Yang Zhichao and the Chinese Bible: major new artwork for the Art Gallery of NSW

Yang Zhichao‘s artwork, Chinese Bible, on view at Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation (SCAF) in Sydney until August 1, 2015, is one of the most extraordinary works of contemporary art I have ever seen.

Now it belongs to the Art Gallery of NSW, thanks to its recent gifting by the Sherman family.

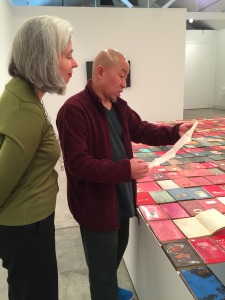

I saw Chinese Bible at SCAF and interviewed the artist with the help of interpreter and Chinese art authority Dr Claire Roberts.

My interview is reproduced below.

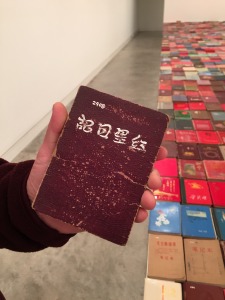

But first, a brief introduction. Chinese Bible, 2009, is a side-by-side display of 3000 personal diaries dating to China in the 50 years between 1949 and 1999. This period includes the years of the Cultural Revolution of 1966 to 1976.

“Private reflections were inherently dangerous in China during this period, with some decades more dangerous than others,” Gene Sherman writes in the Chinese Bible catalogue.

“As we know, the country focused exclusively on the collective at the expense of the individual.”

So, without further ado, here is my interview with Yang Zhichao.

Elizabeth Fortescue: What is the significance of these diaries and notebooks? Each one feels to me like a very important piece of history.

Yang Zhichao: There’s an important place in history for every diary that’s here, because of its connection to the individual and the individual’s connection to what was happening in China.

Were these ordinary, everyday people?

Yes.

Is it normal in China to carry a notebook around with you?

For some of these periods, the Cultural Revolution in particular, people were required to record things. You were required by your superiors in your work unit to carry your notebook.

At all times, or just at work?

Mainly at work, because from the 1950s onwards there were so many meetings. And they were meetings to disseminate politics and the directives from the Communist Party central committee. So writing down these directives was an important part of life. So that was a responsibility you had in the system.

Did people buy the notebooks, or were they distributed by authorities?

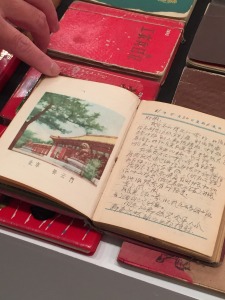

There are two instances. There’s the instance where the diaries were given out to people in the work unit as part of that expectation. But also people could buy them from shops. Of course in addition to writing down what was expected of them, people would make their own notations and carry these notebooks around so you do find a lot of different kinds of records in them, some of which reflect personal feelings or experiences.

You could be asked to reveal the contents of your notebook to your superiors?

During the early years of the Cultural Revolution in particular, people were required to offer up their diaries for superiors to look at.

This custom is no longer required?

This custom is no longer required?

No. By the early 1970s this kind of practice really had petered out. With the exception of people who had committed political errors in the eyes of the party. There was a continuing expectation that they would write self criticisms. Or that they would be forced to write confessions.

Did your parents have to keep notebooks like these?

Yes. Either they would carry it around or it would be in the drawer of their desk and they would use it as necessary.

Did people write little expressions of self that possibly they needed to disguise not to get into trouble?

The personal notations are very different from what we would think of as personal diary entries. What was regarded as a personal notation might have been something quite ordinary rather than a revealing diary quote.

I have been told that the recording of a little recipe might be seen as going against the regime?

The crucial thing is when that recipe was written — if it was in the middle of a major political campaign during the Cultural Revolution, and you were supposed to be recording political things and when you showed your diary for inspection it’s revealed that you’re thinking about (cooking), then your mind was not on the job. So you would have an ideological problem.

How do you think they all ended up in the markets for you to collect?

In Beijing in particular, where I collected most of the diaries, people value the written word and diary keeping. There’s an old custom in China that when you have items that you no longer need, you get rid of them. There are lots of people who go through unwanted things. These people come around all the time and they sort the different household waste into different categories and there’s a whole chain. Things then get funnelled into different avenues for resale or changing hands. And often a very small amount of money changes hands. It might be $1 or 20 cents. But for people living hard lives, it all adds up.

Is that what each of these diaries cost?

Sometimes things are just thrown out into the street, so people have just decided they want to dump stuff so there’s no direct monetary exchange. Someone just sees what’s there and goes through it. Basically these are valued for their paper so they’re sold according to their weight.

I interviewed Song Dong about his work at Carriageworks. Your work seems to resonate with Song Dong’s installation.

Song Dong’s mother is quite unusual in that she never threw anything away, but 90 per cent of Chinese households are continually getting rid of stuff they no longer need.

How much did you pay for the diaries?

The collection was put together 2005-2008. To begin with when I first discovered these notebooks they were very cheap. There were other people who might come to the markets and they might buy one. They might like the design of the cover. But no one was collecting them in a large scale until I expressed interest. Over time the traders got smart, so a notebook that had no content would be cheaper whereas one with notes in would be more expensive. Condition was another factor in deciding the price, and also size. So over the course of the three years I would have spent less than $10,000 Australian buying the diaries. Towards the end, if there was a particularly good diary, or now, a dealer might be wanting a couple of hundred for a diary because they’re sought after.

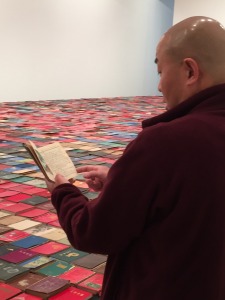

Have you read all the diaries yourself?

No, there are too many. But I’ve handled each one and looked through them all. I’ve read many of them but I couldn’t say I’ve read them all cover to cover.

Do you still collect these types of diaries?

I’m still very interested in diaries. If I come across particularly interesting diaries I will collect them, but this work is now complete.

It’s wonderful to have a work like this in Sydney.

To be perfectly frank, this material was all in second-hand markets. It’s not really taken that seriously in China. In a place like Australia it can be appreciated and studied.

Elizabeth Fortescue, July 8, 2015

| Print article | This entry was posted by Elizabeth Fortescue on July 8, 2015 at 11:09 pm, and is filed under News. Follow any responses to this post through RSS 2.0. You can leave a response or trackback from your own site. |