Bernard Ollis: an artist’s insight

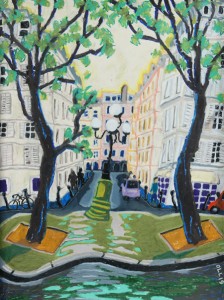

Bernard Ollis‘s latest exhibition, Paris Considered, was recently on show at NG Art Gallery in Chippendale. I had the pleasure of opening the exhibition.

Bernard Ollis‘s latest exhibition, Paris Considered, was recently on show at NG Art Gallery in Chippendale. I had the pleasure of opening the exhibition.

I thought the time was ripe to post a transcript of my first ever interview with Bernard. There have been many since then, and Bernard and I have become firm friends. But during that first interview on June 6, 2006, there was a lot to ask Bernard because we had never met before, or if we had, it was only briefly. We spoke about his exhibition, The St Peters Suite.

Here we go, starting with Bernard.

Bernard: I’ve titled [the exhibition] The St Peters Suite by virtue of the fact that these paintings were done in this wonderful big studio [the studio he still occupies in St Peters with Wendy Sharpe] and that’s given me an opportunity to put lots of things up at the same time, and you can make comparisons which you can’t do if you’ve got a smaller space. It’s probably helped [the exhibition] to be a little more thematic than it would have been.

We [Bernard and Wendy] moved into the studio approximately four years ago. I never dreamed I would be able to work [in such a big space]. It’s also exciting to bring people in. It’s an empowering thing that people can come in and see lots of work and realise that you’re not just fiddling around the edges — it’s real!

Artwriter: You work a lot in the studio?

I’ve always been very disciplined. I also have the ability which I’ve learned to do over the years to be able to switch on and switch off. In order to keep going as an artist I can’t bring my job home with me. I can put on my favourite classical music and immediately get into a mood where I can pick up the pieces and start working again.

That’s something I think I probably developed. Because if I couldn’t do that it would be out of kilter. For me, in order to be a good director of the art school, I need to be a painter and working on ideas. Everything gives confidence to everything else. It’s the only ying and yang thing. You balance your life. [At this time, Bernard was director of the National Art School, Sydney.]

When you come in to the studio, is it like an oasis?

Yes. I usually switch the mobile phone off and put some music on and in a very short space of time I feel very much at home. Because I’ve got all these works around me I immediately step into their world. [It’s] like Alice Through the Looking Glass — I actually step into the paintings and I’m suddenly confronting and thinking about …. it’s a sort of pictorial world I can enter relatively easily and find solace or stimulus.

I don’t like to be too obvious or literal whenever I paint. I’m not an illustrator. I’ve always wanted to be one step removed. I don’t just want to paint pictures of me and Wendy. So I’ll change my character or my personality or the male or the female role and turn them into other people. I suppose it’s a little bit like the world of theatre where I did some paintings previously to do with masks and changing your personality and stepping on to a stage where you’re actually somebody else. They’re sort of like penultimate moments. They’re open-ended. They are a narrative and allegory of people’s lives and metaphors for things. A lot of them feel like they’re on some sort of stage. The stage can be indoor or outdoor, and sometimes we don’t know which way round it is at all. So I’ve put people in positions which are confronting to them, or they’re just getting on with their lives or they’re standing looking back at us. I’m not an angst painter. I often have people with somewhat more anonymous or pondering faces. I don’t want it to be like ‘I am happy, I am sad or I am angry’. I want the viewer to step in.

This one [he showed me a picture of people in a hotel room], there is a story behind it. I did a drawing when I went to Sri Lanka and the drawing was of this amazing room we were staying in. When we came back, about eight months later, that’s where the tsunami went through. This hotel was a little ground floor place in probably the lowest part of the town. We said, ‘that place wouldn’t exist anymore’. It would have filled up like a sink.

I remember the place and the woman who managed it and all those sorts of things. I came in and I painted that. I did it from the drawing, which was not necessarily a pessimistic drawing. It’s a sort of premonition or a thought. But it’s not important to know that to gain something from the painting.

For you it’s almost like memorialising the people who might have been in the room?

That’s right.

You look down on the room from an odd perspective, as though you were above the actual ceiling fan.

I’ve always been interested in multi viewpoints. I try to turn the ordinary into the extraordinary. I try to put in a number of angles, and I think it just makes it more powerful. It’s a more powerful way of entering into the space than the normal horizon line. I like that idea of being in a number of vantage points, or disappearing off the bottom edge.

Could you tell me about the use of dogs in your work?

Could you tell me about the use of dogs in your work?

I have a slight apprehension of dogs, but like all humans I see them as wonderful creatures and in the ideal world if I wasn’t travelling so much, I’d have a dog. As a child I loved that sort of thing. There was a nasty story where a dog mauled my dog and it only lived a few weeks afterwards and I had about 37 stitches in my hand. The worst thing was this dog was completely mad and just ripped my dog apart. I won’t go into details. I was about 12 or 13. And I came home carrying my little cocker spaniel and I knocked on the door, my hands were bleeding, and my poor mother came to the door and almost fainted. It was a traumatic thing, very traumatic at the time. You know they say dogs can sense fear. Sometimes I’m walking down …. And I’ll just have a déjà vu and I just think I don’t trust it 100 per cent. There’s just that slight thing. But these pictures of dogs are probably a celebration of the way people take dogs out to parks and go places and do things.

All your dog pictures look happy (except perhaps the one at left).

Yes. So I’m not setting out to create that worry or whatever. But I suppose I’m drawn to looking at them and dealing with them.

It’s to do with anger and aggression. I suppose deep down I hate anger and confrontation. I think civilised people should do. But I’ve always walked away from any situations. I’ve always thought the idea of a human hitting another or any of those angry things, I just feel quite sickened by. I suppose I’m instinctively a pacifist on all levels. First and foremost, above all my political things, I describe myself as a pacifist. Dogs are metaphors for different breeds of people and attitudes people have.

The painting of the man and woman dining with a sinister character in the background. And the midnight band painting (at left)?

The painting of the man and woman dining with a sinister character in the background. And the midnight band painting (at left)?

I like that mood, and I like that sense of melanchony or unsure. But the one where the two people sat by the dinner painting. What’s nice is I go on a journey myself when I paint them. They’re not totally worked out. So I had two people sat there at a table and I thought, wouldn’t it be interesting to put them in a very unusual environment? The background now is they’re on the end of a road and there’s this other figure, I don’t know who he is, and he’s walking in and seeing the situation. Within that ménage a trios I’m setting up the situation: should he be having dinner with her? What’s going on? It’s a lonely space, and you assume you could hear the footsteps. You put those ingredients together and depending on your mood could go into any direction whatever. And I change things as I go along. (He might open the eyes of one person, or change their expression.) I had a couple of figures looking through the window but I thought it was adding too much to the set. I genuinely don’t know the answer (to what they all mean.)

If you think of my work as all about humanity and how people interact or don’t interact then you’ve got a situation in which he might be the hero, she might be the villain. It’s a slightly threatening mood, but one might say it’s just a clear still night and the pathway is like a journey from one place to another. There’s a lot of theatre. Most of these paintings are travelling somewhere. They’re going somewhere.

What do you read?

I read quite a lot when I get time. It’s a wide range. There’s no definitive thing. I’m even reading Dickens again. From Dostoevsky to Dickens and The Little Seamstress. I like French cinema because it’s to do with the psychology of people; confrontations or affairs, and guilt, and fear, and other aspects which are deeply laden in all of us and we all try to suppress. I try to play some of those things out.

Were your parents arty?

No, not at all. There were no paintings on the walls and very few books. I really do come from a working class family. Council estate. And I was an only child. My father was a sporting person and he worked at the gas board. My mother cleaned floors. [Going to school, Bernard would walk past the grand Georgian houses and the house where Jane Austen lived, and was fascinated and took it in subliminally.]

What opened art and literature for you?

When I was 10 or 11 years of age I got a record player and everybody was going out and getting The Beatles or The Stones, and I was interested in that, but I was also interested in Tschkaikovsky and Stravinsky. I listened to radio programs and found orchestral music to be a rich source; I found I could listen to it longer and further, whereas (pop tunes were soon boring.) That probably got me into reading books and other things. I left school at 16. I worked for over a year. When I was about 18 and I went to art school, my mum and dad said if you want to do it, do it, and I didn’t know what the end product would be. I went to Cardiff College of Art and I took a big truck and my dad drove the truck and it was full of art, sculpture and all sorts of things, and I remember them saying have you got a folio – and they expected me to have a little thing you open up with five or six pieces of work – and I started opening the truck and friends of mine started pulling things out and they said ‘stop, stop, you’re in, you’re obviously a natural’.

I was working doing post office and different jobs to keep going. But there were grants. Because I was working class you could get a grant so I had just enough and I would work at weekends. I did four years at Cardiff, then I went to the Royal College of Art. There were 800 applications and they took 20, at that wonderful time when people like David Hockney, RB Kitaj and Peter Blake and a lot of really significant artists were there doing a day a week. It was very very exciting and I did 3 years at the RCA. At the end I remember a professor asking what I thought about the course, and I said I wish the course was longer. I just want to keep going. So I’m lucky because I can’t think of doing anything other than making art.

I came to Australia in 1976. I came from London to Darwin in one move. Got a job in Darwin Community College. I did it for a bit of experience. I was 25 and I got a job as a lecturer but I didn’t realise quite what an isolated community it was. And it was only a year after the cyclone and there was hardly anything left standing. I don’t think anybody else applied for it! I stayed in a caravan in a swamp with power cuts all the time and I started to teach art in this isolated community and I thought if I did a good job I would be recognised in other parts of the country, but nothing could be further from the truth. I was in Darwin three or four years, but travelled extensively. Started to show in Sydney and Melbourne. I started to realise that Australia was a very exciting place. I enjoyed very much the lack of snobbery. Being working class was now no longer a handicap.

Next moved to Bendigo, working in the art school at Latrobe Uni and going to Melbourne quite a bit. Came to Sydney in 1996 as head of painting at the National Art School and soon got job as director in 1997. I do enjoy steering the art school in a direction which would be good for this city and country. I feel like a custodian, and it’s a very exciting place to work.

Elizabeth Fortescue, September 11, 2012

| Print article | This entry was posted by Elizabeth Fortescue on September 11, 2012 at 9:58 pm, and is filed under News. Follow any responses to this post through RSS 2.0. You can leave a response or trackback from your own site. |