Elizabeth Fortescue

Elizabeth Fortescue is the visual arts writer for the Daily Telegraph, Sydney, and Australian correspondent for The Art Newspaper, London

Homepage: http://www.artwriter.com.au

Posts by Elizabeth Fortescue

Sculpture at Scenic World, a great addition to Sydney art scene

May 12th

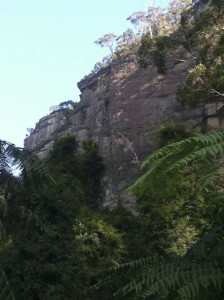

Sydney: A week or so back I spent a fabulous day in the rainforest of the floor of the majestic Jamison Valley in the Blue Mountains, where the event Sculpture at Scenic World had just been installed. You have until May 19, 2013, to see it and I highly recommend that you do. Here’s what I wrote about it for the Daily Telegraph.

Sydney: A week or so back I spent a fabulous day in the rainforest of the floor of the majestic Jamison Valley in the Blue Mountains, where the event Sculpture at Scenic World had just been installed. You have until May 19, 2013, to see it and I highly recommend that you do. Here’s what I wrote about it for the Daily Telegraph.

Sculpture at Scenic World, curated by Lizzy Marshall, is an annual art event which began only last year and comparisons with Sculpture by the Sea are inevitable.

Rather than starting out in the shadow of David Handley’s coastal art extravaganza, however, Sculpture at Scenic World has stepped out boldly and bravely with an air of confidence and professionalism.

It is a simply terrific show, and all involved must be praised including all the artists and curator Lizzy Marshall who also curated last year’s event.

This year, the works for Sculpture at Scenic World were selected by three judges.

Marshall curated the selected works into the spaces along the Scenic Walkways. Some works can be found in nooks and crannies, one is inside an old miner’s hut, some are draped over mossy boulders, many are suspended between giant trees in tiny, sunlit openings in the forest, and others are simply placed on the leaf litter.

Being in the forest and looking up at some of the sculptures, you catch a glimpse of the soaring peaks above you, and feel a bit like that wonderful scene in Picnic at Hanging Rock when the girls are heading off mystically into the unknown heights above them.

Marshall worked with an eco expert to ensure that the exhibition had zero ecological impact on the rainforest.

Here are some of the pictures I took on the day, although they hardly do the art works justice.

Elizabeth Fortescue, May 12, 2013

Sad death of Smudge, Archibald Prize dog

Apr 29th

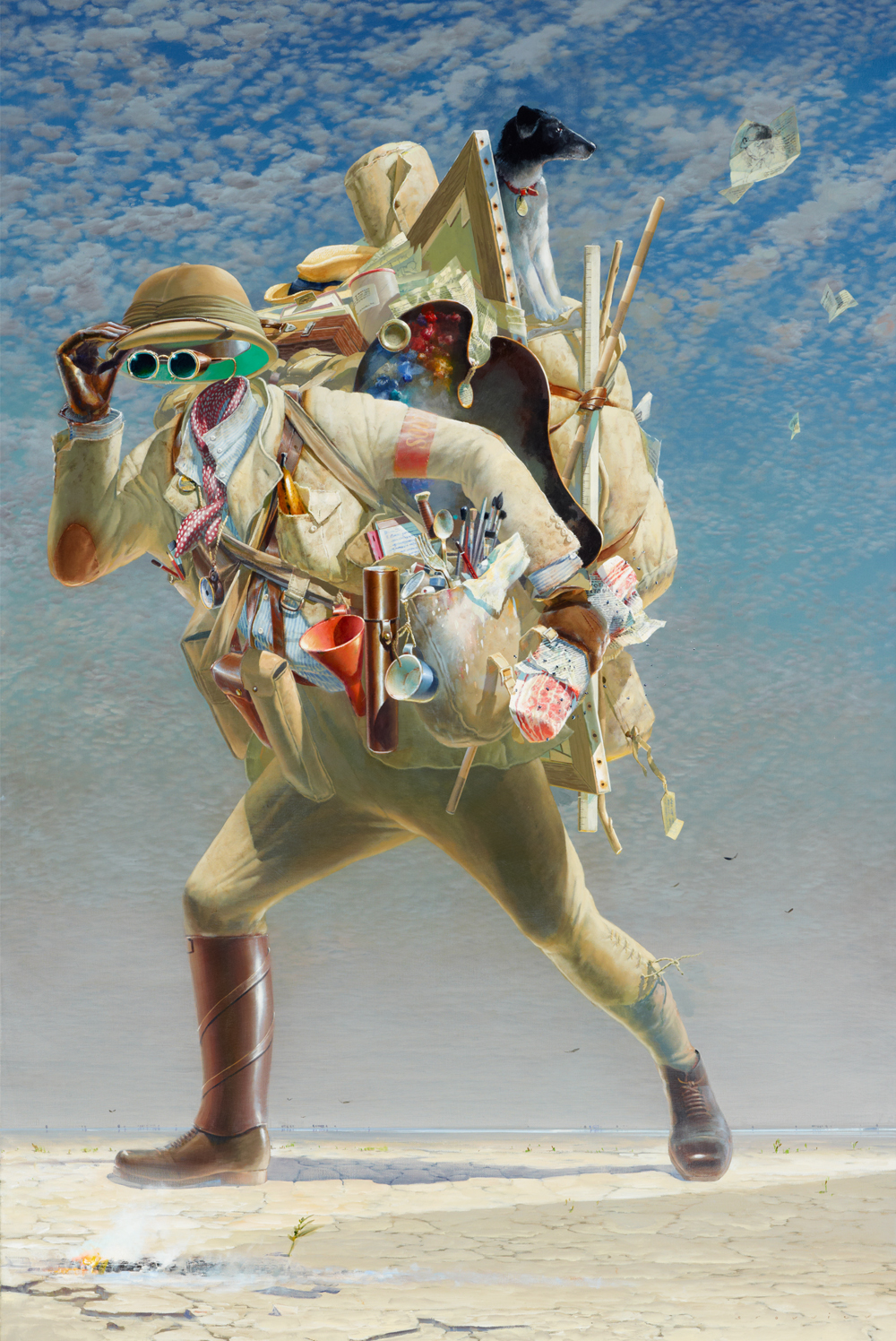

Artwriter was sad to learn of the recent death by snake-bite of Smudge, the little terrier which featured as one of the psychological trappings in Tim Storrier’s Archibald Prize-winning self portrait from 2012. The painting is titled The histrionic wayfarer (after Bosch).

Smudge was much loved by Storrier, who appreciated the dog’s lack of critical opinion in relation to his master’s work.

The dog accompanied Storrier faithfully in the studio, and was even allowed inside the Art Gallery of NSW for the gala announcement of the Archibald Prize when Storrier won.

According to Storrier’s wife Janet, it wasn’t the first time Smudge had been bitten by a snake. This time, it was fatal.

Knowing how much her husband would miss the dog, Janet had the animal stuffed. Janet sent me this picture of Smudge, who looks just as she did at the Archibald when she trotted nonchalantly into the AGNSW on the end of a horse’s lead-rein.

“Yes, it was so sad poor Smudge got bitten by a snake again and died,” Janet wrote to me.

“And photographed here (see below) with her is Trigger, Tim’s current companion who has had two snake bites this year, 10 days apart, which cost a fortune at the Bathurst vet who loves us!”

Here is Trigger, circling Smudge.

And here’s another one. Judging by Trigger’s tail, he’s trying to make friends with Smudge.

Here is Smudge in pride of place in her master’s studio:

And, finally, here is the painting in which Smudge appeared:

Hard-core dog lovers can read my original account of Smudge’s big day out at the Archibald in an earlier post on this website.

Elizabeth Fortescue, April 29, 2013

Nicholas Harding in conversation with ArtWriter about being in Paris

Apr 1st

Thanks so much to Nicholas Harding for this peek into his travels and adventures. I’ll bring you more information as he continues on his way.

Elizabeth Fortescue, April 1, 2013

Angels-Demons, an exhibition in Sydney by Russian artist collective AES+F

Feb 18th

If you were on Cockatoo Island for the Biennale of Sydney in 2010, you would have seen the extraordinary, gleaming piece of video art by the Russian artist collective known as AES+F. Titled The Feast of Trimalchio, the video was projected onto a 360-degree circular screen and was mesmerising and seductive, marked by some of the grand excesses of a 1950s Hollywood extravaganza about the Bible, complete with Charlton Heston in sandals and leather cuirass.

If you were on Cockatoo Island for the Biennale of Sydney in 2010, you would have seen the extraordinary, gleaming piece of video art by the Russian artist collective known as AES+F. Titled The Feast of Trimalchio, the video was projected onto a 360-degree circular screen and was mesmerising and seductive, marked by some of the grand excesses of a 1950s Hollywood extravaganza about the Bible, complete with Charlton Heston in sandals and leather cuirass.

Last week I interviewed Tatiana Arzamasova, the A from AES+F, at Anna Schwartz Gallery in Carriageworks, Sydney. Arzamasova was in Sydney to represent the rest of AES+F at the opening of their latest exhibition, titled Angels-Demons. I was doing a story for the Daily Telegraph, and you can read it here.

Angels-Demons comprises seven black, fibreglass statues resting on individual bright red plinths. Each statue depicts a huge baby either standing, sitting or crawling on all fours. The first thing that hits you is their gorgeous patina, a dazzlingly reflective surface which really does look quite devilish. Each baby sports a demonic tail, and several have nascent, webbed wings a bit like those of a fruit bat.

While these bouncing babies stand around two metres tall, they are based on AES+F’s original babies which were six metres tall. They premiered in 2009 in Lille3000, the French arts festival, where they were located outside.

Last week, Tatiana Arzamasova fussed over the seven babies at Anna Schwartz, getting their location within the gallery space just to her satisfaction. This involved much discussion with gallery owner Schwartz, and the going out and coming back in of both women in order to see each new placement with a fresh eye before deciding whether the arrangement was satisfactory.

Arzamasova directed a very patient young man with a hand-operated forklift device, who was shuttling the sculptures around on wooden palettes.

Once she was happy with the lay-out of the babies, Arzamasova and I went outside the gallery so she could smoke her ultra-thin Russian cigarettes while we talked. I mentioned that the babies and their anachronistically devilish features reminded me of the film Rosemary’s Baby, where Mia Farrow’s first-born is fathered by the Devil, and also the film Gremlins, where cute little furry critters turn out to be really very evil.

Once she was happy with the lay-out of the babies, Arzamasova and I went outside the gallery so she could smoke her ultra-thin Russian cigarettes while we talked. I mentioned that the babies and their anachronistically devilish features reminded me of the film Rosemary’s Baby, where Mia Farrow’s first-born is fathered by the Devil, and also the film Gremlins, where cute little furry critters turn out to be really very evil.

Arzamasova agreed.

“We love to play with cinema images and it has a lot of links to babies by Stanley Kubrik,” she said.

“First of all we created the concept that it will be not dangerous and not demons; that it will be babies without any European roots, without gender and with both symbols of goodness like wings and with the tails, in just one [body].

“They will grow up and the nature will take over. Because it’s really difficult to recognise the goodness and the evil especially when it’s symbols as image of a baby. It’s much more mystical and unpredictable than just an adult person.”

I asked whether she and the others in AES+F were standing by, wondering whether the world’s future were to be hopeful or bleak?

Arzamasova shrugs: “Like everybody,” she says.

“We just talk about the future in general. When we did the concept and first drawing, we talked about the idea of childish apocalypse.”

AES+F comprises Arzamasova and her husband Lev Evzovich, plus Evgeny Svyatsky and Vladimir Fridkes. The four artists, whose backgrounds encompass architecture and fashion photography among other disciplines, all gained a traditional grounding in the foundations of art in the Soviet era.

“Denis Diderot said, ‘don’t believe the architect who can’t draw,” Arzamasova said with a deep chuckle.

The way Arzamasova described it, the four work together every day in their shared studio in Moscow. Yes, they sometimes disagree on an artistic decision. But they work their way through their differences in order to collaborate in a very close way.

The way Arzamasova described it, the four work together every day in their shared studio in Moscow. Yes, they sometimes disagree on an artistic decision. But they work their way through their differences in order to collaborate in a very close way.

“We work as one artist with four bodies,” she said.

What about when they disagree? “Normally it’s a standard scandal. It’s true,” Arzamasova said, laughing. “And if you want to explain your position you should be tolerated. Normally sometimes we are really tough to each other, but it’s never going to destroy the group.”

Art Gallery of South Australia director Nick Mitzevich, who said he is “obsessed” with AES+F and has commissioned work by them, has been to their Moscow studio.

“It’s quite modest,” Mitzevich said. “It’s in one of those big high-rise buildings way out in the suburbs. It’s like the Communist state’s art studios. It’s full of lots of creative people. You catch this rickety lift up to their floor and it’s this very modest studio space. Their studio is full of Mac computers with huge screens. Lots of print outs and digital images. Tatiana and Lev’s family works on the production. There’s a sense of family that supports them. Their son supervises all their production.”

The studio is near the Vorobyovy Hills, the site of the last flight of the devil from Moscow in Mikhael Bulgakov’s novel, The Master and Margarita, Arzamasova said.

And speaking of the devil, the babies’ tails are a sign of our link to nature, Arzamasova said. “It’s also a sign of embryo development, because in development we are jumping all steps — to be fish, to be snake.”

Mitzevich said the AGSA purchased AES+F’s film work, Allegoria Sacra, last year. The work is currently on view at the gallery.

“I viewed the work half finished about a year and a half ago in Venice,” Mitzevich said. “We committed to buying the work and it made it possible for them to finish the work. These undertakings [of AES+F] are massive productions. This work was a really important work for us. It covers so many bases which our collection reveals. So many wonderful references to the chaos of the world we live in. And the work references the history of art and European religious art. We are very strong in both. It continues their obsession with mining the history of art and imagery. It’s a very important addition to the contemporary collection.”

A demon-baby appears in Allegoria Sacra, very similar to the ones now on view at Anna Schwartz. “They [AES+F] have worked in this form before,” Mitzevich said. “They continually go back to similar themes but they extract new ways of looking at things. This work [Angels-Demons] continues their complete irony and wit in their work. It’s a critique of the world we live in and it’s sometimes a bleak future, but it’s the irony and wit that gives it such a great currency and seduction.

“They are the first to admit that seducing the audience is something that’s important to them. They want to communicate their message to a wide audience.”

Elizabeth Fortescue, February 18, 2013

Toothpaste tubes and bird cages: photographs of Waste Not, by Song Dong

Feb 17th

Last week I visited the Song Dong exhibition, Waste Not, about which I have written previously (see my earlier post) and took some photographs which show the detail of this wonderful Chinese artist’s installation at Carriageworks, Sydney.

Last week I visited the Song Dong exhibition, Waste Not, about which I have written previously (see my earlier post) and took some photographs which show the detail of this wonderful Chinese artist’s installation at Carriageworks, Sydney.

It is strangely moving to walk quietly between the carefully laid-out groupings of hoarded objects, almost a sense of respect such as you might feel upon entering the home of a person who has just died.

A gallery staff member approached me to ask whether I liked the installation, and I told her I found it compelling. She told me something interesting. She said it was her own habit to throw things away rather than hoard them like Song Dong’s mother. When she told the artist that she never kept anything, he had looked at her sympathetically, sad for her that when she died her loved ones would be denied the chance to re-find her by sorting through the objects which had accompanied her through life.

I took these pictures, fascinated by the scale and detail of the work. I particularly like the picture at left, which shows a very sculptural stack of old wire bird cages.

The Japanese believe that objects take on a spirituality or presence, and this is far from alien to the western experience. If you want an example of this close to home, you have only to think of the recreation of a corner of Margaret Olley’s Paddington home at the Tweed River Art Gallery. The project, which you can read about if you click through, is a painstaking reconstruction of the artily cluttered environment in which Olley lived and by which she was continually inspired. To Olley, the vases of dying flowers were just as valuable as the vases of fresh ones. Perhaps Olley would have found much to interest her in Song Dong’s beautiful, empathetic art work. I like to imagine Olley and Song Dong’s mother together, conversing about their lives and the objects they loved.

Waste Not is on until March 17.

Elizabeth Fortescue, February 18, 2013