Archive for May, 2014

Erika Diettes: images of suffering go on view in Head On Photo Festival

May 16th

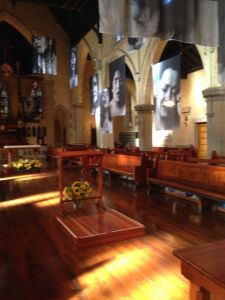

Erika Diettes’ photographic portraits of Colombian women are printed on lengths of fine silk. Numbering about 20, the portraits are delicately suspended from the ceiling of St Canice’s church in Elizabeth Bay, Sydney, as part of the Head On Photo Festival.

The peaceful interior of St Canice’s is a perfect setting for these extraordinary images of real-life suffering, of faces that call to mind the women in Renaissance paintings of the entombment of Christ.

The women in Diettes’ photographs had also endured suffering of Biblical proportions, having been forced to witness their loved ones tortured and executed during the armed terror which has beset Colombia throughout decades of armed conflict.

One of the women was made to watch as her mother’s tongue was cut out and her eyes gouged out. Another woman scooped up and drank her murdered husband’s blood in an irrational bid to absorb his life force into her own body. Another had been raped by six men but had suppressed her screams for the sake of her children who were locked in the next room.

Diettes photographed all these women as they related their stories of pain and death. During each interview, there inevitably there came a moment when words could not describe the women’s pain. That was the moment, almost transcendental in its intensity, that Diettes pressed the shutter button on her camera.

“I had the particular intention of photographing them in the moment that their eyes closed, because they are present in the exact moment of the memory of that killing,” she said.

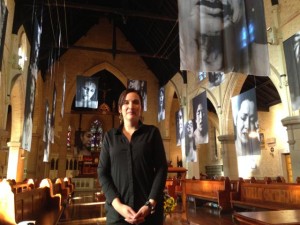

I met Diettes at St Canice’s this week, finding her to be younger than I had expected. Her manner was warm and open. She talked about why she had titled the series of photographs Sudarios, meaning “shrouds” in Spanish.

“The basic connection for me was the holy shroud of Turin which is supposed to be the last time Jesus’s face is supposed to have left a physical impression on the fabric,” Diettes said.

“That’s my intention with printing it on silk. This would be the last impression of these women while alive.”

Even though the women lived, there was a part of them that died.

“I have been working with victims of violence for quite some time now,” Diettes said. “Many family members of the disappeared or that have had somebody killed, they always say after the encounter with violence ‘it’s like you are left dead but you are still alive’.”

Diettes sat with each of her subjects for two or three hours. A therapist was also present as the women told their stories, often for the very first time.

The series was shot in 2010 and 2011.

“All these women were from a region called Antioquia. Medellin is the capital,” Diettes said. “I took the images in rural areas of Antioquia in a place very historically hit by the guerrilla and paramilitary violence [as well as land disputes and the drug trade].”

It shows the level of trust the women had in Diettes that they agreed to be photographed with bare shoulders. One of the first portraits in the series was of a woman in a flowery shirt. Diettes thought the shirt was distracting. She asked the women to keep their jewellery and makeup on, however, as symbols of their dignity in the face of terrible adversity.

Diettes has not displayed the women’s stories alongside the photographs in the exhibition. To do so, she felt, would be to connect the stories too closely to the individual women. The sad fact is that Colombia is not the only place where such atrocities occur. They happen all over the world.

Elizabeth Fortescue, May 16, 2014