Richard Goodwin, “Mystic Alien” Interview, Australian Galleries exhibition

Richard Goodwin is a Sydney architect and artist who undertook a fascinating social experiment/art performance in the Sydney CBD one day in October 2010, on which I wrote an article for the Daily Telegraph.

Richard Goodwin is a Sydney architect and artist who undertook a fascinating social experiment/art performance in the Sydney CBD one day in October 2010, on which I wrote an article for the Daily Telegraph.

For this performance, Goodwin dressed up in a white boiler suit adorned with words and phrases such as “mystic alien”, “porosity researcher”, and “friend or foe”. Accompanied by a small posse of assistants who were there to film and photograph him, Goodwin caught a ferry to Circular Quay from where he proceeded to make his way through the city, finishing at Milsons Point railway station via Town Hall station. He also detoured via several office blocks on his circuitous path through the city.

Just why Goodwin would do all this is what my interview with him was about.

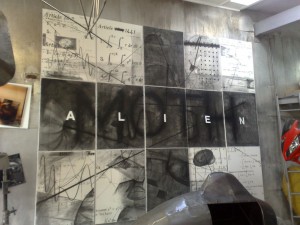

Here is the interview in its entirety, recorded on November 18, 2010, at Goodwin’s Leichhardt studio. This was about a month after the performance/experiment through the city, and we were able to discuss all the things that happened to Goodwin that day.

First, an interesting picture I took [left]. Goodwin’s studio was a fascinating place, occupying the ground floor of the home where he and his family have lived for 22 years. I photographed this helicopter section which is normally attached “parasitically” to the wall of his home. He uses it as a reading room. It had been removed for the time being and will be seen as part of the forthcoming exhibition at Australian Galleries in Sydney, of which the documentation of the Alien performance will be part.

First, an interesting picture I took [left]. Goodwin’s studio was a fascinating place, occupying the ground floor of the home where he and his family have lived for 22 years. I photographed this helicopter section which is normally attached “parasitically” to the wall of his home. He uses it as a reading room. It had been removed for the time being and will be seen as part of the forthcoming exhibition at Australian Galleries in Sydney, of which the documentation of the Alien performance will be part.

Elizabeth Fortescue, November 27, 2010

Richard Goodwin:

All my work, it’s kind of complicated, but just to summarise it, I’m an architect but mostly work as an artist. Over 35 years of practice I’ve come to fuse those back together and become the hybrid. So my work is on three scales: the scale of the gallery as a laboratory, the scale of the city as public art or parasitic transformations of buildings. Now that’s different from an extension on a building because in order to be parasitic and to radically transform, it has to break rules like go higher, go across boundaries, make linkages with other buildings, perhaps. Now cities need radical transformation, and so does public art as a site. Because if we’re going to a) survive b) make architecture more intelligent or give it new technologies or make the social construction of the city better, then we need to radically transform. So the radical nature of my practice is to do with rethinking the city and it rethinks public art because no matter how contextual or supposedly appropriate – although I don’t know that art should be appropriate – public art has become, it still ends up being stuff between buildings. So for me the radical and exciting place for public art is the skin of architecture itself. So the parasitic structure attached like a lot of my work does is where wer’e trying to build. It’s a very difficult area. That leads to the third scale I’m interested in which is the city, the infrastructure scale. So the performances always start my projects and they have since 1975. I’m just putting together a series of images for my exhibition [Between a slum and a hard place, Australian Galleries, Sydney, November 30-December 18, 2010], which summarise those actions between 1975 and 2010, and the Mystic Alien is one of a series of about 12 major performances. At the scale of the gallery, I look at where the body ends and architecture begins, so it’s exoskeleton, so it’s about these machines and the body, but not literal like Stelarc, it’s kind of bicycle and a person, a motor bike and a person, a machine breaking up, what does it say about the body, what does it say about architecture, and you can see various pieces of it. You can take that analogy to a building and say a building’s a body. What prosthetics can we add to make that better? You can take that to the city and say, collecting all these new propositions of structure and pushing them through buildings, monorails and doing all these things to three dimensionalise public space, that’s the third scale. Not many artists work on three scales. Not many would be bothered. It complicates things. But I love working that way. I’m not putting it forward for everyone.

Now the place of performance is very interesting . When I was studying architecture it was form follows function modernism, just before post modernism started. So I wanted to break free from that, and through performance art I was able to be most free. Sort of a direct action to start an idea. And I’ve sort of done that ever since because it was part of the 70s. My research which made me a professor has enabled me to study types of public space inside private space. That’s my theory, it’s called porosity. I believe the more porous a city is the healthier it is. Porous just means the public can get inside more. In the age of terror, everything’s closing down. If all these little spaces inside that we can and should be able to go to – corridors, toilets, foyers and stuff – all start to link up better in the city through parasitic structures, the city’s more complex like an Asian city but I think it’s better, more healthy.

When I was studying these spaces inside buildings as a researcher, end game being ‘how do we make more parasitic public art works?’, I was kind of in disguise. The performances were me in an Armani suit, quite literally, so no one would notice me. It’s so dumb, isn’t it? If you wear an Armani suit you can go anywhere. The Alien is the antithesis. I suppose I’m frustrated by what continues to happen and that movement to change buildings, even for the betterment, is slow. My projects, my actual parasites – one I’m just finishing in Elizabeth Bay – are both public art and private architecture extension. [The one in Elizabeth Bay] took six years to get through council, to get through the Land and Environment Court, so the Alien is a little bit of a frustration. Maybe it’s kind of a self portrait…..

Goodwin wore a real astronaut helmet while dressed as the Mystic Alien.

The space helmet which I found by serendipity in Istanbul , which is really Karpov’s helmet, and that’s been verified and researched, you become an astronaut but you also become a kind of an alien. The performance was really, ‘here’s a guy who’s not going to get in supposedly; I’m just going to go and cause trouble. Walk into offices, walk into buildings. But be absolutely just the other. Passive’. I found it very very interesting. I didn’t get put in jail in the end. All my filmers got stopped, but we still filmed anyway. He [the Alien] has signs on his body of all of these conflicts in us. I put all the names on the suit and Mystic fell above Alien and I thought ‘that’s a Mystic Alien’. It references, as my work has in the past, problems about the alien and all our fears. So he just walked about benignly and it had the most bizarre effect. I didn’t get shut down. People around me [his assistants] did. But equally nobody really approached me. They certainly knew I was there. Everybody was buzzing with ‘what are we going to do, there’s a madman [in the building].’ But it was interesting how wary, strangely wary [people were]. Not even inquisitive. Not really wanting to know. I was so surprised at Town Hall station, because they stopped everyone around me and I was waiting for these hands [to come and grab him on the shoulder]. So the poor little Mystic Alien got on the train and went to Milsons Point.

The helmet’s serious. You could say ‘oh well, it’s someone in fancy dress’. But it definitely wasn’t getting a fancy dress response. It’s as simple as that really. It’s not about the audience. Not that I don’t want it known. Anything that gets the debate deeper. People just don’t get what’s happening in the city.

I said to Goodwin that the ‘parasitic structures’ he referred to reminded me of old cities like Florence, where there was a long tradition of grafting new buildings on to existing buildings.

I said to Goodwin that the ‘parasitic structures’ he referred to reminded me of old cities like Florence, where there was a long tradition of grafting new buildings on to existing buildings.

I often say that everything that I’m on about and I like, happens anyway. The big difference now though is that we’re run out of time, we have to accelerate the process. I’ll give you a good examlpe. We built that lovely Aurora building by Renzo Piano, but we pulled down the State Office Block to build it. It was a bronze clad, award-winning building. Build the Renzo somewhere else. In terms of sustainability, we just can’t keep doing that stuff. It’s a coral reef metaphor. We must keep the armature and radically transform. The aesthetics of radical transformation I think is more up to date – grafting new geometries. Because we now have the power with our computer systems to build all these very complex geometries that can fit in all around this rectilinear texture of the city.

You would probably love mouse runs?

The more complex the better. Again, that’s already modelled. Asia’s already doing it. Shanghai where I often take students is starting to three-dimensionalise its public space. In other words, buildings linking up in the air, roads going higher. Not just one ground plane. Public space should be all through the system, and that’s what makes a city healthy. Public space is like oxygen in a city.

Where did you get on the ferry before alighting at Circular Quay on the day of your Mystic Alien performance?

Balmain. [He went first to Customs House and stood on the under-floor model of the city. He then proceeded on foot to Governor Philip and Macquarie Towers.] I caused a bit of a ruckus there but they didn’t stop me. Even the police saw me there. They were gathering.

Goodwin was escorted out of the Renzo Piano building by security staff, went into another building in Martin Place without being apprehended, then went to the Hilton Hotel in George Street where he actually made his way into the corridor system without any trouble. He made it upstairs and into an office.

I did know the people in the office but they didn’t know I was coming. From there into Town Hall station, through the turnstile, and all the time i was filming out of my helmet. [He bought his ticket from a vending machine.] There were some funny pictures of that. I didn’t have my glasses on, and I had to put my glasses over the visor. Here I am deciding what ticket to buy. (use picture here.)

Goodwin caught the train to Milsons Point station. Two of his assistants were still with him, although one had only a mobile phone to photograph him with. He had started off with five photographers.

At Town Hall [station] they were well and truly packed off and people were getting quite agitated. It was a bit anti-climactic in a way. It just shows when you want to cause some trouble, you don’t. And when you’re completely innocent, wanting just to take a photo of architecture … It’s got completely out of hand. All my students are warned all the time that they mustn’t put this stuff on the internet or utube unless they’ve got ethics approval. What isn’t garbage is that you understand that you’re not able to defame people or concentrate on them. To me public space is sacrosanct. The reason I’m so hard core about it is because it is political. In the end it leads to the sort of possibilities in architecture that I find interesting. In fact my work has just been in the Venice Biennale as part of the Now and When visions of what the city will become. It’s not as if this work is not being taken seriously on one level, and yet we’re not doing it.

This parasitic action is based on research. It’s where the buildings might best be combined. Linkages.

Like the aesthetics of the film Blade Runner?

Totally Blade Runner. Sci fi always sees things first. It’s known that humans do cities very well and if you take care of the social construction, humans live happier in high density. Humans are great termites. They do high density really well. And that’s where the world’s heading if we’re going to survive.

Goodwin said people were briefly happy in suburbia in the 1960s, but that was because their doors were always left open. There wasn’t the same level of personal security observed.

Goodwin said people were briefly happy in suburbia in the 1960s, but that was because their doors were always left open. There wasn’t the same level of personal security observed.

The only way to change suburbia is to open all the doors. Cities is my thing, but art allows me to be more radical with it. And art has a great history in changing history. It’s not public art. Trouble is public art is becoming compliant again. It might be all ‘oh well, it’s contextual and site specific’, but if it’s too polite it’s just window-dressing. I mean, art’s sort of the conscience of the city.

What’s the project in Elizabeth Bay?

The scaffolding is in the process of coming down, so you’ll see it. All of my work appropriates things. Takes junk and makes it something else. Even on a big scale. So this timber thing here [he showed me a model] is a wing roof based on a Stealth bomber and it’s on top of this building. This [structure] shades the thing, collects water to do the gardens, uses ventilators so the air conditioning is not always needed. The carbon footprint of the building is 50 per cent less.

From around, the public do see it [so it could be public art]. It’s not an extension because it’s not allowed. So we’re at this point where the elasticity of urban planning must be made more intelligent. Because the debate about architecture, about public art, is just too dumb.

Copyright Elizabeth Fortescue, 2010

| Print article | This entry was posted by Elizabeth Fortescue on November 27, 2010 at 7:21 pm, and is filed under Uncategorized. Follow any responses to this post through RSS 2.0. You can leave a response or trackback from your own site. |