Elizabeth Fortescue

Elizabeth Fortescue is the visual arts writer for the Daily Telegraph, Sydney, and Australian correspondent for The Art Newspaper, London

Homepage: http://www.artwriter.com.au

Posts by Elizabeth Fortescue

Artwriter Interviews Rafael Lozano-Hemmer

Dec 17th

I interviewed Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, the Mexican-Canadian artist, on December 1, 2011, in relation to the exhibition of his work, Recorders: Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, which has just opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art. Lozano-Hemmer is fascinated by the technology of modern surveillance. But, for him, surveillance is not sinister. It’s just part of daily life. And he believes it’s time artists took the technology and made something poetic or strange from it. It was a fascinating interview. Here’s the edited text.

Do you have a scientific background as well as being an artist?

Yeah, I do. I have a degree in chemistry. So the nerdiness goes deep.

At what point did you decide you were also an artist?

It was kind of always there. My family were nightclub owners and they were always surrounded by musicians and artists and poets. I guess at university I started working a lot with people in the theatre, so it was actors and choreographers and writers and composers, and that’s when I decided, yeah, this is what I want to pursue.

You blended the two quite early on?

Yeah, I actually graduated from chemistry. I worked in a chemical lab for about five months or something, and then I just realised that I’m still passionate about science. I believe science can be intensely creative and uncertain and exciting and so on, but most of the excitment in science in terms of research happens only after you’ve done a doctorate and a post doc and if you’re lucky you have your own lab. At my level of chemistry it was all very much analysis, it was not very exciting. Whereas with performing arts and then visual art, I always felt there was an ongoing challenge and it was much more exciting. So I’ve forgotten most of my chemistry. The other day I found my thesis and I said ‘I wrote this?’ I couldn’t believe it. I didn’t know what I was saying. That’s what happens when you don’t practise.

You were involved in performance art before visual art?

Yeah, totally. I was involved in performance art, radio, experimental sound art, before I entered the visual arts. Most of my first pieces, like Surface Tension from 1992, is a large eye which follows the public wherever they go. When we first did that it was staging for a contemporary dance performance where the dancers would control all their lighting projections and sound through the use of sensors. People would think those dancers were choreographed to match the pre-recorded eye, and it was only at the end of the performance where we would welcome the public to try out for themselves the interactive modules that they would realise that eye did actually follow you wherever you went. That sense of the public being the actor, or the public activating the piece, is what led me to the visual arts. That piece later became a stand-alone projection that would sit in a museum and would pursue anyone who walked around.

I love the intersection between science and art, and politics and art. Talk about how monitored we are. How do people respond to that?

It depends very much on the person and the piece. Some pieces are much more predatorial and dark and ominous, and some pieces are much more connective. With most of my work I’m trying to underline the fact that that kind of moralistic or idealistic approach to computer survellances is misplaced. This is not like the threat of something which will happen in the future, or some kind of Orwellian tale of control and so on. We live in a society that is now completely functioning through those mechanisms of control, and we have been for a very long time. Globalisation is itself throughout the economy, politics, everything, is based on the idea of metrics, of tracking. Credit cards build an entire data bases of who we are, where we buy, what we buy, when we buy it, and so on. Whether you’re a painter or not, the fact is your public watches eight hours of screen time a day. So we live in that technological culture. Thse kinds of cameras or surveillance mechanisms are at work at all levels. I think the challenge for artists is then to misuse these technologies to create poetic or critical or otherwise creative connective experiences which bring people together. Whenever people emphasise that dark side, I try to say ‘this is at work already’. In every museum you are tracked like this. But at the same time the opposite end of the spectrum is when people think of these works just as playful, fun, as something that is quite infantile. And while that’s also fine as an interpretation, I think it’s between these two extremes of Orwellian, dark, menacing reality, and this playful, gadgety, technological, inclusion thing, there is a whole range of different experiences which can be expressed that are along the lines of what art has always done. Like thinking about absence and presence and loss and love and connection and hormones and betrayal and alterity and otherness, more like the bigger questions. And I do think that more and more, artists are being able to explore that big spectrum of possibilities with these tools instead of going for these very common interpretations of the state of technology today.

It’s a bit like David Hockney and his use of the iPhone to make drawings. He’s grasped technology, too.

Totally. I’m actually really happy that you mention him. Because he’s an example of a contemporary living artist who has embraced these technologies in his expression of his craft. I come perhaps from the other side, from the side of engineering and science and so on. But this is also part of culture, and this is also forming part of our contemporary reality. So for me it’s interesting to separate myself from this idea of new media. You know how oftentimes people talk about “new media”? I really dislike this term because there’s nothing new about what I’m doing. We’re still talking about this stuff as though they were still new or live or original, and I find it way more interesting to make connections to the past and see ways in which my work can be related to other experiments that have already been taking place for almost 100 years, than to pretend that what I’m doing is new, than people think that the novelty of it is these devices. It isn’t. My contribution has to do more with the traditions of experimentation.

There’s a work in your exhibition which is called The Year’s Midnight, where the viewer’s image becomes obscured by plumes of smoke that emanate from the eyes in real time. It’s creepy and deathly.

(He laughs). It’s inspired by representations of St Lucy in western art. St Lucy pulled out her eyes from her orbits and handed them in a little tray to her pagan admirer who wanted to marry her and who was always praising her eyes, and she said ‘if you want my eyes, here they are, I am going to belong to God’. [The work] finds your eyeballs with face recognition, it extracts your eyeballs and it puts them on the lower left. But it also records them. So on the bottom of the display you see the eyes of everybody who’s looked at this work before . And then out of your empty sockets comes the enveloping smoke. I don’t exactly have a prescriptive reason why that happens, but it quite perverse and dark. It’s about observation. Who is the observer and who is the observed. The status of vision in a museum. This show has something like 20 or 30 different cameras that are tracking the public so in a way the camera is this eyeball. Just a little bit of an experiment about our expectations of what a painting is or an artwork is.

It made me think of human cremation.

Totally. And if you pay attention to the detail of the smoke, the smoke is actually being generated live. It’s not a pre-recorded video that just loops, it actually is the mathematics of how smoke spreads in a room, and applied live. It’s mathematically quite complex, so I’m kind of nerdily proud of that side of that project.

All the data you collect during your exhibitions, is it stored or thrown away after the exhibition?

It just accumulates until we run out of disc space in the computers. So for example the project microphones will keep the voices of up to 600,000 different participants, and then it will just, as one more participant goes, then the very oldest recording then gets erased. So it’s a constantly changing repository of about 600,000 voices

All of the pieces are memento moris. It reminds us of our fleeting existence on earth or whatever. Something like that.

Colours will influence work?

Totally. There is a project called People on People which is the mother of all surveillance devices. 11 computers track the public and record them and then play them back into the future. So if a school of uniformed children come to see the show, they will be recorded with those uniforms. And in the future if you walk into the room you may walk into a room that is very much teeming with children dressed in that uniform. Somebody was asking me if it’s possible to resist this surveillance. Well, one thing you could do is not go to the show. The other way to do it is to wear disguises.

But this show is really as good as people end up doing in it. It’s not like I need people to perform or wahtever. Some pieces benefit from that. But I’m hoping that it’s going to be interesting for people even if they’re not performing. Just looking is a way of participating.

Elizabeth Fortescue, December 17, 2011

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer media preview, MCA Sydney

Dec 16th

Ever get the feeling you’re being watched?

Ever get the feeling you’re being watched?

You certainly will at the MCA’s new exhibition, Recorders: Rafael Lozano-Hemmer. All of the one dozen works on show are tracking, measuring, surveillance and recording devices, writ large.

Artwriter attended the media preview of the exhibition this week, and took the photographs included in this post. The picture at left is Lozano-Hemmer.

I will upload my interview with Lozano-Hemmer soon. These pictures, however, will give some idea of the extraordinary artworks in the show.

Lozano-Hemmer was a personable, warm, and rather funny narrator of his own works.

Here, then, are some of my pictures.

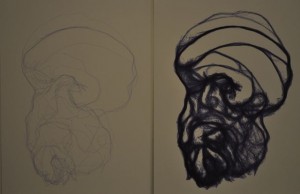

This is a detail of one element of a larger work titled Seismoscope.

This is a detail of one element of a larger work titled Seismoscope.

Seismoscope is a highly sensitive device which detects movement in the surrounding area, and records it by automatically drawing the face of a philosopher. Lozano-Hemmer can set it up to draw other things, as well. On days when there is little activity in the museum, Seismoscope draws a very light image. On days when the builders are working hard on the new MCA wing, and there are lots of vibrations, the image will be bolder and darker. You can see this effect in the image at left.

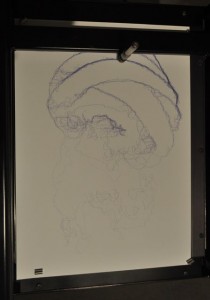

This is a wider angle view of the same thing.

This is a wider angle view of the same thing.

This is a close-up of that day’s drawing being drawn. You can see the pen at the top of the page. It is programmed to draw the philosopher’s face in bold, strong lines when there is a lot of vibration, or to produce a very light drawing if the surroundings are quiet and still.

This mesmerising work, at left, is a line of measuring tapes which detect the presence of a viewer in front of them. When one of the tapes picks you up, the tape will continue to slowly grow until its full extent is realised and the top-heavy measuring tape crashes to the floor.

This mesmerising work, at left, is a line of measuring tapes which detect the presence of a viewer in front of them. When one of the tapes picks you up, the tape will continue to slowly grow until its full extent is realised and the top-heavy measuring tape crashes to the floor.

Artwriter testing a Lozano-Hemmer artwork called The Year’s Midnight.

Artwriter testing a Lozano-Hemmer artwork called The Year’s Midnight.

A camera is mounted above the mirror in which you see yourself. You look up into the small camera, and by using face-recognition technology, the work removes your eyes digitally and puts them at the bottom of the screen in the manner of St Lucy in Mexico. Smoke then emanates digitally from your eyeballs.

And here is Artwriter in a fascinating work called People on People. Once detected, you appear randomly on a huge screen. Ghost images of other visitors to have stood in front of the work appear of their own volition. Time slips. People who were recorded many months ago appear on the same screen beside people who have only just left their “impression” on the work.

And here is Artwriter in a fascinating work called People on People. Once detected, you appear randomly on a huge screen. Ghost images of other visitors to have stood in front of the work appear of their own volition. Time slips. People who were recorded many months ago appear on the same screen beside people who have only just left their “impression” on the work.

I will write my interview with Rafael Lozano-Hemmer and post it on these pages soon.

Elizabeth Fortescue, December 16, 2011

Picasso in Sydney: ArtWriter goes behind the scenes

Nov 13th

Picasso: Masterpieces from the Musee National Picasso, Paris, is on at the Art Gallery of NSW from this weekend.

Last week, I went behind the scenes to do a video for the Daily Telegraph on just how Sydney came to be seeing 150 works by such a great master as Pablo Picasso.

Elizabeth Fortescue

Picasso in Sydney as seen by ArtWriter using helmet cam!!!

Nov 13th

I did this video with editor Ian Perry for the Daily Telegraph. It was hysterically funny to do, because it involved going around the Picasso exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW while wearing a Go Pro camera mounted on a helmet. Check it out. It will give you a rather quirky idea of what the new exhibition, which is on until March 2012, is like.

http://video.dailytelegraph.com.au/2166243087/Sydneys-Picasso-exhibition

Elizabeth Fortescue, November 13, 2011

Tim Silver stares into his own grave – and so can we

Oct 4th

Tim Silver is a young Sydney artist whose current show (Everything in its right place, at Breenspace until October 8, 2011) is utterly hypnotic, dealing as it does with human decay and decomposition. For this exhibition, Silver created busts of his own head and shoulders – not out of bronze or marble, but out of home handyman materials such as putty or wood filler. He allowed the busts to degrade naturally over time, photographing them them to document the stages of their decline.

Tim Silver is a young Sydney artist whose current show (Everything in its right place, at Breenspace until October 8, 2011) is utterly hypnotic, dealing as it does with human decay and decomposition. For this exhibition, Silver created busts of his own head and shoulders – not out of bronze or marble, but out of home handyman materials such as putty or wood filler. He allowed the busts to degrade naturally over time, photographing them them to document the stages of their decline.

The resulting work is like fast-tracking the process by which youth becomes age and finally death. It’s as though Silver has stared into his own grave and marked the various stages of his return to the earth.

Depending on the material Silver has used to create them, the busts sag, crumble, wrinkle, and even sweat. It takes them perhaps three or four weeks to stabilise and solidify, because they have no armature to support them and they are not hollow. They are made of solid putty or wood filler.

The work at left is one of the busts. It is titled Untitled (bust) (Mahogany Timbermate Woodfiller), and was completed this year. The accompanying series of photographs (see below) shows the bust cracking, its various pieces drifting apart, the jaw hanging loose. The bust could well continue to crumble after it has been purchased, a fact which causes Silver to merely shrug.

You can’t help getting up close to these photographs, peering at them in the way you peer at photographs of Egyptian mummies or the freakishly well-preserved bodies of prehistoric ancestors such as Oetzi the Iceman. It is fascinating to look at these ancient people and imagine the vast period of time between them and us, to contemplate the shared impulses and feelings we would have, and ponder the nature of their lives and deaths. Speaking of Oetzi, it is intriguing to notice that many of Silver’s busts begin their devolution covered in a light layer of ice. This is due to the fact that the busts are frozen to make them easier to remove from their moulds.

Here, then, is my interview with Tim Silver, which took place in the exhibition space.

ArtWriter asked Silver to speak generally about the process of making the busts.

ArtWriter asked Silver to speak generally about the process of making the busts.

Tim Silver: Each one’s a unique mould. Different wood putties that you can get, all commercially available from the cheaper putty which is mahogany and pine to the Selleys linseed oil based putty which develops a leathery skin and really wrinkles up, through to the traditional Spakfilla. I freeze it so it can be de-moulded. The mould’s destroyed in that process. And they’re set up in a studio environment and documented. So it’s just the putty reacting to atmospheric conditions.

You haven’t had to apply heat or anything to them?

No, it’s just the chemistry of weight and atmospheric conditions. Because there’s no skeletal form inside of them, that’s why they sag and do that kind of thing. It’s just gravity.

How long does it take until they harden?

Each one takes three to four weeks. (Silver said he completed the project in his Redfern studio, taking up to 100 images of each particular bust. From those, he makes his selection of up to six photographs per bust.)

When do you decide to stop?

Ultimately the works do stabilise. The Timbermate one really dries out, so it sort of resembles plaster once it’s dried out. So there’s a nice tension between the sturdiness and the fragility there.

Am I right that one of the busts is in the Blake Prize at the moment?

Yes, not one that’s exhibited here, another version.

You take the moulds of your own face?

I’ve been working with a life caster called Keith Rae (in Leichhardt). He does the original life casts for me. From that I go away and I dress it with a hoodie and I make my own moulds from that.

Does it feel creepy to have a mould made of your head?

Does it feel creepy to have a mould made of your head?

Yeah, yeah, it’s like being buried alive.

Quite claustrophobic?

Yes. Obviously when I work with Keith there’s a lot of discussion and coaching.

Were you scared the first time you did it?

I’ve had it done to me before. I’ve been a model for an artist called Stephen Birch who is no longer with us. He was very good to me. He taught me the casting skills which I work with now. His first dabbles in life casting were on me. He was very supportive and helpful.

A lot of your work undergoes degradation or transformation. Why?

One part of me is interested in the idea of a non-static art object. I look at these things [the busts] as performative objects. [I like] the idea of creating art that participates in the world rather than something that is static.

Apart from Birch, who are your other influences?

I’m very interested in Hany Armanious‘ work and people like Mikala Dwyer and obviously my supervisor at COFA [who] was Lyn Roberts-Goodwin.

Elizabeth Fortescue, October 4, 2011