Elizabeth Fortescue

Elizabeth Fortescue is the visual arts writer for the Daily Telegraph, Sydney, and Australian correspondent for The Art Newspaper, London

Homepage: http://www.artwriter.com.au

Posts by Elizabeth Fortescue

Just downloaded: Sculpture at Sawmillers, McMahons Point, Sydney

Sep 19th

Sculpture at Sawmillers is a new event in the Sydney art calendar, and hopefully it will become a regular one.

Organised by former National Trust CEO Elsa Atkin, Sculpture at Sawmillers is a fabulous event. It took place this weekend (September 18 and 19, 2010) at Sawmiller Reserve in McMahons Point, on Sydney’s lower North Shore.

I went along yesterday when the sun was shining down, the harbour sparkled, and families were out with their kids and dogs, checking out the 53 sculptures dotted throughout the park. Even the Scouts were there, selling home-made lemonade and stoking up the sausage sizzle. It all felt very democratic and happy.

The sculptures were selected for exhibition by prominent curators Jane Watters and Nick Vickers, and sculptor Michael Snape. They did a brilliant job, choosing a range of artists including some of our very best known to others who are still making a name. The photographs below will give some idea of the quality and interest of the works on show. There was even an artwork attached like a figurehead to the picturesque and rusty old wreck in the bay.

You could describe Sculpture at Sawmillers as a tempting aperitif to Sculpture by the Sea, the outdoor exhibition of sculptures which occurs each year along the coastal track from Bondi to Tamarama. It opens next month. But this would be to understate what an imaginative and artistically successful venture Sawmillers was. Let’s just wish Elsa Atkin and her team a bright future, so artists can use Sawmiller Reserve as their playground every year.

Elizabeth Fortescue, September 19, 2010

Edward Horne Title: Think Tank Dimensions: 200 x 220 x 440cm Materials: Steel, filing cabinets, hole punchers, paper dispenser etc...

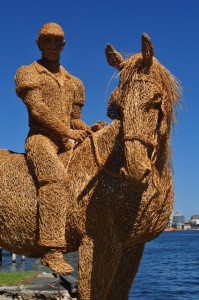

Belinda Villani Title: Tribute to a Workhorse Dimensions: 2.7 (h) x 2.7 (l) x 1(w) m Materials: woven and treated rattan and zinc plated steel

Peter Kingston Title: Popeye Chess Set Dimensions: Board: 128 sq cm, 32 pieces ranging - 14-40 cm Materials: figures cast in bronze, board timber

Geoff Harvey Title: The Sawmillers Factory Dimensions:160 x 130 x 65cm Materials: Found objects, wooden patterns, wood and metal

Harrie Fasher Title: “Traces of Memory” Dimensions: Horse: 2500 x1000 x 2000cm, Dimensions: Cages - various Materials: Steel, found objects,rope

Bjorn Godwin Title: Figurehead Dimensions: 130 (h) x 40 (w) x 40 (d) cm Materials: Fiberglass, polyester resin, mixed media (at rear in water, Sawmiller's worm, by Gary Deirmendjian)

Linda Klarfeld Title: The Chairman Dimensions: 140 x 100 x 150 cm Materials: Resin with metal finishes

Will Coles Title: Obsolescence Dimensions: approx. 55 x 50 x 50cm Materials: Cast cement (limited edition of 10)

Judit Shead Title: Spring Dimensions: 62 x 33 x 33cm Materials: Cast bronze

Peter ‘Beatle’ Collins Title: Wave out of Water Dimensions: 5.5 x 1.6 x 2m high Materials: Steel concrete, mesh, sticks

Vince Vozzo Title: Mama murders Dada with a chess piece Dimensions: 149 x 108 x 26cm Materials: Bronze and timber

Just in: Pictures of Peter Kingston’s Toast-rack tram

Sep 17th

Peter Kingston has just sent me these images of one of his artworks. The piece is a quaint and nostalgic toast-rack tram, heading for Bondi with a smattering of cartoon and real-life characters on board.

Peter has long been a champion for the retention of Sydney’s architectural and maritime history. As such, he is a lover of the trams which once rumbled up and down the city’s main streets and took thousands of commuters in and out of the suburbs.

Here, he has recreated one of the trams in all its glory.

“It lights up and contains Sydney eccentrics – Bea Miles, Mr Eternity, Ginger Meggs and his monkey, the White Man, the Trolley Man, Boofhead and the little Fan Man,” Peter said.

Please enjoy these pictures.

Elizabeth Fortescue, September 17, 2010

New Charles Blackman Photographs, exclusive to Artwriter

Sep 15th

These rare photographs of Charles Blackman and his first wife, Barbara Blackman, were sent to me this week by their son Auguste Blackman, who gave me permission to publish them on my website.

The photographs were taken by Auguste at the Blackman Hotel in Melbourne this month, the day after the hotel’s official opening at which Charles, 82, had been the star attraction.

The photographs show Charles and Barbara sharing breakfast in the hotel.

One of the pictures shows Charles Blackman with his daughter Bertie Blackman.

My thanks to Auguste for permission to use these delightful and intimate family snapshots.

Elizabeth Fortescue, September 15, 2010

Peter Kingston Interview

Sep 12th

Peter Kingston shows Sawmillers curator Elsa Atkin one of his chess sets

This week I interviewed Peter Kingston at his home on the Lower North Shore. Peter was putting the finishing touches to his work for the inaugural Sculpture at Sawmillers exhibition, taking place on September 18 and 19 at Sawmillers Reserve, McMahons Point.

Peter is one of Sydney’s best-known artists, who exhibits at Australian Galleries in Paddington. He cares deeply about Sydney’s built history, and has gone in to bat for the Walsh Bay wharves, prior to their redevelopment, and particularly for the little wooden ferries that plied the Circular Quay-Lavender Bay run.

Peter’s home is perched above Sydney Harbour and resembles, in its ramshackle charm, some of Peter’s drawings of Pittwater boat houses and the like.

The first thing you see when you enter is a giant and ancient glass-fronted cabinet, filled with Luna Park memorabilia. Peter was working with other artists including Martin Sharp on the redesign of Luna Park at the time of the tragic ghost train fire in 1979, which claimed the lives of six children and one adult. The fire has deeply affected the artists involved with Luna Park at the time of the tragedy. All sorts of theories have been proposed to explain the advent of the fire, but Peter said he likes to believe it wasn’t deliberately lit. The artefacts in Peter’s cabinet are poignant reminders of the night when flames roared into the sky and innocence perished.

Also near the front door are half a dozen newspaper cuttings featuring photographs of the Governor General Quentin Bryce, whom Peter admires very much. The Governor General is going to open the Sculpture at Sawmillers exhibition, in which 53 artists will exhibit, on the Saturday afternoon.

Peter takes me downstairs into one of his studios and shows me several of the wonderful chess sets which he has created. These are about three times the size of your standard chess set and consist of chess pieces made from plasticine and cast in bronze. He has hand-painted the chess boards, decorating them with pictures of the characters he has used as chess pieces.

The first chess set Peter showed me was his Luna Park chess set. Peter had made laughing clowns to be used as pawns, while Coney Island, dodgem cars and other amusement park objects took the place of the other chess pieces.

Next up was Peter’s Popeye chess set. At one end, Popeye was the king and Olive Oyl his queen. At the other end, Brutus and the Sea Hag were king and queen.

“This has been 20 years in the making,” Peter said of his Popeye chess set.

He recently had the chess pieces cast in bronze, especially for the Sculpture at Sawmillers show.

The final chess set was the Aussie Comic Chess Set featuring the Magic Pudding, Snugglepot and Cuddlepie, Ginger Meggs and Minnie Peters, and Blinky Bill, among others.

“It’s still under construction,” Peter told us.

One of Peter’s other assemblages was an old Sydney tram whose passengers were real-life characters from early Sydney. The formidale Bea Miles sat on one of the benches, no doubt quoting Shakespeare. Rosaleen Norton, the “witch of Kings Cross”, was also on board. And hanging off the side was “the fan man”, who Peter said was another colourful person from Sydney’s past. Peter loves the old trams, and has paid homage to them in this work.

“It’s a toast rack tram and it’s the most beautiful thing,” Peter said.

Finally, we noticed a green wooden assemblage mounted on the wall. This one, Peter told me, was made for his last exhibition. Nobody bought it. It’s the Luna Park ghost train, and represents the first time that Peter has tackled the awful topic so directly in his art. You can turn a little handle and see the ghost train cars rattle by, each one with a witch on board. It’s like Luna Park is closed, and all the characters in the rides have come out to play, Peter said.

It’s a eerie piece, and perhaps it’s no wonder that no one bought it. The ghost train fire is a part of Sydney’s history that few people like to reminded of, but one that Peter and Martin Sharp have vowed to keep alive in the public mind.

Stephen Vitiello Interview

Aug 24th

August 2010

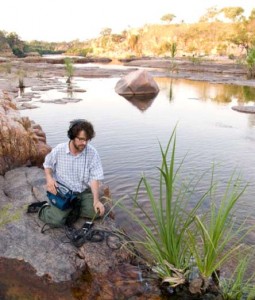

If you visit Sydney Park in St Peters any time before September 12, 2010, be sure to have a look at the artwork by Stephen Vitiello. Or should that be “listen” to the artwork, for Vitiello is an American sound artist and the auditory realm is his artistic home. The title of this work is The Sound of Red Earth.

Vitiello, who incidentally had a six-month residency on the 91st floor of the World Trade Centre in 1999, came to Australia recently to record the sounds, rather than the sights, of the remote Kimberley region of Western Australia.

It was the Sydney contemporary art philanthropist John Kaldor who invited Vitiello to Australia, and in accepting Kaldor’s invitation Vitiello became the 20th Kaldor Public Art Project. (See the others, and future projects, at www.kaldorartprojects.org.au)

The day before Vitiello’s work went on show to the public in August 2010, I went to Sydney Park to interview him for the Daily Telegraph. A brisk wind was blowing and it was a relief to walk into one of the three “galleries” housing his work. These pop-up galleries were the three former brick kilns which once made bricks for much of Sydney’s early housing.

In the first of these kilns, the first thing I noticed was the rich red soil brought in from the Kimberley area for the exhibition. The soil was thickly spread all over the floor of the kiln, and it left satisfyingly crisp tracks when you walked on it. Red lights mounted around the lower walls of the kiln accentuated the gorgeous colour of the soil. This kiln was devoted to the sounds of the birds which Vitiello recorded in the early morning or evening when they were most active.

Punctuating the lighter, gentler chirpings that made up most of the recording was the occasional harsh “crawk” of the crow which Vitiello seemed to find watching him wherever he went. Vitiello wasn’t sure what species of birds he recorded, apart from the obvious and ubiquitous crow, but he was attracted by the suggestion that he could invite an ornithologist to identify them.

On to the second kiln, where green lights played on white sand. This kiln was water-themed, and the sounds were of tinkling, bubbling and rushing water.

The third and final kiln, featuring a pinky grey light, was devoted to the sounds of the wind.

“Sound is very much part of contemporary art today, and I always want to bring to Australia what is the latest development in contemporary art,” Kaldor told me.

“I love very much the Kimberley area. It’s only when you’re up there that you really see the grandeur of Australia, the vastness, the open spaces. It sounds trite, it sounds like an ad, but that’s what it is. And the light is different and the sound is different. The Australian landscape has been painted since colonial days by the white people and by the Aborigines since forever. But very little has been done about sound. And I thought it would be great to record the sound of the Australian landscape. And that’s what Stephen’s done. He’s been up there twice for a week, recording different sounds. And this is the result of it. I wanted an international artist but to do something very Australian.”

Kaldor was pleased that, at time of writing, Vitiello was also showing an artwork at New York’s High Line (www.thehighline.org). For that work, Vitiello recorded all kinds of bells in New York – the New York Stock Exchange bell, school bells, the UN Peace Bell and even dinner bells.

“So we really live in a most global world,” Kaldor said.

Stephen was a somewhat intense and focused person, although delightful to talk to. He said Kaldor had been generous in allowing him free rein with his project.

In traversing the vast distances of the Kimberley, Vitiello was guided by a local art gallery owner.

“I had a guide and I was really at his mercy,” Vitiello said.

“The more things would go well, the more he got a sense of what appealed to me. Most people don’t think of sound first. He knows the Kimberley very well, but he’s not a sound tracker or sound guide out there.

“The first trip was driving; the second was on the water. We drove four or five hours a day, then we’d set up camp. I’d wake up before the sunrise and start recording. You’d capture that excitement when the frogs are fading out and the birds are waking up.”

But isn’t the Kimberley – so far from the big cities – very silent?

“No, it isn’t,” Vitiello said. “It often happens to me as a sound artist. Poeple take me some place and they say ‘you’ll really love it, it’s quiet’. But you get there and it’s not quiet at all.”

I suggested that an ornithologist might help him to map the bird-songs in the piece, identifying which birds could be heard. Vitiello was interested, and said he was actually part of a nature recorders’ community on-line. But this type of specificity wasn’t really for him.

“For me it’s much more about the texture, experience and memory than it is about that,” he said. “Although it would be great to have a sound map of what you’re hearing.”

Vitiello discussed his thoughts about sound, as opposed to the visual sense with which most of us primarily explore the world.

“We’re all deeply affected by sound, we just don’t always talk about it or think about it,” he said. “And we’re definitely affected emotionally by sound in a way that’s different than the way we are by a picture. We look at things and we process it intellectually and we say ‘oh, isn’t that a lovely framing of light coming through?’, but it’s very different from the way a sound hits your gut or your skin and it’s also very individual. I feel like sound is much more open. It’s very generous in the way that it allows different types of interpretation.”

Vitiello’s best-known sound artwork resulted from his six-month residency inside the World Trade Centre, which was destroyed in the 2001 attacks on New York.

“The idea was artists were given these studios to use and ultimately my project became about listening to the building itself,” he said.

“I captured the sound of the building moving, creaking and cracking, planes going by, helicopters, storms. You couldn’t open the windows so I learned to use these contact microphones that worked like a stethoscope.”

Vitiello made one of his WTC recordings on the morning after a hurricane had passed through.

“It was safe to go in, but you could really feel the sway. I felt like you couldn’t feel it until you could hear it. One’s perception opened up once you could hear it.”

The WTC recording eventually presented him with a moral burden, given that it took on such a poignant historical meaning following the September 11 devastation. Almost reluctantly, he played his recording to other artists who had experienced a WTC residency, and they encouraged him to do something important with his ethereal “memory of the building”.

The Whitney Museum of American Art invited Vitiello to exhibit his WTC recordings in the 2002 Biennale, which he did, and it later purchased a copy.

Vitiello retains the original, “and I keep responsibility for archiving it”.

Vitiello lives in Richmond, Virginia, where he teaches.