follows their stories from year to year, and delights in seeing how many people can recover their lives even after they’ve been maimed by land-mines. Here, he speaks about one man called Ta Brang in Cambodia. He had lost his legs, but Gittoes returned to Cambodia to find him thriving.

Ta Brang, the man from (my picture) The Legless Bike, in 1993 he was living on the side of the road with his wife, and he’d lost both of his legs up his hips, and they had nothing, and he was just starting a bike repair business. And I went back to him now, six years later, he had a two week old new born baby in his arms. He’s now got five kids, he turned the bike repair business into a motorbike repair business, he’s built a nice house, and actually having no legs means it’s really easy working on motorbikes because he’s got access to them. I found that all the mine victims that I’d gotten to know and start to worry about in 1993, every one of them had made a huge amount of, you know, they’ve had more.

The blind guitarist of Angkor Wat, he’s the one that had been tortured by Pol Pot, he’s been reunited with his wife, she was in a refugee camp, he was being held as a prisoner, and so I met his wife. He’s getting on really well with his life, making money out of his music. He was a beggar in 1993 and couldn’t find his wife.

A lot of people say, are you depressed by what you see? But the fact that I’ve been doing this for so many years I’m able to see the turn-around. I just can’t express the inestimable pleasure in finding that these people had managed so well and were doing so well. The great thing was seeing Ta Brang with his two week old baby. He’s in Siem Reap.

Elizabeth Fortescue, November 8, 2015, Sydney

Yang Zhichao and the Chinese Bible: major new artwork for the Art Gallery of NSW

Jul 8th

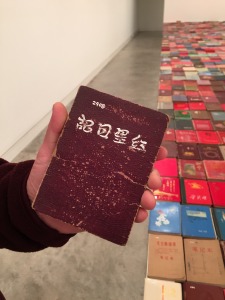

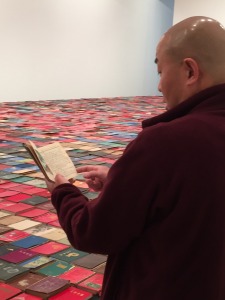

Yang Zhichao‘s artwork, Chinese Bible, on view at Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation (SCAF) in Sydney until August 1, 2015, is one of the most extraordinary works of contemporary art I have ever seen.

Now it belongs to the Art Gallery of NSW, thanks to its recent gifting by the Sherman family.

I saw Chinese Bible at SCAF and interviewed the artist with the help of interpreter and Chinese art authority Dr Claire Roberts.

My interview is reproduced below.

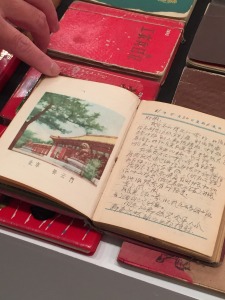

But first, a brief introduction. Chinese Bible, 2009, is a side-by-side display of 3000 personal diaries dating to China in the 50 years between 1949 and 1999. This period includes the years of the Cultural Revolution of 1966 to 1976.

“Private reflections were inherently dangerous in China during this period, with some decades more dangerous than others,” Gene Sherman writes in the Chinese Bible catalogue.

“As we know, the country focused exclusively on the collective at the expense of the individual.”

So, without further ado, here is my interview with Yang Zhichao.

Elizabeth Fortescue: What is the significance of these diaries and notebooks? Each one feels to me like a very important piece of history.

Yang Zhichao: There’s an important place in history for every diary that’s here, because of its connection to the individual and the individual’s connection to what was happening in China.

Were these ordinary, everyday people?

Yes.

Is it normal in China to carry a notebook around with you?

For some of these periods, the Cultural Revolution in particular, people were required to record things. You were required by your superiors in your work unit to carry your notebook.

At all times, or just at work?

Mainly at work, because from the 1950s onwards there were so many meetings. And they were meetings to disseminate politics and the directives from the Communist Party central committee. So writing down these directives was an important part of life. So that was a responsibility you had in the system.

Did people buy the notebooks, or were they distributed by authorities?

There are two instances. There’s the instance where the diaries were given out to people in the work unit as part of that expectation. But also people could buy them from shops. Of course in addition to writing down what was expected of them, people would make their own notations and carry these notebooks around so you do find a lot of different kinds of records in them, some of which reflect personal feelings or experiences.

You could be asked to reveal the contents of your notebook to your superiors?

During the early years of the Cultural Revolution in particular, people were required to offer up their diaries for superiors to look at.

This custom is no longer required?

This custom is no longer required?

No. By the early 1970s this kind of practice really had petered out. With the exception of people who had committed political errors in the eyes of the party. There was a continuing expectation that they would write self criticisms. Or that they would be forced to write confessions.

Did your parents have to keep notebooks like these?

Yes. Either they would carry it around or it would be in the drawer of their desk and they would use it as necessary.

Did people write little expressions of self that possibly they needed to disguise not to get into trouble?

The personal notations are very different from what we would think of as personal diary entries. What was regarded as a personal notation might have been something quite ordinary rather than a revealing diary quote.

I have been told that the recording of a little recipe might be seen as going against the regime?

The crucial thing is when that recipe was written — if it was in the middle of a major political campaign during the Cultural Revolution, and you were supposed to be recording political things and when you showed your diary for inspection it’s revealed that you’re thinking about (cooking), then your mind was not on the job. So you would have an ideological problem.

How do you think they all ended up in the markets for you to collect?

In Beijing in particular, where I collected most of the diaries, people value the written word and diary keeping. There’s an old custom in China that when you have items that you no longer need, you get rid of them. There are lots of people who go through unwanted things. These people come around all the time and they sort the different household waste into different categories and there’s a whole chain. Things then get funnelled into different avenues for resale or changing hands. And often a very small amount of money changes hands. It might be $1 or 20 cents. But for people living hard lives, it all adds up.

Is that what each of these diaries cost?

Sometimes things are just thrown out into the street, so people have just decided they want to dump stuff so there’s no direct monetary exchange. Someone just sees what’s there and goes through it. Basically these are valued for their paper so they’re sold according to their weight.

I interviewed Song Dong about his work at Carriageworks. Your work seems to resonate with Song Dong’s installation.

Song Dong’s mother is quite unusual in that she never threw anything away, but 90 per cent of Chinese households are continually getting rid of stuff they no longer need.

How much did you pay for the diaries?

The collection was put together 2005-2008. To begin with when I first discovered these notebooks they were very cheap. There were other people who might come to the markets and they might buy one. They might like the design of the cover. But no one was collecting them in a large scale until I expressed interest. Over time the traders got smart, so a notebook that had no content would be cheaper whereas one with notes in would be more expensive. Condition was another factor in deciding the price, and also size. So over the course of the three years I would have spent less than $10,000 Australian buying the diaries. Towards the end, if there was a particularly good diary, or now, a dealer might be wanting a couple of hundred for a diary because they’re sought after.

Have you read all the diaries yourself?

No, there are too many. But I’ve handled each one and looked through them all. I’ve read many of them but I couldn’t say I’ve read them all cover to cover.

Do you still collect these types of diaries?

I’m still very interested in diaries. If I come across particularly interesting diaries I will collect them, but this work is now complete.

It’s wonderful to have a work like this in Sydney.

To be perfectly frank, this material was all in second-hand markets. It’s not really taken that seriously in China. In a place like Australia it can be appreciated and studied.

Elizabeth Fortescue, July 8, 2015